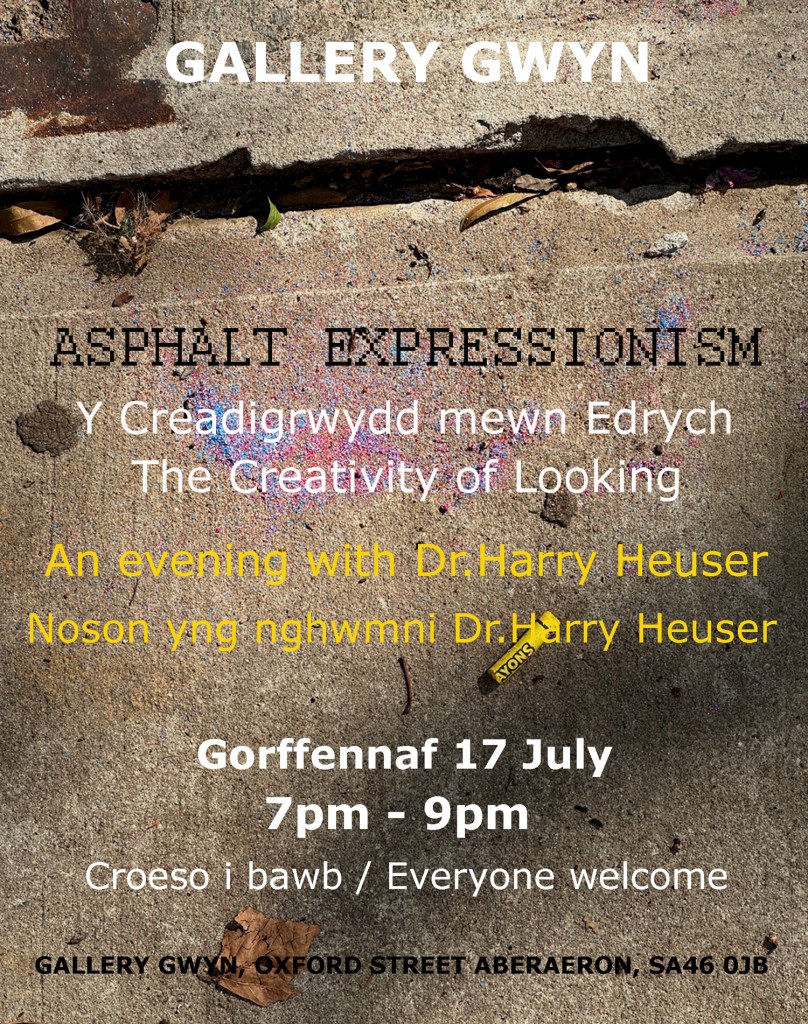

I have been asked, at some point during the run of my exhibition at Gallery Gwyn, to give a talk. I requested that the event be announced as ‘an evening with.’ Asphalt Expressionism was intended to be inclusive and interactive, and the scheduled get-together, likewise, should promote exchange. A conversazione, perhaps, but not a lecture.

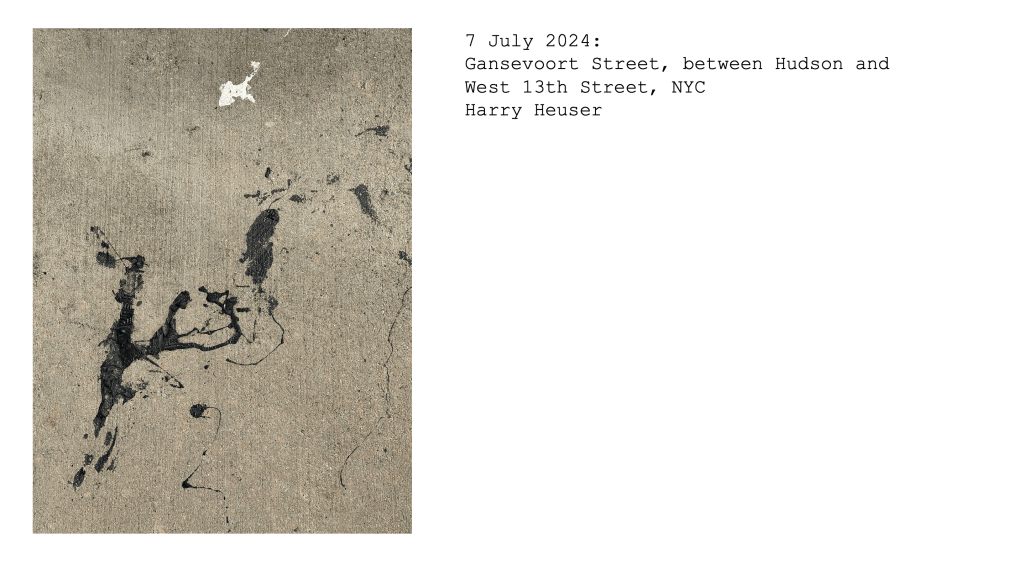

Given that the smartphone is my primary means of creating the images huddled under the fanciful umbrella of Asphalt Expressionism—a series of digital photographs of New York City sidewalks—reference to the ubiquitous technology strikes me as an effective way of connecting with those who, phone no doubt in hand, might be joining me that evening.

