Taking the radio play to the library has long been an ambition of mine, given that dramatic and literary works written for the medium of sound broadcasting occupy comparatively little space on the bookshelves. Taking the first of its kind to a national library—the National Library of Wales, no less—is a chance of a lifetime amounting to poetic justice. Allow me to shed a modicum of light on that, and on my benightedness besides.

So that meaningful conclusions may be drawn from my peculiar challenge of commemorating one hundred years of radio dramatics in just a few minutes, it strikes me as essential that the centenary first be quartered, a fate I hope to escape on 22 February 2024, the date set for the event.

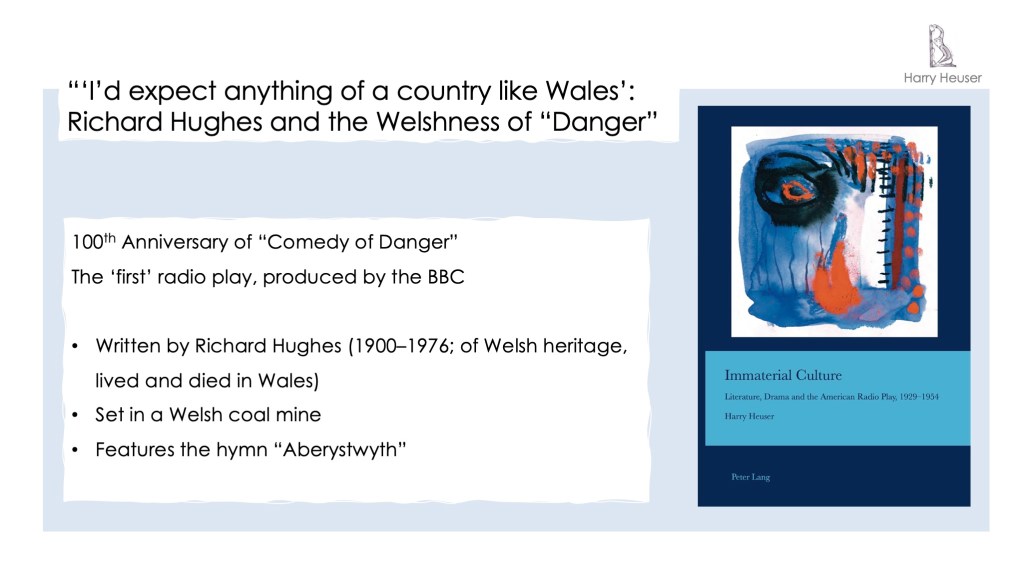

Some twenty-five years ago, as a student of English-language literature, I set out gleefully to trespass on the territory of broadcasting history. The aim was to mix and ditch academic disciplines by considering radio plays in relation to literature, drama and modern media. The project involved turning an enthusiasm for the hybridity and a frustration with the sidelining of those works—along with the thrill and bewilderment of experiencing them belatedly—into the PhD study I fancifully titled Etherized Victorians. Too fancifully, the playwright, poet and journalist Norman Corwin cautioned me; heeding his advice, I eventually settled on Immaterial Culture when I revised and updated my dissertation for publication.

While primarily concerned with plays broadcast in the United States prior to the near terminal supremacy of television in the mid-1950s—to recordings of which I tuned in, more than half a century later, via WBAI, New York—I felt that any writer on the subject needs to acknowledge as seminal a play first broadcast by the BBC in January 2024: Comedy of Danger by the novelist-playwright Richard Hughes.

Written expressly for the wireless, rather than being tossed onto the airwaves like the flotsam and jetsam of materials drawn from stage, screen or print media that, daytime serials and comedy-variety aside, would dominate so-called radio drama in the US and curtail the development and playfulness of the form, Danger was still regarded as experimental when, over a decade after its British premiere, it was performed, its date undisclosed, on US radio as part of the inaugural broadcast of The Columbia Workshop, a sustaining (meaning, not commercially sponsored) program that also showcased Corwin’s plays and was designed, or at least designated, as a “laboratory” of sound.

Practical and resourceful, Danger turns that laboratory into a make-believe coalmine. As I pointed out in my study, the prospect of doing the same to the living rooms of listeners was met with the indignation of a contemporary commentator who scoffed that “one would think a little more might be required.” The democratization or levelling by radio—the ability of radio to tear down regional, cultural and class boundaries by tunnelling through the private quarters of the nation to form a Gemeinschaft (to borrow an apt German word for community that only coincidentally sounds like mineshaft)—was greeted with suspicion from the start.

Danger mines the potentialities of a pitch-black setting for a medium that is sometimes—and somewhat problematically—referred to as “blind.” It may be pulling us in by the ear, but national broadcasting cannot pull the wool over our eyes so as to make us blindly accept that it was class-unconscious or color-blind; and rather than fostering community, state or state-to-state radio was invested in erasing distinctions that, if made audible, would challenge a national, and nationalistic, narrative. The make-believe of serving “everyone” does not necessarily involve a due consideration for—much less an embrace of—the diversity implied in “anyone.”

What I was blind to, upon first listening to Danger, was the political dimension of embedding a British play in the English language into Welsh soil. Would not Pennsylvania have done? Back in the 1990s, despite all the attention paid to identity politics, I never even considered that question and, in the case of Danger, its postcolonial implications. Granted, I had no idea, when first I encountered Danger, that I would one day be moving to Wales, England’s first colony, and live in a town whose name is also the title of a hymn, “Aberystwyth,” which is sung in the play by a distant choir of men representing the Welsh miners coming to the rescue of a group of English tourists who are trapped after a cave-in and about to drown.

