It doesn’t happen often that, after watching a 21-century movie based on a 21-century novel, I walk straight into the nearest bookstore to get my hands on a shiny paperback copy of the original, the initial publication of which escaped me as a matter of course. Come to think of it, this never happened before; and that it did happen in the case of Me and Orson Welles has a lot to do with the fact that the film is concerned with the 1930s, with New York City, and with that wunderkind from Wisconsin, the most lionized exponent of American radio drama, into which by now dried up wellspring of entertainment, commerce and propaganda it permits us a rare peek. You might say that I was the target audience for Richard Linklater’s comedy, which goes a long way in explaining its lack of success at the box office.

And yet, despite the film’s considerable enticements—among them its scrupulous attention to verisimilitudinous detail and a nonchalant disregard for those moviegoers who, having been drawn in by Zac Efron, draw a blank whenever references to, say, Les Tremayne or The Columbia Workshop are being tossed into their popcorn littered laps—it wasn’t my fondness for the subject matter, much less the richness of the material, that convinced me to pick up Robert Kaplow’s novel, first published in 2003. Indeed, it was the glossiness of the treatment that left me with the impression that something had gotten lost or left behind in the process of adaptation—and I was curious to discover what that might be.

On the face of it, the movie is as faithful to the novel as the book is to the history and culture on which it draws. Much of the dialogue is lifted verbatim from the page, even though the decision not to let the protagonist remain the teller of his own tale constitutes a significant shift in perspective as we now get to experience the events alongside the young man rather than through his mind’s eye. In one trailer for the film, the voice-over narration is retained, suggesting how much more intimate and intricate this story could have been—and indeed is in print—and how emotionally uninvolving the adaptation has turned out to be.

Without Samuels’s narration and with a scene-stealing performance by Christian McKay as Welles, the screen version gives the unguarded protégé, portrayed by the comparatively bland Efron, rather less of a chance to have the final word and to claim center stage, as the sly title suggests, by putting himself first.

The question at the heart of the story, on page and screen alike, is whether successes and failures are born or made. Prominence or obscurity, life or death, are not so much determined by individual talent, the story drives home, but by the circumstances and relationships in which that talent can or cannot manifest itself. We know Welles is a phony when he goes around giving the same spiel to each member of the cast who is about to crack up and endanger the opening of the show, insisting that they are “God-created.” They are, if anything, Welles-created or Welles-undone.

Finding this out the hard way—however easy it may have looked initially—is high school student Richard Samuels who, stumbling onto the scene quite by accicent, becomes a minor player in a major theatrical production of a Shakespearean drama directed by a very young, and very determined, Orson Welles. Samuels’s fortunes are made and lost within a single week, at the end of which his name is stricken from the playbill and his life reconsigned to inconspicuity, all on account of that towering ego of the Mercury.

The premise is an intriguing one: a forgotten man who lives to tell how and why he did matter, after all—a handsome stand-in for all of us who blew it at some crucial stage in our lives and careers. Shrewdly concealing that it was he who nearly ruined the Mercury during dress rehearsal by setting off the sprinklers, Samuels can luxuriate in the belief that he may have inadvertently saved the production by reassuring a superstitious Welles that opening night would run smoothly.

Speculating about the personalities and motives of historical figures, dramas based on true events often insert an imaginary proxy or guide into the scene of the action, a marginal figure through or with whom the audience experiences a past it is invited to assume otherwise real. And given that Me and Orson Welles goes to considerable length capturing the goings-on at the Mercury Theater, anno 1937, I was quite willing to make that assumption. Hey, even Joe Cotten looks remarkably like Joseph Cotten (without the charisma, mind).

It was not until I read the novel that I realized that Kaplow and the screenwriters, while ostensibly drawing their figures from life, attributed individual traits and behaviors to different real-life personages. Whereas actor George Coulouris is having opening night jitters on screen, it was the lesser-known Joseph Holland who experienced same in the novel.

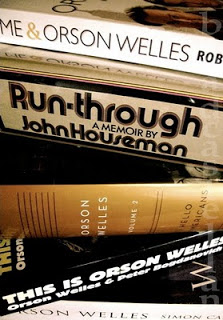

Although quite willing to let bygones be fiction, I consulted Mercury producer John Houseman’s memoir Run-through, which suggests that the apprehensive one was indeed Coulouris. Houseman’s recollections also reveal that the fictional character of Samuels was based in part on young Arthur Anderson, a regular on radio’s Let’s Pretend program who, like Samuels, played the role of Lucius in the Mercury production. According to Houseman, it was Anderson who flooded the theater by conducting experiments with the sprinkler valves.

