Delving into the “Draft and Ideas” folder set aside for this blog, I came across a fragment titled “‘Chicago, Germany’: A 1940s Radio Play for Our Parallel Universe.” It was intended for posting on 10 November 2016 as a response to a “Trump administration having become a reality.” The draft was abandoned, but no other piece of writing was published in its place.

In fact, the next entry in this journal did not appear until 15 May 2017, and it coincided with the opening of Alternative Facts, an exhibition I staged with students at the School of Art, Aberystwyth University, in Wales.

As the abandoned fragment and the ensuing hiatus suggest, the “reality” of the Trump presidency had so rattled me that I could not bring myself to continue a blog devoted to the popular culture of yesteryear, as much as I had always tried to de-trivialize bygone trifles not only by examining them in the context of their time but also by relating them to the realities of the present day.

The exhibition project that kept me busy in the interim, had similar aims. Alternative Facts provided me, as a curator and educator, with an opportunity creatively to engage with the outrage of MAGA by appropriating a phrase that encapsulated the duplicity and travesty of those early days of spurious swamp-draining.

Fast forward to 20 January 2025, the day that Trump returned to office, by the popular demand that is a product of his populist brand, with the singular and single-minded vengeance of a MAGA-loomaniac. Pardon the execrable pun, but I find no words other than that crass neologism adequately to describe a US President who pardons rioters storming the Capitol and defecating on democratic principles, much to the Nazi-salute inspiring enthusiasm of enabling, super-empowered and quite literally high-handed oligarchs who, I suspect, will, rather than Elon-gate this reign, eventually assume the gilded let’s-lay-democracy-to-rest-room that, in the interim, is the seat of Trump’s throne,

It struck me that the time was ripe for—and indeed rotten enough—to pick up pieces of that draft in light or dimness of the current and perhaps irrevocably changed political climate, which, far from incidentally, is the only human-made climate change we are likely to hear about from the US government for the duration, as dramatically shortened for our species and for most lifeforms on our planet as that time may have become in the process.

As a melodramatist who staged the end of the earth both on radio and for the movies (in the 1951 nuclear holocaust thriller Five), Arch Oboler would have much to say about all this—except that what Albert Wertheim has called his “penchant for altered reality” was being “married to his anti-fascist zeal” in propaganda plays sponsored by or at least aligned with the objectives of the US government during the FDR years.

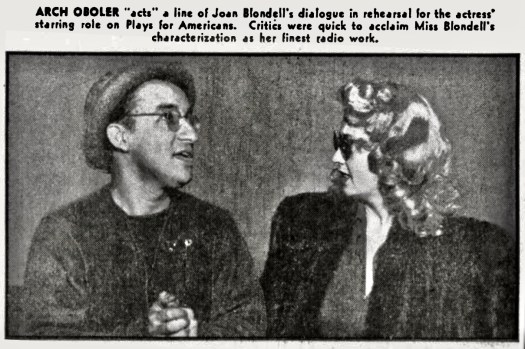

A warning to the listener, Oboler’s “Chicago, Germany” is a dystopia that imagines the extinction of democratic life in the United States. The play was broadcast on 24 May 1942 as part of Oboler’s anthology series Plays for Americans, a sustaining, that is, not commercially sponsored program broadcast via WEAF, New York, over affiliated stations of the NBC network.

“Chicago, Germany” was also produced, with Blondell in the lead, by Treasury Star Parade, a syndicated series designed by the US Treasury to persuade the nation’s home frontliners voluntarily to dig into their pocketbooks to support the war effort. “Remember,” the direct appeal of a radio announcer’s voice implored the listening public,

your quota is at least ten percent of your salary—more, if you can—invested in war savings bonds and stamps. Our watchword must be “WORK, FIGHT, and SAVE.” This is your country. Keep it yours.

Oboler’s play imagines what would happen to that country if it were no longer in the keep of its citizens, presumably because their cash had not been forthcoming.

The first voice we hear is that of an as yet unidentified woman. Talking dispiritedly to her sister, whose grave she came to visit, she tries to recall how “it all started … a year ago.”

A musical bridge carries the audience back to that “terrible day,” a past that, for those tuning in anno 1942, lies about two-and-a-half years in the future: 8 October 1944. “Achtung! Attention!” A German voice states the date and declares that the “army of occupation” has “entered the city limits of Chicago.”

