I had not long arrived in sweltering New York City for a month-long stay in my old neighbourhood on the Upper East Side when I learned that, across the pond, in my second adopted home in Wales, the painter Claudia Williams had died at the age of 90. I first met Williams in 2005. She was conducting research on a series of drawings and paintings commemorating the flooding of a rural Welsh community to create a reservoir designed to benefit industrial England. With my husband and frequent collaborator Robert Meyrick, who had known Williams for years and staged a major exhibition on her in 2000, I co-authored An Intimate Acquaintance, a monograph on the painter in 2013.

A decade later, an article by me on Williams’ paintings was published online by ArtUK on 28 May 2024; and just days before her death on 17 June 2024, I had been interviewed on her work by the National Library of Wales. So, when given the opportunity to write a 1000-word obituary for the London Times, I felt sufficiently rehearsed to sketch an outline of her life and career, as I had done previously on the occasion of her artist-husband Gwilym Prichard’s death in 2015.

Lunch in the yard with Gwilym Prichard and Claudia Williams

All the same, I was concerned that it might be challenging to write another “original” essay, as stipulated by the Times, on an artist about whom I had already said so much and whose accomplishments I was meant to sum up without waxing philosophical or sharing personal reminiscences. In an obituary, salient facts are called for, in chronological order, as is a writer’s ability to determine on and highlight the essentials.

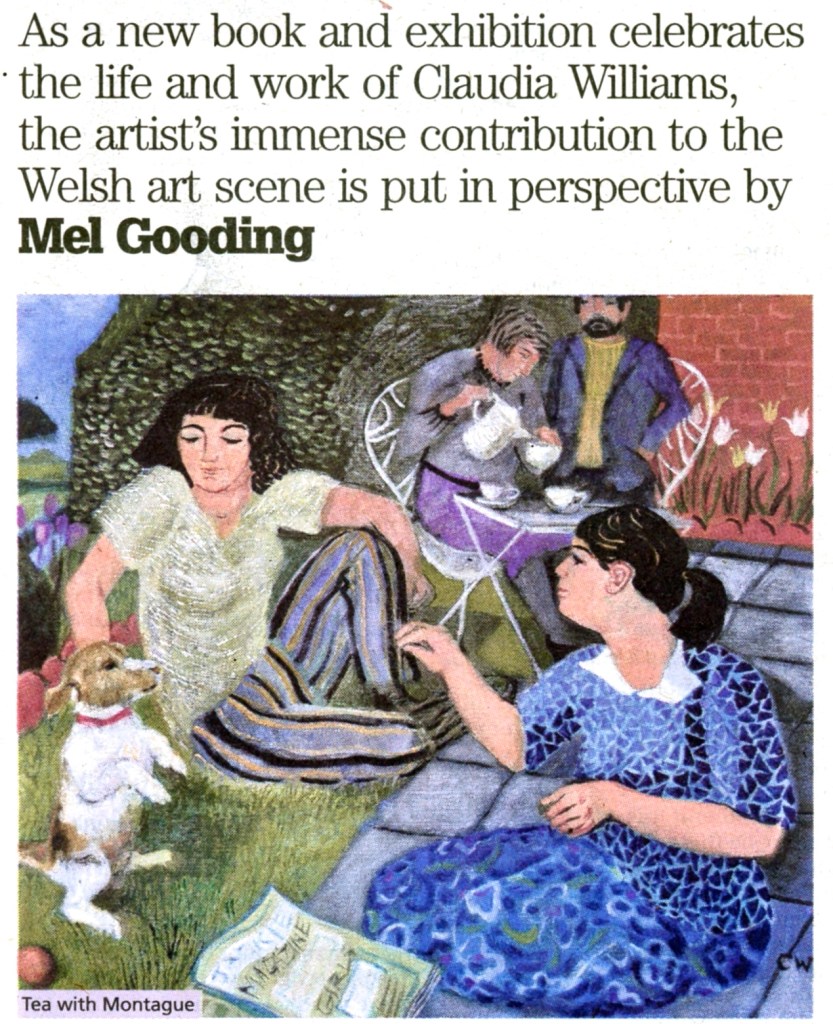

So I omitted recalling the enjoyment Williams derived from watching my Jack Russell terrier begging for food on his hind legs, a sight that inspired her painting Tea with Montague, or the “Mon Dieu” emanating from our bathroom when Williams and her husband, both in their seventies, intrepidly and jointly stepped into the whirlpool bathtub – slight episodes that, for me, capture Williams’ joie de vivre and her enthusiasm for the everyday.

