In conjunction with “Gothic Imagination,” a visual culture module I teach at the School of Art, Aberystwyth University, I host an extracurricular festival of films by way of which to skirt the boundaries of the gothic beyond the landmarks and hallmarks of the Gothic as genre.

The Alfred Hitchcock-helmed silent romance thriller The Lodger (1927), a loose adaptation of a short story (1911) and novel (1913) by the suffragette Marie Belloc Lowndes, has featured in each of these series of film screenings—“Treacherous Territories” (2019), “Uneasy Threshold” (2021) and “Significant Othering” (2023). Approaching The Lodger anew, “Significant Othering” concentrates on the gothic or gothicized bodies that—in whole or in parts—figure in the sprawling landscape of movies in the gothic mode.

None of the prime embodiments of the literary Gothic materialize in the films screened. The modally gothic does not depend on the presence of Frankenstein’s creature, Jekyll and Hyde, or Dracula; the multiplicity and hybridity that characterize those familiarly strange bodies are alive—make that “undead”—in the mutations of the gothic mode beyond the permutations of the genre.

As The Lodger drives home, what makes bodies what we might call gothic—although others may argue otherwise—is their otherness or, more precisely, the othering of them.

Set in the present day of 1927 but based on the Whitechapel murders that terrorized London from 1888 to 1891—a period still in living memory when the film was first released—and subsequent speculations surrounding the identity of Jack the Ripper it begot, The Lodger performs an anatomy of panic: it dwells on the suspicion and savagery incited by the haunting specter of an unseen but demonstrably real serial killer—the elusive Avenger—slashing the fabric of civilized society.

While there are no mutilated bodies on view, fragmentation is very much a strategy of The Lodger in terms of storytelling, cinematography and editing alike. Visually, othering is achieved in part through close-ups and the partial disclosure of the human form to suggest the pathology of modern—and particularly urban—living: social disintegration, disembodiment and fetishization. The Lodger appears to caution us as well about our inability collectively to recognize or accept all parts as part of the whole rather than isolating some of them as alien to a complex organism.

When we first meet the eponymous lodger—a role inhabited by the queer Welsh matinee idol, composer and playwright Ivor Novello in a performance that mixes one part Maurice Chevalierian coquettishness with one part Bela Lugosian mystique —his body emerges from the London fog and appears, we know not whence, before a gasping Mrs. Bunting, his future landlady. His face is partially concealed by a scarf, encouraging us, as it does Mrs. Bunting, to wonder and worry: Is it the unwholesome pea-souper that made him keep his throat under wraps, or might he be hiding an unspeakable secret?

The theme of fragmentation and alienation is set even before the lodger comes onto the scene.

