Cat People (1942) is a legendary and much-loved B-movie […] that, as Geoffrey O’Brien has argued in “Darkness Betrayed,” his notes on the Blu-ray release of Jacques Tourneur’s fantasy film, “manages, over multiple viewings, to break free from its own legend.” Despite the fact that viewers—professional critics, academics and horror film enthusiasts alike—“have sifted every shot and every situation of this seventy-three-minute feature,” O’Brien adds, a “fundamental mysteriousness remains, a slippery unwillingness to submit to final explanation.”

There is no danger of that slippage into certainty happening here. My mind, too, has a “slippery” nature. It is resistant to, and indeed incapable of, any thought amounting to an “explanation” that could possibly be taken for a “final” solution—a terminal reasoning that, bearing my Germany ancestry in mind, has demonstrably shown to bring about and justify no end of horrors.

Cat People was produced at a particular time of uncertainty—and of particular uncertainties—about democratically enshrined equalities, about the limits of reason and the extent to which the stirring of irrational fear could be instrumental in the unfolding of millionfold death. It is fantasy that, rather than being escapist, gets us to the core of uncertainties about the state of humanity, the doubtful definition and futurity of which, a year after the raid on Pearl Harbor and the end of US isolationism, many a cat got many a tongue.

Cat People is “fantastic” in the way the term was proposed by Tzvetan Todorov. In his seminal study The Fantastic(1973), Todorov argues that the phrase “I nearly reached the point of believing” constitutes the “formula” that “sums up the spirit” he calls “fantastic.” Perhaps, that thought, being proposed so declaratively and summarily, itself sounds rather too conclusive. Subverting such reasoning, the “fantastic” exists only because it resists any summing up. To grasp it in this way is to deny it. Its existence is predicated on its elusiveness, on its perceived indeterminacy.

Still, Todorov continues, “The reader’s hesitation” is the “first condition of the fantastic.” Responding to Cat People—and, unlike Todorov, who does not comment on film—I have no qualms about equating “reader” and “viewer,” nor about equating “viewer” for self” for the purpose of these queer notes on an intensely scrutinized film narrative, viewers may hesitate for various reasons. Is Irena truly cursed? Is she a feline in human guise, capable of shifting shape?

Or is she having such anxieties about the consummation of her heteronormative partnership—at a time when no other marriage was widely conceived of, let alone condoned—that, in order to express her apprehensions, she has to resort to the makeshift of legend, a fact-based fiction in which her own impulses and instincts are cast as animalistic and destructive whereas connubial duties, as patriarchally construed, require her to be at once domesticated and restrictively wild—to be a compact of passion for the benefit of a single but no longer single male?

Oliver’s gaze is briefly arrested by a statuette on display in Irena’s apartment. It shows a man—King John of Serbia, Irena explains—in the act of “spearing a cat,” as Oliver puts it. That “not really a cat,” Irena enlightens her prosaic pal. “It’s meant to represent the evil ways” into which her “village had once fallen,” serving up a metaphor about Serbia—a stand-in for much of middle Europe—falling to and falling in line with Nazi Germany (“People bowed down to Satan,” as Irena puts it, “and said their masses to him”).

Such propagandistically obvious reading instructions notwithstanding, the film narrative invites hesitations and the hazarding of guesses. It is constructed as a commentary on the conventions of patriarchy that it is nonetheless designed to uphold, an uncertain response to a developing historical narrative that resonated particularly at a time when US American males were drafted to serve in the war against the Axis, a contested battleground to which Irena, being of a Middle European heritage that her accent—according to the peculiar logic Hollywood, casting French actress Simone Simon in the role—is meant to belie, is dangerously close, while women generally were expected and temporarily granted the opportunity to fill roles that men were forced to vacate at the home front.

In her relationship with Oliver (portrayed with the signature blandness inhabited to alarmin effect by the almost Hollywood A-lister Kent Smith), Irena desires friendship above all. When she invites Oliver into her apartment, it is in hopes that he might be her first “real friend.” This is not the relationship Oliver is after.

“I never wanted to love you,” Irena confides in Oliver as she sits at his feet while he rests on the sofa. And once Oliver becomes—and expects her to be—more or other than a platonic companion, the relationship falls apart. It is, to put it more penetratingly, torn to shreds.