Not that the 18 July 1936 Columbia Workshop presentation of Danger features hymn-singing. Besides, only the first of the two mentions of Wales and the Welsh in the play is preserved in the US version, the second reference being a reassessment of the first in light of the disaster and the stoicism of the Welsh miners singing as one the hymn “Ar Hyd y Nos” (Welsh for “all through the night”) while putting their lives at risk to dig out the English sightseers, one of whom a self-confessed thrill-seeker who enjoys playing at danger until realizing herself to be in peril.

“You’re finding some good in the Welsh, then, after all?” Jack, one of the three trapped visitors, tells Bax, a man about two generations his senior who previously exclaimed in exasperation: “I’d expect anything of a country like Wales! They got a climate like the flood and a language like the Tower of Babel, and they go and lure us into the bowels of the earth and turn the lights off. Wretched, incompetent—their houses are full of cockroaches—Ugh!”

Now, where does that anger—and that ignorance—come from? And why is it launched, in a British broadcast, live from London, at the people of Wales? True, the playwright, Richard Hughes—who would go on to write two major novels, A High Wind in Jamaica (1929) and The Fox in the Attic (1961), was born in England, to English parents. His ancestry, if dated back to the time of the Tudors, however, was Welsh, and Hughes identified as Welsh. Relocating to Wales and numbering Welsh painter Augustus John and poet Dylan Thomas among his acquaintances, Hughes was a thorough cymruphile (or lover of Wales), even though that did not stop him from being critical of Wales and its people.

Hughes’s first stage play, The Sisters’ Tragedy, produced in London about nine months prior to the broadcast of Danger is set in a Victorian mansion in the “Welsh hills,” and his second stage play, Comedy of Good and Evil, produced a few months after the broadcast, concerned an Anglo-Welsh family. The published script for the latter came with Hughes’s very specific notes on pronunciation. “The accent,” Hughes pointed out, “is that of the South Snowdon district.” Introducing one character whose “Welsh accent is very noticeable, but attractive,” Hughes insists: “On no account must the audience be allowed to laugh at him.”

There is no Welsh spoken in Danger; nor do Welsh accents feature prominently. As one scholar pointed out as recently as 2022, the Welsh in Danger are not individualized and, apart from singing in the distance or shouting from afar, they have no voice. What Hughes draws attention to, even if he seems to perpetuate it, is the absence of such voices on the air, an absence that was systemic and could not at the time be redressed.

The mine, resonantly gurgling, rumbling and roaring is as much a character in the play as the three visitors from England; along with the choral singing, it is a stereotypical representation of Wales that, however familiar, is demonstrated to be not only perilous but imperiled.

In its philosophizing on life worth saving—the life of the mine, the life of the miners, and the lives of the visitors to the mine—Danger calls out the English as self-absorbed aliens who are presumably as far removed from Welsh culture as are broadcasters in London. In the climax, Hughes kills off the older Englishman, Bax, as if to lay to rest the prejudices of his generation and bury them in the Welsh soil that had been exploited by the English for centuries.

The as yet uncharted territory of radio serves as a stand-in for Wales, a wild, mythical and mysterious country from which, as the irritable Bax declares, “anything” might be expected. A medium in which a crumbling coal mine may be a laboratory for experimentation provides opportunities for cultural renewal and exchange. There is a chance, too, for enlightenment after years of lives being cast in darkness, of dialogue if not in Welsh so at least about Wales and its future.

Hughes, who was in his early twenties when Comedy of Danger first aired, would write further plays for the medium (“Congo Nights,” another play on otherness for listening in darkness, and the reportedly misfiring comedy “We Gave Our Grandmother”); but even though he was also heard on the wireless, speaking from Cardiff, as a commentator on Wales, he did not always sound hopeful about that dialogue or about the status of literature about Wales and its impact on Wales.

About the former he remarked, a quarter century after the first Danger broadcast, that the discourse on Wales by the people of Wales was marred by self-consciousness, that “[i]nstead of talking Welsh as a matter of course,” for instance, “people now talk about talking Welsh”; and that, “instead of being Welsh as a matter of course, we now talk about being Welsh.” Contemplating the possibility of making a meaningful contribution to the culture of Wales by writing about contemporary life in Wales, he threw up his hands: “Honestly, have you ever heard a Welshman have a good word for anything of general appeal ever written about modern Wales?”

Whatever its contribution to the culture of Wales, Comedy of Danger—which was soundstaged again two months after its London premiere and broadcast from Cardiff—certainly made radio history. That about sums up what I knew twenty-five years ago; but what encouraged me to initiate the project of commemorating the one-hundredth anniversary of the play in Wales was to draw out the Welshness of Danger, and the danger of Welshness, as communicated in a short play for radio that highlights England’s dependency on—and silencing of—Wales.

I will be saying as much, or as little, in my brief presentation at the National Library of Wales on 22 February, which is part of a free but ticketed event open to anyone wishing to attend in person or turning in remotely.

“Danger” 1924/2024: Commemorating the (Welsh) Origins of BBC Radio Drama was co-organised by playwright and educator Lucy Gough, who will not only share her experience of working in radio but, assisted by Senior Technical Instructor Chris Stewart from Aberystwyth University, will re-stage the play with a group of student actors and sound effects artists. The event also features talks by Alison Hindell, Radio 4’s Commissioning Editor for Drama and Fiction, and historian Siân Nicholas.

“Danger” 1924/2024 is a collaboration between the National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth University, the BBC, and the Writers’ Guild of Great Britain, whose generous support the event enjoys.

Discover more from Harry Heuser

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.