Never mind irrigation; I was trying to arrive at the source of my irritation, which, plainly put, is this: Why research so thoroughly to so little avail? Why be content to present a slight drama peopled with folks whose names, though no longer on the tip of everyone’s tongue, can be found in the annals of film and theater? The missed opportunity—an opportunity that Welles certainly seized—of becoming culturally and politically relevant makes itself felt in the character of Sam Leve, the Mercury’s set designer—a forgotten character reconsidered in the novel but neglected anew in the screenplay.

Anderson’s contributions aside, it is to Leve’s account of the Mercury’s Julius Caesar that Kaplow was indebted, a debt he acknowledges in the “Special thanks” preceding the narrative he fashioned from it.

“[P]oor downtrodden Sam Leve”—as Simon Callow calls him rather patronizingly in his biography of Orson Welles—was very nearly denied credit for his work on the set. Featuring prominently in the novel, he is partially vindicated by being given one of the novel’s most poignant speeches, a speech that turns Me and Orson Welles into something larger and grander than an intriguing if inconsequential speculation about a brilliant, egomaniacal boy wonder.

Confiding in Leve, with whom he has no such exchange in the movie, Samuels calls Welles a “kind of monster,” to which Leve replies: “We live in a world where monsters get their faces on the covers of the magazines.” In this exchange is expressed what might—and, I believe, should—have been the crux of the screen version: the story of a “kind of monster,” a man who professes to turn Julius Caesar into an indictment of fascism, however conceptually flawed (as Callow points out), but who, in his dictatorial stance, refuses to acknowledge Leve’s contributions in the credits of the playbill and shows no qualms in replacing Samuels when the latter begins to assert himself.

“As in the synagogue we sing the praises of God,” Leve philosophizes in the speech that did not make it into the screenplay, “so in the theatre we sing the dignity of man.” Without becoming overly didactic or metaphorical, Me and Orson Welles, the motion picture, could have put its authenticity to greater, more dignified purpose by not obscuring or trivializing history, by reminding us that Jews like Leve and Samuels were fighting for recognition as the Jewish people of Europe were facing annihilation.

To some degree, the glossy, rather more Gentile film version is complicit in the effacement of Jewish culture by homogenizing the story, by removing the Jewish references and Yiddish expressions that distinguish Kaplow’s novel. Instead of erasing the historical subtext, the film might have encouraged us to see the Mercury’s troubled production of Julius Caesar as an ambitious if somewhat ambiguous and perhaps disingenuous reading of the signs of the times, thereby making us consider the role and responsibility of the performing arts—including films like Me and Orson Welles—in the shaping of history and of our understanding of it.

Related writings

“On This Day in 1938: The Mercury Players ‘dismember Caesar’”

“On This Day in 1937: The Shadow Gets a Voice-over”

You and Gene Autry. Right where you belong, back in the saddle again. I await your horsing around with that.

LikeLike

Interesting. I find it the most frustrating thing with adaptations of novels when the characters are mismatched with their character. It even annoyed me with the television dramatization of Louis Lamour's The Sacketts. But it is evidence, and I imagine Orson Welles would agree, that a story broadcast is a different story than the written one.

LikeLike

The old hobbyhorse is not in the knacker’s yard yet, Clifton. Just a little slower these days.

LikeLike

I don’t even mind so much when a screen version is a “different story than the written one,” Doug. It’s when the original is a lived story being rewritten as fiction that I tend to become more critical.

LikeLike

Huh. Saw you at Doug's, decided to check you out. Good stuff.(Do NOT bother reading my blog. I'm dead serious. I have it only to comment on other blogs.)

LikeLike

I've seen you there. Thanks for stopping by. The \”St. David\” reference was kind of an in joke, inspired—if that's the word—by what Doug told me in his comments on a previous post.

LikeLike

Harry, that's an important difference I hadn't thought about. Fair enough. Nice to see you, TLP.

LikeLike

Harry, Arthur Anderson himself told a number of us at a radio convention that he was indeed the person who accidentally set off the sprinklers on the set of \”Julius Caesar.\” Anderson has an autobiography that just was published and while I haven't read it, according to some of his interviews, I believe, he touches upon same.By the way, thanks for touching on this. I read the book when it was first published and though flawed, enjoyed the film as well, but the book is definitely superior as one would hope.

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing, Jim. You know, it felt good to return to what is still my favorite subject.

LikeLike