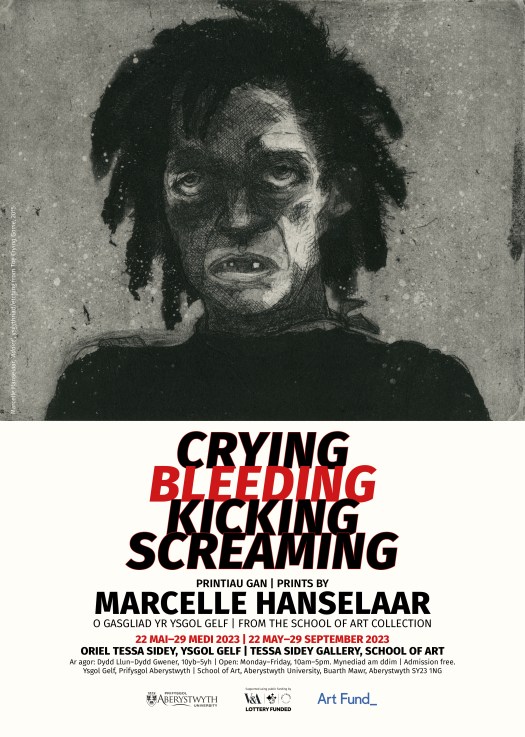

“I love it when curators come up with juicy titles.” That is how London-based painter-printmaker Marcelle Hanselaar announced the exhibition Crying Bleeding Kicking Screaming in one of her newsletters.

As Hanselaar put it, a title like that offers a “glimpse” of how others read her work and “how it might impact the viewer.” It is “part preparation and part enticement to what will be shown and the very least it will do is to put visitors in a state of mind of curiosity.”

Hanselaar’s prints – and their titles – do just that: they make us curious, and they play on our inquisitiveness. They do not necessarily show and tell us what we want to see, but they remind us that we are eager and anxious to look. Providing another chance to view works in public, an exhibition can and should also facilitate the act of looking.

The latest in a series of projects that I, assisted by the School of Art’s Senior curator Neil Holland, have carried out annually since 2013 with undergraduate students of my curating module at Aberystwyth University, Crying Bleeding Kicking Screaming conflates the titles of two of Hanselaar’s print portfolios: We’re all bleeding (2012) and The Crying Game (2015/17).

Determining on a title well in advance, before a narrative has been finalised through display, is always challenging. Repeating Hanselaar’s words while adding to them was meant to signal that curators serve as editors, not as writers: at best, we help to bring intended meanings across. Providing context for the visual language, we should aim to avoid overwriting by superimposing meanings or substituting word for image.

“Whenever I get a request to write something about my work,” Hanselaar wrote in the catalogue for her first solo exhibition at the School of Art back in 2008, “my first response is: are my images not sufficient?” Indeed, most of Hanselaar’s works are so direct, they do not seem to require – or benefit from – gallery interpretation. What can curators add to works that speak for themselves?

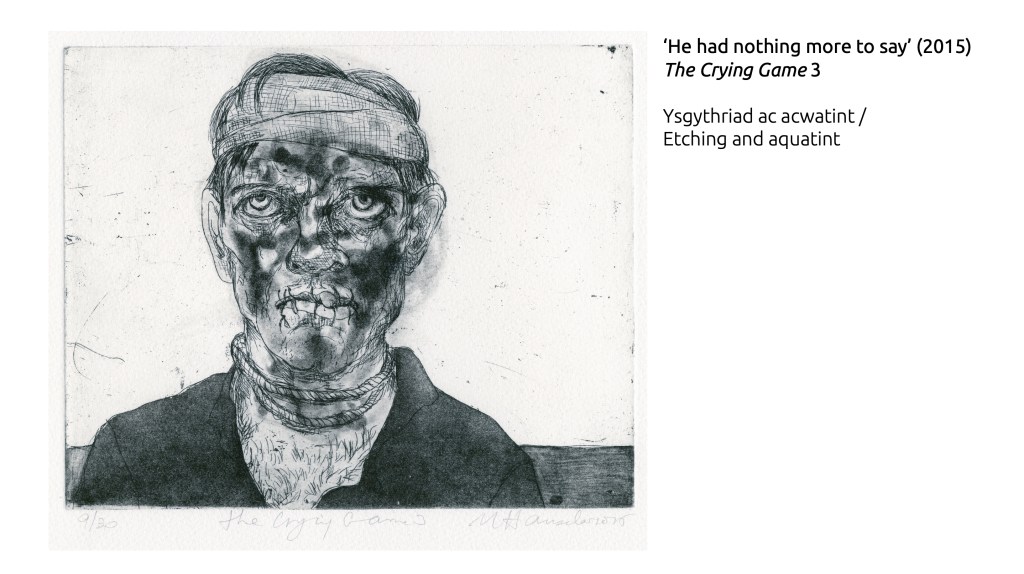

Responding to this question, the introductory panel quotes one of the titles of Hanselaar’s prints from The Crying Game: “He had nothing more to say.” The etching – an imaginary, metaphoric close-up of human suffering showing a wounded man whose mouth is sewn up – is one of the first prints that visitors to the exhibition get to see.

Produced in two parts (2015 and 2017), the drama of the thirty prints comprising The Crying Game unfolds episodically and cinematically, telling multiple stories. The title of that portfolio is, not coincidentally, borrowed from the movies. Set in Northern Ireland, the award-winning 1992 thriller The Crying Game tells the fictional stories of individuals affected by the Troubles.