Clipping of a newspaper article on An Intimate Acquaintance featuring my dog Montague as painted by Claudia Williams

In preparation for the monograph, Williams had entrusted me with her teenage diaries and other autobiographical writings, which meant there was plenty of material left on which to draw. Rather than commenting authoritatively on her contributions to British culture, I wanted to let Williams speak as much as possible in her own voice, just as her paintings speak to us, even though we might not always realize how much Williams spoke through them about herself.

What follows is the tribute I submitted to the Times.

The painter Claudia Williams “always loved company.” Her compassion, curiosity and convivial nature come across in the exuberant, often large-scale figure compositions she created during a career spanning seven decades. An only child who would become a mother of four, Williams was a careful – and caring – observer, not only of physical features but of gestures, movements, and human interactions.

Claudia Jane Herington Williams was born on 19 August 1933 in Surrey to Frank Williams, a London-born civil servant, and Gladys Irene (née Herington), the daughter of a Leicestershire milliner and draper who established a successful department store bearing his name. Fabrics and patterns would feature in many of Williams’ paintings.

As Williams noted in her unpublished reminiscences, her middle-aged parents were sometimes at a loss to keep up with their lively daughter. “I expect they discovered fairly soon that this problem could be solved by giving me some crayons (preferably the thick wax kind) and paper to fill lonely moments.” The outgoing child learned to draw on her imagination and survey her environment.

Due to financial difficulties, her parents decided to relocate to the Llŷn Peninsula in North Wales shortly after the end of the Second World War. The Williams family had Welsh ancestors. Williams struggled to adjust to a primarily Welsh-speaking environment and continued her schooling in England. However, she loved living on the Welsh coast, an enthusiasm for the seaside that is reflected in the many beach scenes she later painted.

Williams gained early recognition in 1949 when, at the age of 15, her ink-and-watercolour composition Milking won first prize in the National Exhibition of Children’s Art. Sponsored by the Sunday Pictorial, the competition was open to all schools in the UK and to some institutions abroad. Nearly 47,000 entries were received. Serving as judges were John Rothenstein, then Director of the Tate Gallery, Herbert Read, President of the Society for Education through Art, and Philip James, Director of the Arts Council of Great Britain.

Milking was reproduced in magazines and newspapers, as well as in the book Picture and Pattern-Making by Children. When asked by a reporter whether she wanted to “go in for commercial art or to paint in a ‘big way,’” Williams replied that she wanted to be a painter. “I suppose,” the reporter retorted, “you are going to live in the land of beards, sand[al]s + yellow socks!” Williams was determined to distinguish herself among the “beards” – and in spite of them.

On the strength of her prize-winning performance, Williams was accepted at Chelsea School of Art in 1950. She “often stayed for evening classes” to make sure that she “got in plenty of Life Drawing with a varied collection of tutors,” among them a “very intense” John Berger. In her second year, she was awarded the Christopher Head Scholarship for Drawing.

Despite her accomplishments, Williams abandoned her academic training after meeting her future husband, the landscape painter Gwilym Prichard. The “dark-haired Welshman had swept me off my feet. Rather scandalous in those days,” Williams reflected. It was Williams’ steadfastness and success that emboldened Prichard to follow her lead. The couple married in 1954 and worked alongside each other until Prichard’s death in 2015 at the age of 84. Their enduring partnership and peripatetic life became the subject of several radio and television documentaries.

Beginning in 1952, Williams regularly exhibited at the annual National Eisteddfod. In 1957, her painting Family on the Beach was runner up for the Gold Medal, which was won that year by George Chapman.

The fact that she was a mother who insisted on forging a career for herself attracted the attention of the press in England and Wales. Newspapers carried headlines such as “Artist-Mother Stages Her First Solo exhibition,” “After the children Are Put to Bed …” and “Happy ending to 6 months’ ‘Hard Labour.’”

