“This is Douglas Miller speaking. I’ll be very blunt and to the point. I want to give you a picture of Nazi trade methods and Nazi business methods as I saw them during my fifteen years in Berlin.” Intimate and immediate in the means and manner in which, in the days before television and internet, only network radio could reach the multitudes of the home front, the speaker addressed anybody and somebody—the statistical masses and the actual individual tuning in. The objective was to persuade the US American public that “You Can’t Do Business with Hitler.”

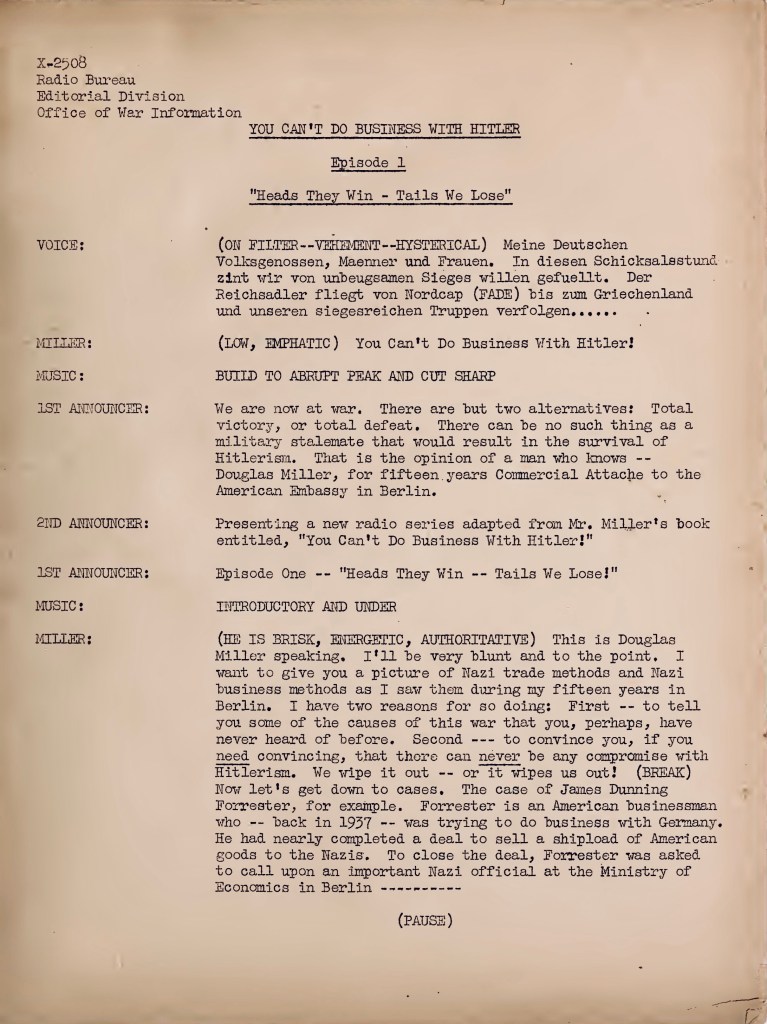

The statement served as the title of a radio program that first went on the air not long after the US entered the Second World War in the aftermath of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, an act of aggression that prompted the United States, and US radio, to abandon its isolationist stance. Overnight, the advertising medium of radio was being retooled for the purposes of propaganda, employed in ways that were not unlike the methods used in Nazi Germany.

You Can’t Do Business with Hitler was also the title of a book by Miller on which the radio series was based. Upon its publication, lengthy excerpts appeared in the July 1941 issue of The Atlantic Monthly, the editor of which introduced the article by pointing out that Miller had personally “observed German industry and particularly noted the ruthless determination with which it was directed after Hitler came to power.”

During the 1920s and ‘30s, Miller had served as Commercial Attache to the American Embassy in Berlin and had subsequently written an account of his experience. In You Can’t Do Business with Hitler, he argued that his long record of service “entitle[d]” him “to make public some of [his] experiences with the Nazis and—after drawing conclusions from them, discussing Nazi aims and methods—to project existing Nazi policy into the future and describe what sort of world we shall have to live in if Hitler wins.”

Posting this—the 855th—entry in my blog, on the day after the national election in Germany in 2025, in which the far-right, stirred by Elon Musk and JD Vance, chalked up massive gains, and in the wake of the directives and invectives with which the second Trump administration redefined US relations with many of its global trading partners—I, too, am projecting, anticipating what “sort of world” we shall find or lose ourselves if “Nazi methods” take hold in and of western democracies.

Far from retreating into the past with a twist of the proverbial dial, I am listening anew to anti-fascist US radio programs of the 1940s to reflect on the MAGA agenda in relation to the strategies of the Third Reich regime, asking myself: Can the world afford to do business with bullies?

A transcribed program (that is, recorded rather than, as was general practice, broadcast live), You Can’t Do Business with Hitler was carried by more than six hundred stations nationwide. As one contemporary source pointed out, all costs, including “recordings, actors, music, sound effects were paid by the government.” Responsible for the production was the Office for Emergency Management, an Executive Office of the US President that was established in 1940, at a time when the US was still officially neutral but preparing for an involvement in the emerging global conflict.

The Office for Emergency Management is a precursor to FEMA, if you can imagine FEMA, or any other federal agency of the US still being able to manage even the emergency thrust upon it by an administration whose swift implementation of its ruthless MAGAgenda marks the radical shift toward a fascistoid epoch in US history characterized by the dismantling of democracy in principle and fact.

