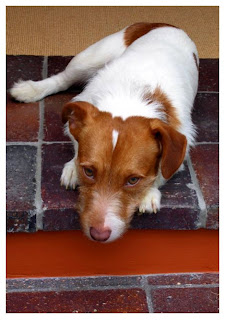

Well, this is our new companion. Earlier today, we picked him up from a farm in South Wales where he had been in foster care after his original keepers (a family falling apart) had handed him over to a charity. I decided to call him Montague, or Monty, after Monty Woolley and his radio character, the Magnificent Montague—irascible, swellheaded, and hopelessly demoted. Now, “Montague” used to be my nom de blog as well; so, I’m only passing it on to the little one now resting next to me.

Will Montague grow into his name? Will he defy it or make it his own, after having been confronted, pell mell, with such an appellation? As yet, he barely responds when thus addressed. After all, until a few hours ago, he used to go by another name.

The act of naming and the meaning of names, the study of which is called onomastics (since every field of scholarly investigation must have a title validating it as such), has always fascinated me. As a child, I sensed naming to be a decided gesture of ownership, an announcement of having brought into being—that is, brought into my life—something that, before I laid claim to it thus definitively, had been vague, obscure or utterly unknown to me. After I had named the toys in my room, I began to name the fictional characters I drew or wrote about. Could I make up my own life in this arbitrary, willful way, despite being stuck with a name for life? Somehow, I thought the answer must be a resounding “no.” I had already been claimed by others.

My interest in names and naming only intensified when I read the works of Charles Dickens, who had a knack for the game of the name: proper nouns that might not be proper at all, but that keep you wondering, that arouse your suspicion, that conjure up a face in a few syllables. In an essay on the subject, I called this quality in Dickens “Onomancy”—the act of conjuring up the spirit of a character by virtue of a moniker. It is a game in which the reader is invited to guess whether nomen truly is omen.

In Dickens’s Little Dorrit, for instance, you will encounter a rich assortment of suggestive surnames, such as Plornish, Flintwinch, or Stiltstalking, and sobriquets such as Pet, Tip, or Altro. It has its mispronounced names (Biraud for Rigaud, Cavallooro for Cavalletto) and its unpronounced names (A. B., P. Q., and X. Y.). It has its aptonyms (Messrs. Peddle and Pool, solicitors) and eponyms (Barnacleism); its cognominal chameleon (Rigaud, alias Blandois, alias Lagnier) and its renamed renegade (Harriet Beadle, alias Hattey, alias Tattycoram); its allegoric Everyman (Bishop, Bar, or Bench) and its Nobody. After all, it is a story about losing and regaining a reputation—a story of how to make a name a good one.

In old-time radio drama, names were rarely quite this fanciful—but they were called out and repeated far more often than in everyday life. The creators of such plays assumed, and wrongly—that names, heard only once, would not sink in; that it would be confusing for the listener to discern just who was talking to whom. To be sure, some producers, like the Hummerts, went rather too far with such designations; but perhaps this is why Mr. Keen, Tracer of Lost Persons, managed to make such a name for himself, despite the fact that he was dull as . . . , well, let’s not start with the name calling.

As tempting as it might be, there won’t be any mention of names in the radio play I am currently imagining. The listener will have to distinguish between no more than two main characters, individuals who are nothing to one another. Their personalities won’t be pronounced by mere proper nouns; instead, they have to speak for themselves. That is, I have to put words into their mouths first—if Montague, wild and woolly, will permit me to divert my attention. The named one, you see, has already laid claim to me.

He is very adorable.I rather like Woolly Monty. Sounds sort of elephantine, though. :~)

LikeLike

Well, then I can only hope he does not live up to his name. After just a few short hours, he is beginning to respond to it, though.

LikeLike

Monty looks like a fine dog. Maybe he\’ll be able to chip in with some sound effects on your radio production ;-)In many of my stories I selected character names with some sort of reference, possibly subtle, to the content of the story. But mainly I selected names for their sound and how they alliterated/flowed with the rest of the sentence(s).

LikeLike

That\’d be nice, if on cue. So far, the only sound he\’s uttered has been a yawn.Telling names are probably most effective in allegory and satire. In my attempts at realist fiction, I have often made the mistake of starting with a name–and then relying too much on it to give its bearer a chance to become complex. My characters were obliged to enact their names and, as a result, became human in name only.

LikeLike

There\’s something to that – I do tend to concentrate on allegories/satires. The name I like best is \”Heinrich Holzschnitt\”, for a psychologist in a satirical piece, as a wink to Woody Allen and his psychoanlyst in \”Conversations with Helmholtz\”Often I change the name I used in a story at the last minute.I looked in several directories and name registers for Germany, Austria and Switzerland, and there\’s absolutely nobody with this surname, yet I think it sounds like a valid German name to the uninitiated.

LikeLike

What a name! What a life! I suspect Holzschnitt might have been the mastermind behind IKEA.

LikeLike