(Im)memorabilia: Radio Ties/Wireless Networks

Radio carries us into the world at the turn of a dial. On the dial of this British receiver, ‘Welsh’ takes a central position. It would have resonated with listeners who speak Welsh in their homes. The 1947 Ever Ready Model C/A is an early portable set. It allowed listeners to venture out and take that world of sound along with them.

After leaving Manhattan in 2004, I struggled to find myself in rural Wales. I feared that nothing I knew and felt eager to share could be of value to anyone here. Living in a remote cottage, I retreated into a private world. It is the need to open myself up that compelled me to stage (Im)memorabilia.

The radio is on loan from the Ceredigion Museum in Aberystwyth. By making it part of this exhibition, I am drawing on connections that I had long failed to see.

Radio Books

These books speak volumes about values. They show that radio once enjoyed a central role in Western culture. They also remind us that it required tangible media to turn ephemeral broadcasts into events worth preserving.

In 1940s America, plays were taken in free of charge by tens of millions of radio listeners. Only one of those performances, Norman Corwin’s On a Note of Triumph (1945), achieved the status of national bestseller. A commentary on V-J (Victory in Japan) Day, it was also issued as a record album. The following year, Frederic Wakeman’s The Hucksters (1946), a novel-turned-motion picture, became a massive commercial success by declaring the radio industry creatively bankrupt.

US radio was accused of being too commercial; but, sound being immaterial, radio was also not commercial enough. Must words become products before they can matter? Today, the force of this bias is felt by anyone sharing ideas freely online.

Some of the books shown below were featured in (Im)memorabilia, an exhibition of ephemera and neglected collectibles. (Im)memorabilia was on show at the School of Art galleries, Aberystwyth University, from 1 December 2014 to 6 February 2015.

Wireless Connections: Neil Brand

Moving from the US to Britain in 2004, I was surprised to discover that radio plays are still produced regularly here. When I asked him about his experience in radio, British playwright and composer Neil Brand replied:

Radio allows the greatest scope for my ambitions as a dramatist and composer. For the radio, I can write movies that unspool in my head and hear them realised by top-class actors. The resulting images are pitch perfect because listeners craft them in their own heads.

The experience of listening is equal to, and sometimes more profound than, the intensity of theatre or cinema. Christmas Carol, my most recent radio adaptation, is a case in point. Although mounted as a live concert for a studio audience, it is written for home listeners who are free to visualise the interior drama.

Sightless radio and soundless film leave a blank page on which to practise my craft. The most satisfying aspect of working in these low-budget, specialist media is the comparative lack of editorial governance. They are a perfect arena in which to realise a singular vision.

Wireless Connections: Clif Martin

Listening, like writing, is a solitary experience. Working on, Immaterial Culture, my radio study and collecting recordings to write about, I spent much time by myself. I came to realise that the reason I listen, write and catalogue my collections is to be alone. Still, like anyone with specialist interests, I meet others who share my enthusiasms. One of them, Clif Martin, worked in the industry I know only second hand. Asked about his radio days, he replied:

I was born in 1930 near Detroit, Michigan, where The Lone Ranger radio program was produced and broadcast. I grew up loving radio when it was the major home entertainment medium. In 1950, I started working as a disk jockey. By then, network radio was being replaced by local broadcasting.

The first station I worked at was WMRP in Flint, Michigan. We enjoyed great creative freedom. We were stars. I am privileged to have experienced radio as a listener, fan and performer. Not for a moment do I wish I were younger.

Wireless Connections: Claudia Williams

Relocating from Germany to the US and then to Wales, I had to learn to let go of many things I owned. Now I travel with the immaterial artefacts that matter to me. There are some 30,000 sound recordings on my laptop. They range from historic broadcasts to ambient sounds and voices of friends.

Before the commercial use of recording devices made their collection possible, sounds could only be recollected. Indeed, they keep reverberating. Painter Claudia Williams, whose life I researched for An Intimate Acquaintance, a monograph on her, recalled recently:

My husband [artist Gwilym Prichard] and I have vivid memories of Children’s Hour from about 1940 onwards or maybe a year or two before that. Heard regularly on the programme were Freddie Grisewood and Derek McCulloch. McCulloch signed off saying ‘Goodnight, children everywhere, goodnight’ in a very comforting voice. I remember Larry the Lamb baaing ‘Mr Mayor, Sir.’

And then there were the voices of Alvar Lidell and Stuart Hibberd conveying wartime news.