According to Donald W. Riley, in his 1944 Ohio State University dissertation “A History of American Radio Drama from 1919 to 1944,” You Can’t Do Business With Hitler was one of the programs that “lifted the ban on radio’s open presentation of international affairs, and to some extent on national issues.”

Writing at wartime, Riley confounded polemics with the truthfulness he termed “open.” You Can’t Do Business With Hitler, which was, according to the program’s credits, “prepared and directed by Frank Telford,” was less about the “open presentation of international affairs” than about the unequivocal representation of the newly, if, from a British perspective, belatedly declared enemy—the Third Reich.

As historian Howard Blue put it, “Miller’s book stressed that Germany was using business as a weapon in its effort to achieve global domination.” The radio program, for the most part, focussed on the theme of commerce and trade, as episode titles such as “No American Goods Wanted” and “Money Talks with a German Accent” suggest.

Statements like “The totalitarians are a group of bandits who have learned no useful trade or occupation but are well armed and have no scruples about attacking their neighbors” made You Can’t Do Business With Hitler a ready source of anti-fascist radio propaganda.

Three incidents recorded in Miller’s book, itself at times anecdotal and lacking in documentation, are dramatized in the first episode of the radio series, ominously titled “Heads They Win—Tails You Lose.” One of the examples of “Nazi business methods” adapted from Miller’s journalistic account and crudely reenacted—replete with the voice caricatures reserved for the Hun, a stand-in for Nazi Germany hissing in the English tongue like a polyglot viper—concerns cases of US American firms that, attempting to make deals with Nazi Germany, were

compelled to ship their goods on German ships, use German insurance companies, make a contract enforceable under German law and in German courts, provide at their own expense for German inspectors who came to this country in advance of shipments. The Nazis even insisted that contracts made with German firms should carry a printed clause to the effect that “this contract is made under National Socialist principles.” No American knew what National Socialist principles were, and we were never able to find out in advance. In practice, however, this meant that the American firm was strictly bound to the contract but that the Germans were able to get out of it at any time by quoting such versions of National Socialist principles as they cared to apply at the moment.

“We must get this straight once and for all,” Miller sums up in his chapter “Nazi Plans for World Expansion” and reiterates on the radio program, “there is no such thing as having purely economic relations with the totalitarian states. Every business deal carries with it political, military, social, [and] propaganda implications.”

If the methods detailed in Miller’s book and the broadcasts based on it resonate with at least some of us today, it is because they are methods being employed now, as the Trump administration demands mineral rights from a country under siege whose invader the US government not only refuses to acknowledge and name as an attacker but with whom it is colluding to undermine the sovereignty of the assailed nation. Can—or should—you do business with a bully that threatens to impose tariffs on neighbors or makes funding to states contingent on their adherence to his rule as a self-styled would-be monarch?

I hope—but doubt—that nations around the world will stand up to the heavy as which the US government has decided to cast itself and reject to engage in so-called “economic relations” that, being neo-colonial and imperialist in nature, are inimical to an agreeing party’s chances of existing as anything other than an outpost to the United States of America, if not an annex.

I also hope—but doubt as well—that US American companies, states and citizens can stand up to and withstand the current administration. Mind, you can do business with bullies—but the business you do with them, doing their bidding, will no longer be yours to mind.

The first US radio program of its kind, You Can’t Do Business with Hitler launched what one contemporary critic, Sherman H. Dryer (Director of Radio Productions at the University of Chicago), called “hard-hitting attacks against the Nazis.” The broadcasts “were so hard-hitting and so loaded,” he added, “that much of their potential effectiveness was probably lost.”

Is “effectiveness” mainly a matter of technique? What makes us tune out the warning voices of the past while present-day demagogues make it their business to cajole and gaslight? And why, standing on this ramshackle soapbox of my own making, going on without attracting audiences amounting to a crowd, do I refuse to mind what some presume to be my “own” business—whatever the business of a Wales-based German citizen whose college and university education is US American might rightfully be—but instead, calling forgotten voices to mind, relate minor historical notes to the major currents of the present day?

I am reminded of this passage from Carl L. Becker’s essay “What Are Historic Facts?” (delivered as a speech in 1926 but not published until 1955). Becker, who died just weeks before the end of the Second World War, argued that it is “not wholly the historian’s fault” that the masses

will not read good history willingly and with understanding; but I think we should not be too complacent about it. The recent World War leaves us with little ground indeed for being complacent about anything; but certainly it furnishes us with no reason for supposing that historical research has much influence on the course of events.

What is “good” history if it is not good for something, not fit for future purpose? If I am attracted to flimsy or downright shoddy materials, as seemingly marginal as an old radio program, it is because I am mindful of our propensity of overlooking and ignoring, our ready dismissal of alleged ephemera in which I perceive a potential for renewed relevance. As Becker puts it, the “past is a kind of screen upon which we project our vision of the future; and it is indeed a moving picture, borrowing much of its form and color from our fears and aspirations….”

We can’t do business with Hitler for the obvious reason of his demise. But it doesn’t follow that we cannot learn from “Hitlerism”—and from a propaganda broadcast on the subject of same—in order to review the businesses we may or may not have with Trump, Putin or Musk or any oligarch intent on defining our future, preferably without our considered input.

Discover more from Harry Heuser

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.