When, at the 2026 World Economic Forum in Davos, the forty-seventh and perhaps last elected President of the United States, in one of his characteristic falsehood-and-insult-littered tirades, referred to Greenland, an autonomous territory of Denmark he had long coveted, as “a piece of ice,” his imperialism, imperiousness and imperviousness to historical facts were once again on blindingly stark display.

Greenland, Iceland, or whatever the misleader of the fabled free world may call the largest island of them all—if indeed it is land, or a land, rather than a frozen asset on the verge of liquidation—it needed to be his, outright. Until, that is, Number 47 (previously 45 but never adding up to more than number two) was duped into settling for cubes portioned out in a deal existing since 1951. Put that in your Diet Coke and drink it, sucker!

“A piece of ice.” Is not Melania enough? Well, not according to the Epstein files, if ever we get to see them entire and unredacted. The likely scenario of hell freezing over comes to mind, boggled though it is.

“A piece of ice.” That, clearly, is what cultures and communities—history and humanity—are to a rapacious tyke-oon, a petulant plutocrat whose crude, rudimentary vocabulary and short attention span remind us daily how limited his definition of “great” is and how precisely that limitation sums up the narrow mind of a bottom feeder—a Moron-roe Doctrinaire?—raised, none too loftily, on the notion that anyone aspiring to be a big fish needs to swallow whatever comes or gets into his way.

Greatness, thus conceived, means little more than to amass much to amount to more in the eyes of the world he, in a less-than-popular deviation from his America First agenda, has set his greedy peepers on.

“A piece of ice,” indeed! The word is chilling enough as an acronym, when it refers to a deadly experiment in cryotherapy involving the deep-freezing of democracy until it falls off the body politic as if it were an unwelcome and unsightly growth.

While I could not gauge the degree of ire among the largely undemonstrative audience at Davos, the phrase certainly made my blood boil, as does pretty much every exhausting waste of air emanating from a hothead whose actions are raising the global temperature as perilously as the actual warming his administration has chosen to deny for the opportunity of raking in a final few billions. When Number 47 talks Greenland, you can bet he means greenbacks.

It is undeniably global warming that makes the island of Kalaallit Nunaat more strategic a region than it ever was, now that melting ice caps open routes and facilitate access to the Arctic.