Wireless Connections: Danny Fortune

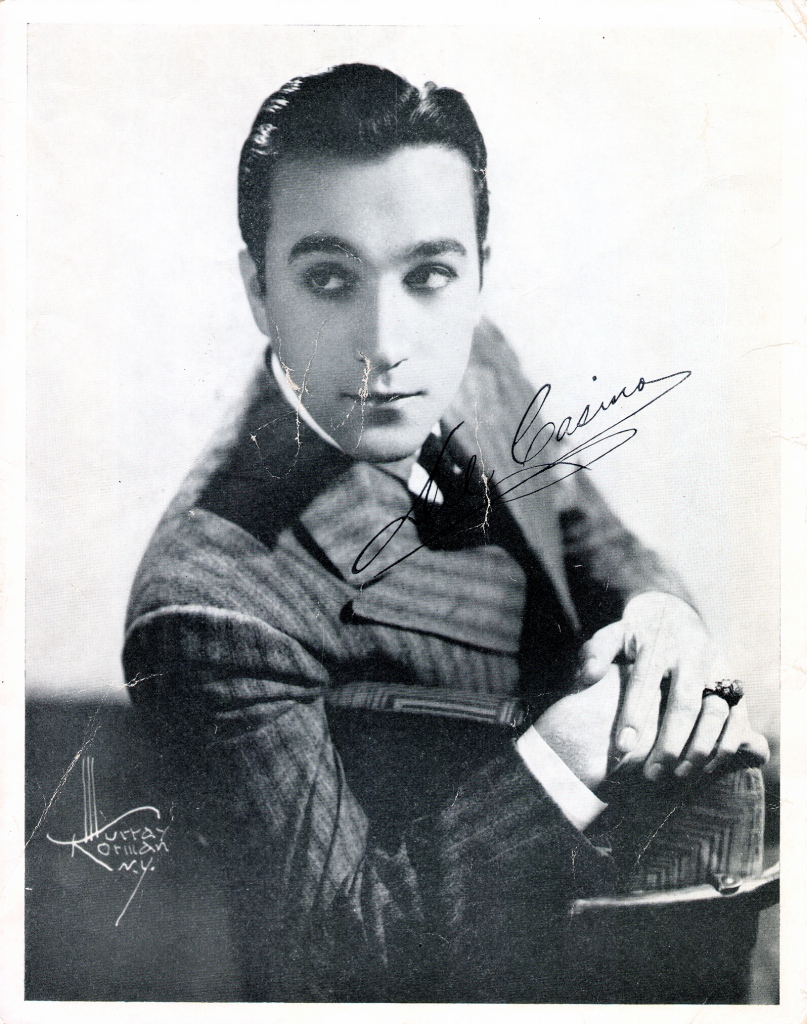

Years ago, while I was gathering material for a doctoral study on American radio, these photographs were given to me by my friend, the film historian Danny Fortune. Many of them bear the inscription “To Hazel.” When asked about that, Danny replied:

My mother, Hazel Richards, started collecting memorabilia as a young girl, from the 1930s to 1940s.

She told me that she would write to the stars and ask for their autographs. By the time I happened along, radio was giving way to television. But my mother kept faithfully listening to radio shows. When we did watch television together, she always pointed out which performers she remembered from the radio days. For instance, she told me that Rose Marie from The Dick Van Dyke Show was once Baby Rose Marie, a child singer with a gruff voice.

This collection brings back pleasant memories of the woman who gave me my first nostalgic notions. It now belongs to the world.

Radio Montage

This is an excerpt of an evolving sound montage of American and British radio recordings from my archive, which was playing in the gallery during the run of (Im)memorabilia. To go through my archive in its entirety would take over 480 days of nonstop listening.

At the time of the exhibition opening, the montage consisted of the following recordings:

- Gracie Fields introduces her song “I Love the Moon” (2 seconds; UK, 1930s)

- Rudy Vallee performs a potpourri of tunes from the motion picture My Lucky Star (USA, 25 August 1938)

- US Presidential Press Secretary Eben A. Ayers announces of the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima (USA, 6 August 1945)

- Rudy Vallee closes his NBC variety programme (USA, 25 August 1938)

- Agnes Moorehead performs in a scene from the radio play Sorry, Wrong Number (USA, 25 May 1943)

- Smilin’ Ed McConnell sings “Say It Again” (USA, 1940s)

- Bing Crosby and Claudette Colbert sing “La vie en rose” on Crosby’s variety programme (USA, 25 October 1950)

- William Conrad announces the thriller programme Escape (USA, 23 June 1950

- Bandleader Kay Kyser performs on the Treasure Star Parade programme(USA, c. 1942)

- Alvar Lidell reads the BBC news (UK, 15 September 1940); Wizard of Oz radio debuts on the Good Newsprogramme (USA, 29 June 1939)

- Tallulah Bankhead welcomes listeners to her Big Show programme (USA, 3 December 1950)

- Meredith Willson performs his novelty tune “This Is It” on the Big Show programme (USA, 3 December 1950)

- Edward Arnold announces Claudette Colbert as guest star on the Good News programme (USA, 1 February 1940)

- Introduction to the thriller programme Lights Out (USA, 9 February 1943)

- Billy Mayerl performs “Green Tulips” (UK, 1935)

- Tallulah Bankhead is interviewed by Mary Margaret McBride (USA, c. 1950)

- The Western Brothers perform on the programme Transatlantic Call (USA/UK, 1 October 1944)

- Claudette Colbert introduces herself in a UNICEF broadcast on the subjects of Yaws in Indonesia (UN Radio, 1958)

- Bing Crosby performs “I’m a Cranky Old Yank in a Clanky Old Tank” (USA, 1944)

- Connie Boswell sings “Lilacs in the Rain” (USA, 28 December 1939)

- Introduction to “The Death Triangle,” an episode of the thriller programme The Shadow (USA, 12 December 1937)

- Paul Specht and His Orchestra perform on the Radio and Television Institute Revue programme (USA, 1931)

- A Welsh cast including Ivor Novello perform in the play “Choir Practice: A Storm in a Welsh Teacup” (UK, 1946)

- Bing Crosby sings “Sunday, Monday, or Always” and “She’s from Missouri” from the film Dixie on the Lux Radio Theater (USA, 20 December 1943)

- A portrait of Wales as heard on the American programme Ports of Call (USA, c. 1935)

- Dean Martin performs “Three Wishes” on the Martin and Lewis programme (USA, 15 May 1949)

- Judy Garland sings “A Pretty Girl Milking Her Cow” (USA, 30 October 1952)

- An excerpt from the serial Myrt and Marge (USA, 1946)

- Bob Hope and Doris Day performing “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” (USA, 11 October 1949)

- Art Baker’s Notebook (USA, 1940s); scenes from Girl Crazy as performed on the Ford Theater programme (USA, 1950s)

- Columbia Broadcasting System newsreader attempts to call Honolulu after the attack on Pearl Harbor (USA, 7 December 1941)

- German propaganda broadcast (Germany, 27 February 1940)