Hanselaar’s close-ups and theatrically staged scenes are similarly focussed on imaginary characters in real-life situations. Action scenes showing moments of violent crises are contrasted with portraits contemplating the impact and aftermath. Among them, a woman’s face, scarred after an acid attack.

Rather than rewriting or transcribing Hanselaar’s visual narratives, Crying Bleeding Kicking Screaming edits – and cuts – to consider new ways of experiencing them. Through groupings of selections from both series, the exhibition aims to foreground recurring themes in Hanselaar’s work:

The secret and the public. The violence of human nature and the violation of human rights. The frailty of civilisation and the loss – or myth – of innocence.

Meanwhile, the complete series in the School of Art collections are presented in chronological order as a digital slide show.

Speaking loudly, Hanselaar’s prints address what is often left unsaid. They give utterance to the horrors experienced by the voiceless and draw attention to acts of silencing. They invite a dialogue about the human condition without claiming the last word.

Knife crime and domestic violence. Migrant crisis and sex trafficking. Local or global, the stories told in The Crying Game are drawn from the headlines. Being “bombarded” by reports of human conflict, Hanselaar asks: “how I would behave if I’d found myself in such circumstances?”

Hanselaar envisions and visualizes scenarios she has not experienced. She shares Picasso’s belief that everything we imagine is real. The “perspective of being one step removed” enables us to take in “what is happening” without “drowning” in the horror of an evolving situation. Some of the titles Hanselaar gives her prints – “Stuck” and “Between a Rock and a Hard Place” among them – communicate this sense of being witness to events in the moment of their unravelling, of momentousness that should give us pause.

Painstaking and incisive, Hanselaar combines the bitten lines of etching with what she calls the “poetry of aquatint” to imagine lived experiences. Most of Hanselaar’s Crying Game prints feature women and children as casualties of acts and actions by men whose “calculations,” as she puts it in another one of her titles “were all wrong.”

In “times of social upheaval,” Hanselaar reflects, women “often bear the brunt of suffering and exploitation.” And yet, throughout the series, the victimisation implied in “Crying” and “Bleeding” is countered by a resilience of the spirit – the “Kicking” and “Screaming” in the face of terror and trauma.

Rather than withdrawing from the fields of battle, the sites and scenes we are taken aback by, the prints draw us in through an emphatic vision. What is achieved is akin to the works by German artists examining the society of the Weimar Republic – works to which the complicated and hard-to-translate label “Neue Sachlichkeit” came to be applied.

“Sachlichkeit” is anything but an elusive objectivity through clinical detachment; it is a commitment to and figurative rendering of sobering reality. Hanselaar draws on the tradition of art that, as we say in my native German, “geht zur Sache” (gets at it, rigorously). Her social commentary is rooted in art history. In subject matter and execution, it is indebted both to Goya’s print cycle Los desastres de la guerra [Disasters of War] (1810-20), one of which is also on display in the exhibition, and to Der Krieg [The War], a series of etchings the German artist Otto Dix created a century ago in response to the First World War.

Hanselaar was born into the aftermath of the global conflict that followed. Raised in the protestant culture of the Netherlands, she “was told to not show any strong feelings.” In her prints, those emotions come to the fore.

Whereas The Crying Game confronts us with public horrors, prints in the series We’re all bleeding take us behind closed doors. Hanselaar is “fascinated by the secret lives we all lead, those vivid worlds beneath our pleasing and pleasant ways.” She was raised in a restrained, bourgeois environment. To be “collected and contained was considered to be a good thing for yourself as well as pleasing to others.” We’re all bleeding invites us to question ‘who and what we are’ when our “mask is off.”

We “fear our innate savagery,” Hanselaar has commented on her work. Most of us would “prefer to deny its existence.” And yet, we are “compelled to be inquisitive.” The compulsion to dig below the surface of civilised society finds expression in the etching process as acid bites away at the metal plate.

In We’re all bleeding, Hanselaar also hand-coloured her prints for the first time. As a result, each multiple becomes unique. This reflects our shared humanity and the hidden dimensions of our being that set us apart. A voyeuristic impulse is tempered by a longing for understanding of what makes us tick like timebombs.

Kicking and screaming, Hanselaar’s work rattles us into recognition. Etymologically speaking, they remind us that bravura, more than simply wanting to make us go “bravo,” is both bold and brave.

Crying Bleeding Kicking Screaming: Prints by Marcelle Hanselaar from the School of Art Collection is open to the public from 22 May to 29 September 2023. The works on display were purchased with support from the Arts Council England/V&A Purchase Grant Fund and the Art Fund.

Curatorial team: Zoe Bennett, Charly Brown, Heather Bubb, Kinga Fus, Rhiain Knox, Eva Liss, Morganne Lloyd, Emily Miles, Yara Saleh, Hubert Sikorski, Isobelle Smith, Louise Tilby; Harry Heuser (concept and text), Neil Holland (design and staging)

Discover more from Harry Heuser

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

It’s great. Who said they did not have anything new to say. Besides, it’s the way you say it.

LikeLike

Very pleased with your insightful writing and look very much forward to see the new angle on my work. Many thanks to the whole team

warmest M

LikeLike

Great bit of writing

LikeLike