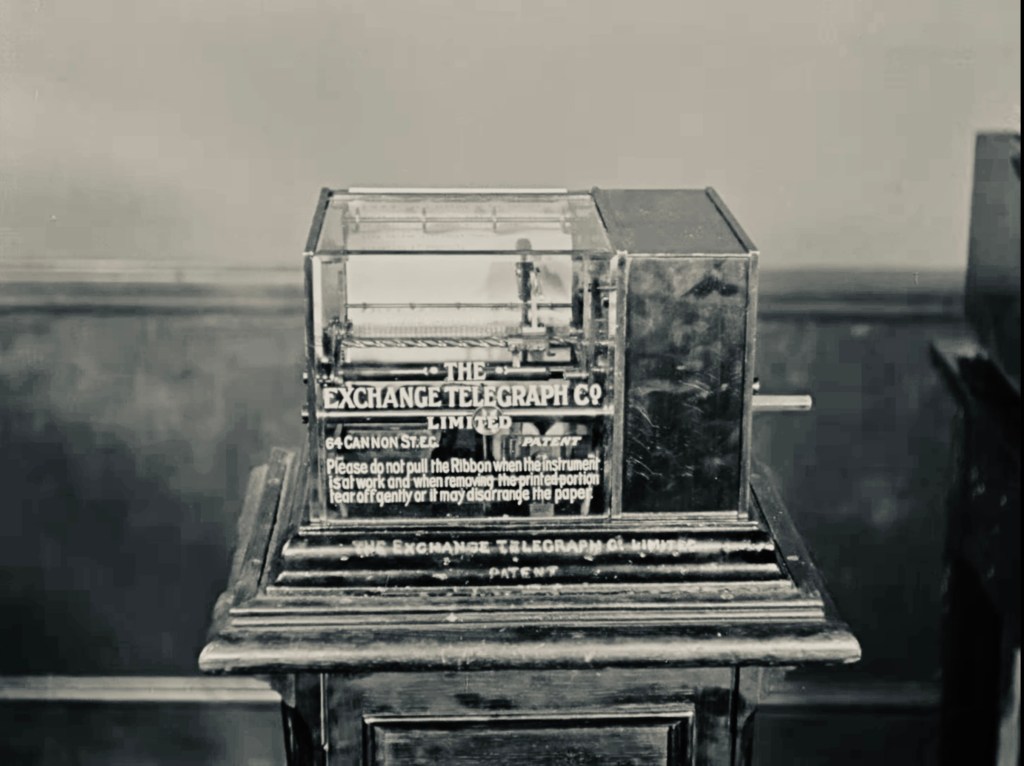

In an elaborate montage showing the arsenal of modern communication technology at work—the printing press, the telegraph, the telephone, the wireless and the electric news ticker—close-ups of isolated figures in the firing line of communication inspire little confidence in the benefits of its workings.

Anxious and non-comprehending, the expressions on the faces of those parcelling out and piecing together snippets of information reveal the failure of the machinery presumably in the service of bringing us closer to the world around us. Exposed to fragments of pictures whose dots we cannot connect, the montage suggests, we become overwrought rather than assured, doubtful rather than informed.

Although the viewer never gets to see the monstrous handiwork of the serial killer at large, close-ups of the lodger’s hand—manicured fingers that alternatively betoken manners, mannerism and mania—there are many.

We watch it furtively reaching for a doorknob, deftly handling a knife and poker, stopping short of fondling the hair of one of the Avenger’s potential victims, and clutching the banister as it glides, as if of its own accord, down the staircase of the Buntings’ home.

Later, we see one hand cuffed to the other, dangling from the rails of a cast-iron fence.

Even when they are absent, those hands speak volumes. Just prior to the climactic scene of entrapment, the lodger’s cuffed hands are hidden beneath his cloak, leaving those around him to imagine his body to be a casualty of the Great War. In an instant, the curiosity of the crowd makes way for rage, compassion cut short by reports that he may be the killer.

Outstretched and grasping, the lodger’s detached hand serves as a visual synecdoche—a figure of speech in which a part is made to represent the whole—for powerlessness.

Meanwhile, power is shown to be in steady but untrustworthy hands. Joe, the police detective involved in tracking down the Avenger, also pursues the Buntings’ daughter, Daisy, a confident, self-assured young woman who models high-end fashion at an extravagant West End palace to couture.

In the Buntings’ kitchen, as Mother Bunting puts down her rolling pin, we witness the off-duty officer using a cookie-cutter approach to courtship when he throws a piece of heart-shaped dough in the direction of Daisy, who is unimpressed by the gesture. His hands then tear the ersatz heart in half, and Joe proves unable to mend his own without tearing Daisy from the lodger, who, through the law’s wilful mishandling of the case, risks being torn to pieces by an angry mob.

Not easily deterred, the officer once again abuses his power by putting the cuffs on Daisy, an ill-judged jest revealing his determination to possess her. Having temporarily lost the use of her hands ultimately drives Daisy into the arms of the lodger, the officer’s rival in love. It is Daisy’s hand that administers a shot of brandy to steady the handcuffed lodger running from the law.

We never learn much about the motivations of the Avenger who, in Belloc Lowndes’s story, is a religious fanatic. What we do know is that he is a fetishist whose victims are blondes, a predilection the serial killer shares with the film’s director. Subject to culturally enabled voyeurism and exploitation, a group of female performers in the review “Golden Curls” become prime targets.

The young women are expected to fuel male fantasies by parading in blonde wigs that, once off stage, they are anxious to shed and exchange for brunette locks in an effort to protect themselves.

The Lodger is not a feminist tract, however; the film objectifies women and implicates the viewer by granting access to the performers’ dressing room and taking us behind the locked door of the Buntings’ bathroom, where Daisy is shown whistling in the bathtub and wriggling her toes in the water, leaving us to imagine her as a breathless victim unable to extricate herself. The camera detaches her legs from her body with the precision of a surgeon or any expert handler of a knife.

Apart or partial, the bodies in The Lodger are gothicised through their isolation from one another and through our estrangement from them. At once familiar and foreign, the body is rendered uncanny.

In one scene, a distorting mirror turns a common body—a man cruelly mocking a witness to murder—into a grotesque creature. The effect is as startling as it is simple. The Lodger reminds us how easily any body may become monstrous to us, how an inability to read faces or interpret gestures makes us vulnerable, and how understanding is inhibited by incomplete representations of ourselves and the lives of others.

While the film adaptation does not make full use of the material offered by Belloc Lowndes’ story, in which Daisy and Mrs. Bunting are joined by the lodger in a tour of Madame Tussauds’ Chamber of Horrors, its “Significant Othering” of the body through fragmentation is nonetheless a tell-tale sign of the gothic mode in operation.

Discover more from Harry Heuser

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.