Addressing the implied listeners in the play via the airwaves (a radio voice rendered by means of a filter microphone, a device reserved in radio dramatics for disembodied voices, including folks on the other end of a telephone line, as well as ghosts and unspoken thought), the imperious “Nazi” voice drives home that the broadcast medium on which listeners to the play relied for news and entertainment at home would be among the first casualties of fascism, weaponized by the regime to subjugate US citizens:

This city now is part of the Greater German Reich! Stay in your homes, close to your radio for further orders! Heil Hitler!

Unlike many wartime radio plays, “Chicago, Germany” makes the culprits out of casualties and challenges the conceit of the innocent American. Played by Hollywood actress Joan Blondell—the daughter of a Polish-born Jew whose glamorous likeness startled me years ago on a visit to Dachau—Marion is not simply a victim of extraordinary circumstances beyond her control. By her own belated admission, her inaction contributed to the death of democracy, of which her outspoken dead sister was an embodiment.

“What’s the difference?” Marion’s voice is heard in a flashback as her former self shrugs off the regime change when confronted by her sister, Ann:

To a lot of big shots—army guys, politicians—sure! But what’ve I got to lose? My job? Somebody’ll have to file away things and punch typewriters! You’ll go to school—I’ll go to work—we’ll eat, we’ll sleep, we’ll go on just the way we always have!

Even the rounding up of ordinary people is brushed aside by Marion, who assumes that her life will not change substantially, whoever is in power. “The way your sister Marion explains it,” her mother tells Ann, “they’re just taking inventory! Marion says it’s like a store that’s changed hands. Marion says the new owner wants to know what the stock on hand is.”

Standing at her sister’s grave, Marion can now only reflect in retrospect on the lack of awareness and commitment that cost her, and millions like her, the freedoms she had failed to protect.

They’d won. And what you said was true—there wasn’t any place left in the world for us. And there wasn’t anything I could do about it. We’d lost the war—and I’d helped lose it. And now it was too late. Too late to fight. Too late to even cry.

Oboler’s finger-wagging told-you-so rebuke to the detached members of a faceless crowd sitting at home in splendid isolation was ameliorated by the assurance that, unlike Marion, they still had a chance to mend their ways and come together for the common good. “Chicago, America,” after all, was a copy of an alternative future that could yet be redrafted: “This has been a play of an America that must never happen—that will never happen!”

In “Why Chicago, Germany?”—a note attached to the script published in the popular magazine Radio Life—Oboler reasoned:

There are people who think they can live apart from the world. They think that because they are not in the limelight, or haven’t got a great deal of money, the winning of the war or the losing of it is not of primary importance.

“I don’t expect much out of life,” one of these individuals recently said to me. “Enough food, a place to sleep, a little affection win the war or lose the war, I’ll always get that.”

And so the play “Chicago, Germany: came into being, a drama written quickly and in the heat of wanting to show the truth that if we lose this war to the international gangsters, there will be no life, in its true meaning, for either the great or the little people of this world.

Without equating the serious encroachment on democratic principles by a democratically elected government with the fictional invasion of the United States by Nazi Germany, I could not help thinking that Oboler’s per-version of an “America that must never happen—that will never happen” has indeed happened, only that, like the January 6 riots, evidence of which the US Department of Justice is now erasing, this deluge of a sea change has been happening from within a country turning on itself and turning its back to the Constitution, including the Fourteenth Amendment grants citizenship to “[a]ll persons born or naturalized in the United States.”

The Third Reich stripped Jews of their rights by first declaring them to be non-citizens so that they could be disposed of as non-humans. Writing this on the eightieth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz on 27 January 1945—and at a moment in time when Elon Musk calls on crowds at a far-right rally in Germany to forget the past and get past any feeling of collective guilt—I am appalled at the inhumanity of an emerging regime predicated on exclusion, expulsion and exceptionalism, a nation in which “We the People” is being expunged to make way for autocratic, oligarchic rule.

When the script for “Chicago, Germany” appeared in an anthology devoted to the plays heard on Treasury Star Parade (1942), the US Secretary of the Treasury, Henry Morgenthau, Jr., in his introduction to the volume, expressed the conviction that “American teamwork” would “build a peace in which the common people of the earth can live in harmony, justice and freedom.”

Granted, the US has a long history of disenfranchisement and (neo-)imperialism; but, faced with the graveyard of ideals formerly known as the land of liberty I dread that “American teamwork” is being replaced by forced labor in the service of a system that pits “common people” against each other at the expense of—and to dispense with—“common” goals such as “harmony, justice and freedom.”