As the full title of my project implies, Asphalt Expressionism: Mobile Phone Photography of NYC Pavements would not exist without such technology, even though the display of the resulting images as large-scale prints in a gallery is quite traditional compared to the curatorial potentialities of hosting and disseminating images online, via social media.

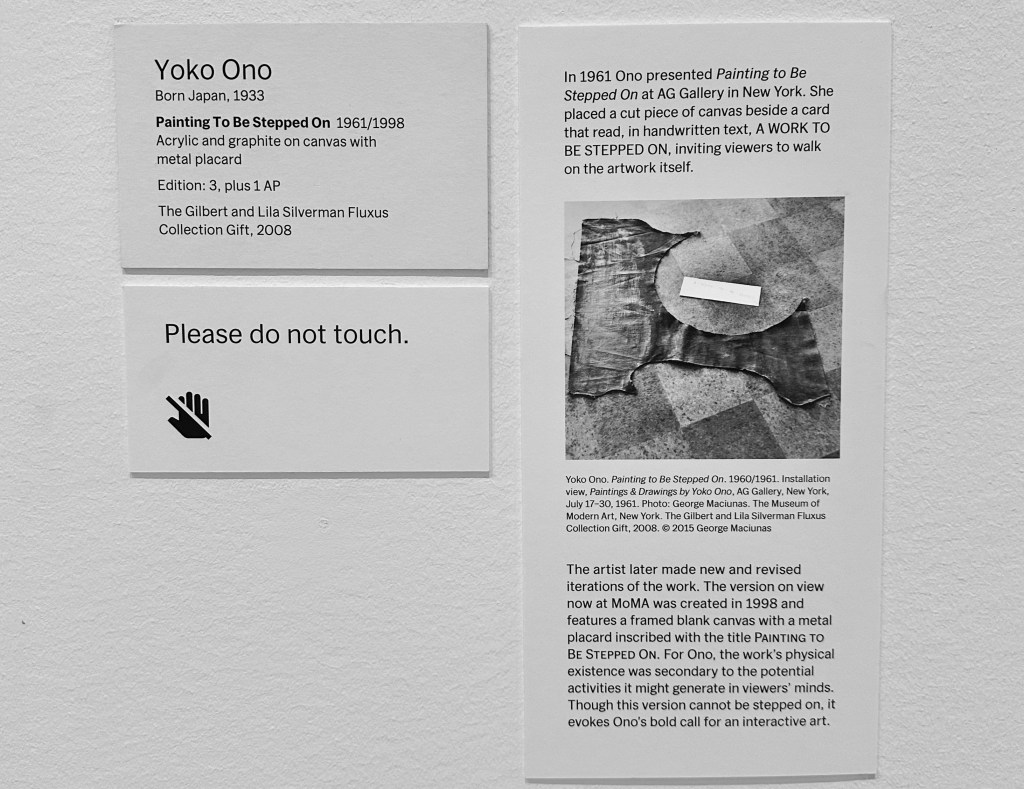

Additional pictures, sent by me via email or WeTransfer to the gallery while abroad, along with solicited contributions by visitors to the gallery, are shown as a digital slide show. As in its previous iteration, Asphalt Expressionism also features one of the images as a vinyl print on the floor of the gallery to encourage, like Yoko Ono’s A Work to Be Stepped On (1960–61), reflections on our engagement with art and the questioning of artwork as permanent, finished products.

Although digital photography does not involve processes of development, it nonetheless unfolds in time, to which Asphalt Expressionism seeks to draw attention in a chronological display of the imaged sites I had stumbled on during my ambulations in the metropolis. As instant as the viral distribution of visuals may now be, the process of imaging, unless impromptu live streaming is the chosen mode of communication, begins before the creation of the content to be shared. It starts with the act of looking and the right to assert our freedom to look, even and especially when not prompted.

In a gallery, our gaze is directed at the objects on show; but that need not stop us from pointing our phone cameras at a smudge on the floor, from looking out for patterns created by shadow and light, or from seeking and seizing an opening—a door or window—to sights beyond the appointed site for seeing in which we are expected jointly to commune with art. In our perceptual congress, we might be arrested by the gaze of fellow visitors or by the looks they sport. Dare we point our lens at them? To what extent are selection and focus a matter of choice, of conditioning, of etiquette?