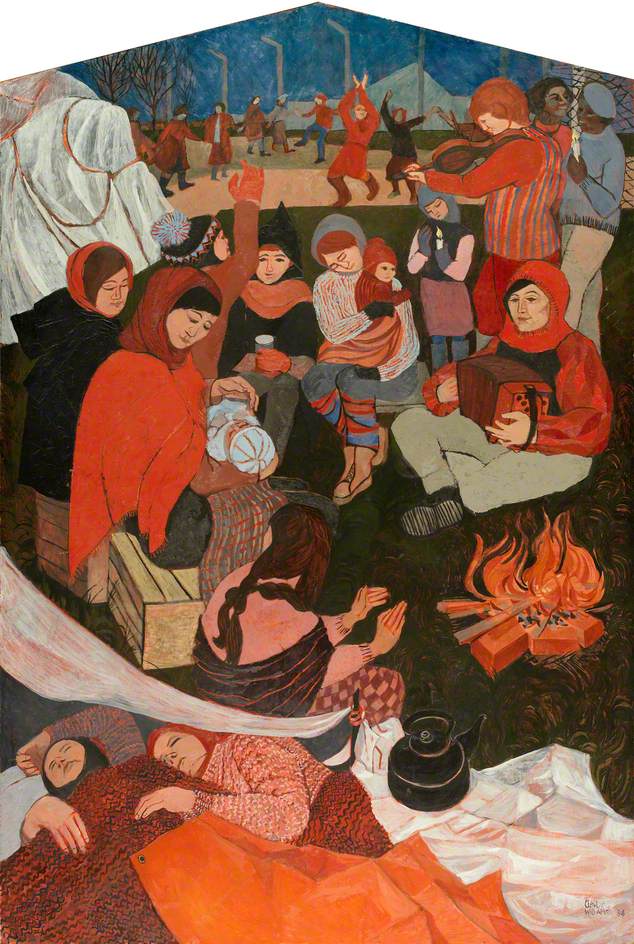

Williams produced many of her most ambitious works after the age of 50. In 1984, she painted Greenham Peace Vigil, now in the National Library of Wales. She had visited Greenham Common in Newbury, Berkshire on several occasions in support of the Women’s Peace Camp erected there in 1981 to demonstrate against the deployment of nuclear tomahawk cruise missiles at the site. Williams’ painting is characteristically celebratory, with clear religious overtones. Williams had converted to Catholicism in 1956 and drew strength from her faith.

Their children grown up, Williams and Prichard decided to give up their home in North Wales and journeyed to Greece in a camper van. It was the start of a seventeen-year-long adventure in Europe. Williams maintained sketchbooks to capture her observations. In Venice, she was “struck by the interesting faces” of the locals. “Here were Bellinis, Botticellis, Leonardos and Piero della Francescas, all living and walking around!”

In 1985, Williams and Prichard rented an old farmhouse in Provence. A year later, they set up a studio in a small house near the harbour at Vannes in Brittany. The couple lived frugally but were encouraged by the interest in their work by French critics and the public alike. In 1992, the couple co-founded the Rochefort School of Creative Arts. Students travelled as far as sixty miles to attend classes in life drawing, watercolour and sculpture. Three years later, Williams and Prichard were awarded the Silver Medal by the Academy of Arts, Sciences and Letters in Paris.

The couple moved back to Wales in 2000 and eventually settled in Tenby. That year, Williams’ homecoming was celebrated by the National Library of Wales with a major retrospective. Williams would return to the Library in 2005 to conduct research for a series of paintings and drawings that would form a touring exhibition commemorating the last days of Tryweryn, a Welsh village that was flooded in 1965 to create a reservoir designed to supply water for Liverpool.

The “community was really treated abominably,” Williams commented. Empathising with the displaced, she drew on her own experience of loss. She remembered the gesture her father made when he was worried about the financial difficulties that forced the Williams family to leave Surrey. Like her father, the farmer in one of her Tryweryn paintings “brushed his forehead with the back of his hand.”

Williams found people “interesting wherever they are.” As her friend, the artist Jonah Jones remarked, Williams approached her subjects, many of which were children, not “from the outside, but from an intimate acquaintance” that is “implicit in her work.”

Harry Heuser

Claudia Jane Herington Williams, born 19 August 1933, died 17 June 2024. She is survived by her four children, Ceri, Ben, Justin and Clare, seven grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

Discover more from Harry Heuser

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Hi Harry,

Thanks for sending this on to me. My interview for Last Word went well, I’m sure they’ll manage to edit any ums and errs! It’s on the airwaves at 4.00 tomorrow and then on BBC sounds.

Best wishes, Ceri

>

LikeLike