In “Chicago, Germany,” Oboler acknowledges only the apathy that undermines the accomplishment of such goals. He did not concern himself with the latent fascism of (some of) the “common people” that is being activated by MAGA. Nor did Oboler have to worry about the demise of a legacy medium such as radio and the bubble-fication in the age of social media. He could presume a public that could be united, common ground that had not yet been hollowed out for the interment of principle and beliefs.

Defending tactics some contemporaries decried as fearmongering and incitement to hatred, Oboler, speaking at the thirteenth annual conference of the Institute for Education by Radio in Columbus, Ohio, argued that what had “prevented” the nation “from facing at once the realities of fascism” was the

fantasy of a Hollywood-born belief that right must always triumph […]. We were not prepared for the realism of ruthlessness—and the phony Hollywood motion-picture romance, aided and abetted by the soap-opera level of radio drama, was largely to blame for our mass self-hypnosis.

Aside from the fact that soap operas like Life Can Be Beautiful, from which Oboler is anxious to distinguish his writing, were put in the service of anti-fascist propaganda not dissimilar to “Chicago, Germany,” as Siegel and Siegel point out in Radio and the Jews (2008), Oboler was also too prone to generalizations to consider the “mass” he declares to suffer from “self-hypnosis” in its constituent parts—the very parts that make democracy worth saving as a whole. Marion’s dismissive “What’s the difference?” also applies to the portrait of her as loosely sketched by Oboler, himself the son of Jewish immigrants from Latvia.

At a round-table meeting following his talk at the Institute for Education by Radio—a talk whose advocacy of “indoctrination” by radio was met in the journal Common Sense by Harvard Professor of Government Carl Joachim Friedrich with the rejoinder “Can the methods of a Goebbels fashion the mind of a new democracy?”—Oboler was so vague as to be unable meaningfully to respond to a question posed by John G. Turner, Public Relations Director of Bennett College in Greensboro, North Carolina.

“Mr. Oboler,” the representative of the all-black institution of higher learning observed,

you mentioned hate and the war psychology. We are living in a world of hate here in America. We have been for years pitting one against another, blacks against whites, Jews against Gentiles. People have been living in traditions years old. I am wondering what you are going to do with that kind of hate in this time of war.

“First problems, first,” Oboler replied. “I think our primary objective must be beating Schickelgruber and Company.” Turner countered by stating that Oboler was “evading the issue,” a concern addressed by Oboler’s fellow playwright, the journalist and poet Norman Corwin, who remarked:

I think that what who think that what you are describing is Fascism at home. The enemy at home is the anti-Semite; the fomenter of class and racial hatred in this country is an extremely effective agent of the enemy, whether or not he is paid by the Axis, and whether we are attacking the hate which exists here or the hate which exists abroad, it is the same fight.

Turner, who would write about “Radio at Bennett College” in the January 1943 issue of Opportunity, was not convinced that those fighting on the airwaves for the survival of democracy grasped the lack of diversity and representation on the air that minorities faced, the very diversity those freedom-fighters presumed to defend in their attack on a system of government they assumed to be universally despised.

Corwin came to the to him “logical conclusion” that if “people […] understand the nature of Fascism,” they would “automatically hate it. The people who hate Fascism most are those who understand it best.”

To some extent, “common ground” has always been a construct. In 1942, it was an expedient shorthand for the government’s need to harness the powers and tie together the divergent multitudes, some groups among which were programmatically sidelined. That sidelining is once again in full swing, now that previous efforts to promote diversity, equality and inclusion are being negated, to the apparent elation of those who were manipulated into believing such measures to be not merely superfluous but anti-American.

But who among those “common” people whose fears of wokeism have been stoked, then put to rest, still fears fascism? To appropriate and adjust FDR’s famous statement for the altered reality of our times, the only “thing” we have to fear is not “fear itself,” but the absence of existential angst within a growing segment of an increasingly history-resistant electorate for whom fascism is no longer a “thing” to dread.

Discover more from Harry Heuser

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Another excellent piece, Harry! The whole situation is scary!

LikeLike

Thank you, Bill. Yes, “scary.” Writing helps me process what is going on.

LikeLike

I enjoyed this piece. Do you have a transcript of the round-table discussion following Oboler’s talk at the meeting of the Institute for Education by Radio? Do you have a transcript of Oboler’s talk at the meeting of the Institute for Education by radio? If not, do you know where these transcripts are held? I have been doing research at the Arch Oboler Collection in the Library of Congress, and I have not been able to locate these transcripts so far. I have, however, located the original program for this meeting of the Institute for Education by radio. Lastly, what journal edition of Common Sense features the referenced essay by Professor of Government Carl Joachim Friedrich?

Best–Matt

LikeLike