The smartphone camera, maligned though it often is by eye-rolling highbrows and luddites of the artworld, especially when selfies are involved, can make us more aware of our surroundings. It can help us to situate ourselves or zero in on what we might otherwise assume to be nothing. That is what I have been trying to do with Asphalt Expressionism. Rather than reproduce the readymade, picturesque images multiplied on postcards or in travel brochures, I retrained my vision to take in the world at my feet to discover that the arbitrary and unintentional can have compositional features. Am I looking out for the familiar, after all? Perhaps, but I am doing so in unfamiliar places.

I was in New York again just a few days ago, and it struck me again that almost everyone was clutching a phone. Everywhere I looked, heads were down, eyes diving into the reflective pool of hand-held devices—scrolling, texting, playing games—even while navigating the city’s crowded public spaces—the sidewalks, the subway platforms, the staircases and hallways in which we pass each other.

Less engaged now than ever with our physical surroundings, we inhabit virtual realms of sight and sound, networking remotely on the go. Data roaming turned off for the sake of economy, I was perhaps less prone to such tunings-out, my phone serving primarily as a camera. It is when the lenses of our smartphones are turned into windows that we look up and ahead at something or somebody, be it someone else or at a mirror image of ourselves. However, whether we look at our phones or through them, we rarely take notice of the common ground beneath.

Before it became the symptom of our disconnect, looking down—on or at—was associated with feeling low or thinking less of, with despair or disregard. We still place greater value on and look upon as uplifting what is placed in front of or above us. In many ways, the traditional mounting of art in a gallery determines that value system and defines for us what and where art can or should be. We are confronted with two-dimensional works mainly at eye level while sculptures on pedestals tower over us even when they are life-sized.

In an atmosphere of exclusivity, feelings of awe, reverence and inferiority are engendered by art that is not placed at our feet or at our fingertips. No touching, please! And watch your step! Thus segregated from the everyday, art, we are made to believe, is the rare and precious just beyond our reach, viewing rights to which are temporarily granted, at a cost.

Painting. Sculpture. Those are the media that, despite the diversification of creative practices in the twentieth century, many of us regard as most truly artistic, even though, I suspect, few of us have a clear working definition of ‘art.’ Must art be an object made with skill by a trained individual and set apart from the everyday in institutional settings designated for its display? If so Asphalt Expressionism is not art, and so be it.

Conceiving Asphalt Expressionism, I felt emboldened by the subversive anti-art stance of Dada. I looked toward subsequent practices and strategies of repurposing and appropriation associated with Neo-Dada, Pop and the Pictures Generation—toward practices and approaches that, by questioning distinctions between art and life or between making and being—forced redefinitions of ‘art’ in the 1960s and 1970s. When we consider that the word ‘technology’ is derived from tekhnē, a Greek word meaning ‘art’ or ‘craft,’ we become aware of the spurious and invidious distinctions on which the academic construct of art has been founded.

I much prefer ‘creativity’ over ‘art.’ The former can accommodate approaches that transcend what we conventionally regard as artist, be that science or social practice, innovative thinking or actions undertaken to achieve concrete aims—ways of making something happen, even if that “thing” is merely a conversation starter, an opening of eyes or a raising of brows.

Insinuating itself, for the first time, into a commercial gallery and whispering rather than proclaiming its queer nature, Asphalt Expressionism is profoundly personal. It represents my unease about Western art whose histories I came to teach and interrogate as a writer, educator and curator. Neither an artist nor a detached observer, I was on the lookout for creative alternatives in view of achieving some kind of reconciliation and a sense of belonging.

Decades in the making and slow in emerging, Asphalt Expressionism is reflective of my working-class upbringing in Germany in which art was sidelined in favor of what was deemed to be real work. Central to my project as well are a complicated but enduring romance with New York City that began as a tourist back in 1985 and the fraught relationship with academia that began in 1991, when I decided to go to college so that I might continue to stay in New York City rather than return to my native Germany.

I settled on pursuing a degree in English because I could not afford the materials I thought would be required for the study of art. Even when playing with words, I embraced the supposedly lowest form of wit, the pun, whose to me irresistible draw gave rise to the title of a project that goes in search of the lowly: the “art of ice-cream cones dropped on concrete,” the “majestic art of dog-turds, rising like cathedrals, the “art of scratchings in the asphalt” that Claes Oldenburg declared to be “for” in 1961.

I am for a creativity of looking anywhere and elsewhere, regardless—spite and because of—the general disregard I see for common sites in plain sight.

Discover more from Harry Heuser

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

<

div dir=”ltr”>

Hi Harry,

<

div dir=”ltr”>Are you now back home? I hope all is well and your trip was fruitful. I’ll be back

LikeLike