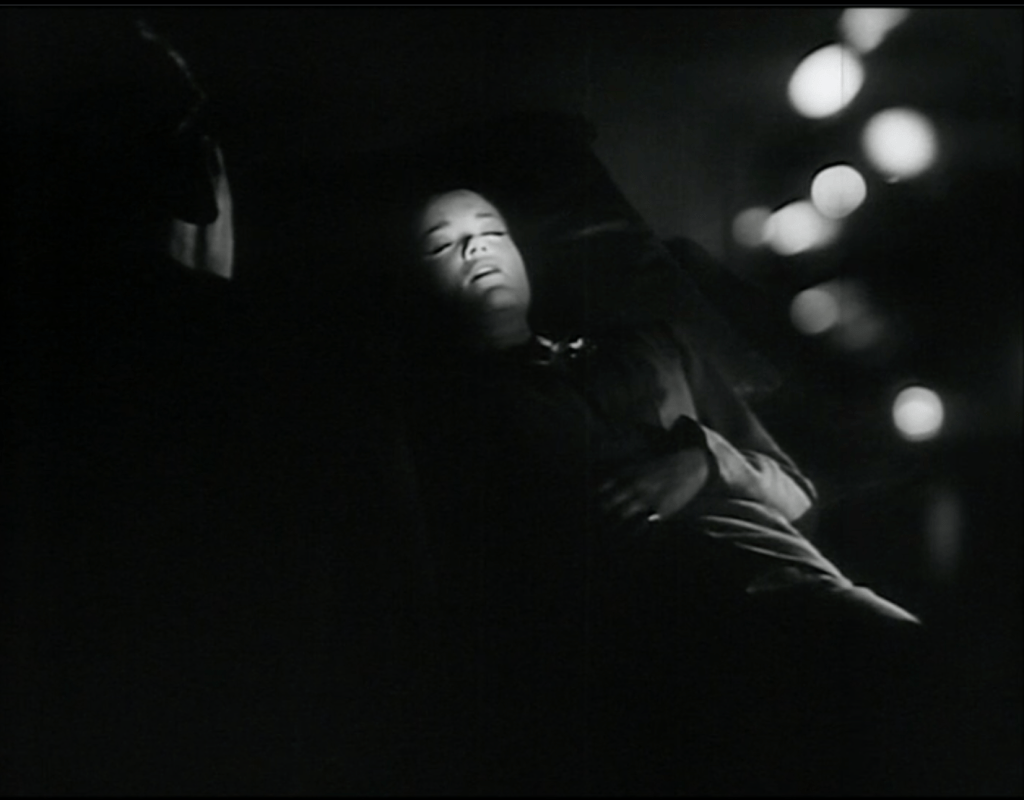

Irena is expected to lie down with her spouse, to make him feel whole while she is of more than one mind—and perhaps of more than one body—regarding the matter of a relationship she initiated as a friendship. To facilitate the intercourse to which Oliver claims to be entitled, she is coaxed into seeing a psychiatrist, Dr. Judd (a menacingly suave Tom Conway), who has her flat on her back and, daring her to kiss him as if for the purposes of therapy, abuses his power.

Pretending to leave his walking stick behind, the less-than-ethical doctor secures access to Irena’s apartment in hopes of setting a trap for her, of straightening her out. Instead, much to the regret of practically no one, he signs his own death sentence. That same sofa that seated Oliver and Irena—but never the two of them together–bears the marks left by Irena’s claws. Being expected to sit up and lie down—to perform like a circus animal whose wildness is reduced to a spectacle—a wounded Irena ultimately claws herself back to the position of a panther. A creature far from free and feral, she returns to and perishes in captivity.

Irena’s offence is that she would much rather stand or curl up than to sit down politely, in feigned equality. Nor can she lie down to oblige. As a modally gothic narrative, what Cat People achieves is giving a voice to those who cannot—or will not—fulfil societal roles expected of them, who struggle to trust and, being mistrusted, struggle to trust themselves; who are speared, not spared, because of their “slippery unwillingness” to “submit” to whatever “solution” a heteronormative vision narrows down as “final.”

Discover more from Harry Heuser

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.