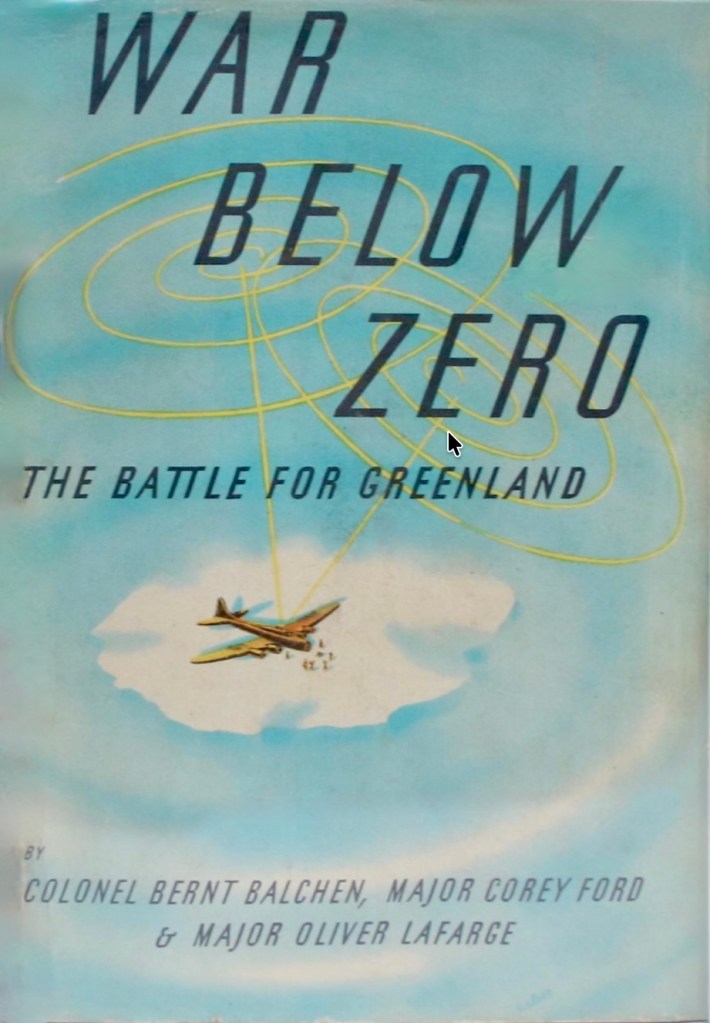

Climate change was not yet an issue during the so-called “Battle for Greenland”—the subtitle and subject of War Below Zero, a book published in 1944. And yet, atmospheric conditions and the ability to forecast them on location were apparently key to the US interest in the region in a pre-satellite age.

According to War Below Zero, the conflict in question was not a war for “territory” but “a war for weather.”

Perhaps you did not even know there was a war in Greenland. It was a secret war, waged in semi-darkness north of the Arctic Circle, on a remote battlefield perpetually locked under ten thousand feet of solid ice. The weapons were not tommy-guns and tanks; the real heroes of this war were nameless enlisted men working in Air Force ground crews at fifty below zero, or standing guard on Coast Guard cutters fighting through the pack-ice, or living all winter long in isolated weather stations along the Ice Cap, buried under eighteen feet of snow. Once each day they would tunnel to the surface to take their wind and temperature readings; the rest of the time there was nothing to do but wait.

To support this premise, War Below Zero starts out as a photographic essay that introduces its audience—US American home fronters living around the time of the conception of a future president now known for the art of the conception of a deal—to an environment the authors and editors of the book vaguely situate on the map that readers are urged to consult as a place “Where the Storms are Born.”

Look at your map, and you will see that Greenland sits at the top of the globe, the nearest landmass to the North Pole. From this frozen island in the Arctic flow winds and currents that set up the storm fronts for all the North Atlantic, for England, for Norway, for the continent itself. Greenland holds the key to tomorrow’s weather in Europe. Every bombing raid we make over Germany depends on our long-range forecasts from the Arctic. The timing, indeed the very success, of our invasion may hinge on the fact that we—and not the Nazis—have Greenland today.

To be sure, the assertion “we … have Greenland” was as dubious then as it is today. In War Below Zero, the sanctioning of US operations in Greenland is explained thus:

Originally both Greenland and Iceland belonged to Norway; they were ceded to the Danes at the Treaty of Kiel in 1821. After the Nazi invasion of Denmark, Iceland became free; but Greenland is still a colony of Denmark, administered from the Free Danish Legation in Washington. It was the Free Danes who gave us permission to install bases and landing fields on this vital Atlantic outpost.

Permission, not possession. As the reference to “the fact” that “we … have Greenland today” suggests, however, the writers of War Below Zero did not bother with the distinction. There are only a few mentions of the allies that had been fighting well before the US entered the conflict. Mentions of their shared enemy there are many.

War Below Zero recounts the challenges of a US “mission” to “establish the northernmost American air base in the world” with the purpose of stopping Nazi Germany from using Greenland as a base from which to “send advance weather information to Nazi merchant ships,” information that “enabled” the enemy to “carry Axis supplies from Norway to Singapore and the East Indies and Japan.”

The Germans knew the importance of Greenland. From the outset of the war Nazi weather planes had been patrolling its coast; it was advance information from Greenland that enabled the trapped Scharnhorst and Gneisenau to slip out of Holland, under cover of heavy fog, and pass unmolested within fifteen miles of the Dover coast. For a quarter-century, alleged German scientific expeditions had actually been studying the Arctic with an eye to its future military use; their so-called good-will flights across the Atlantic, by way of Greenland, had amassed invaluable data […].

Weather forecasting aside, the paragraph that follows states what has become so familiar to us again in a twenty-first century context:

We likewise knew that Greenland was an important frontier. Long before our formal entry into the global struggle, we realized that it would be an essential springboard for any Nazi air-and-sea assault on the North American continent. But our concern was not only with hemispheric defense; we had another vital interest in this obscure island. Look at your map again: the Great Circle course, the shortest air route to Europe, lies across its southern tip. Greenland is a logical stopover point in ferrying fighter planes and bombers to our Eighth Air Force in Britain. We would need adequate bases and landing strips and weather stations in the Arctic, we saw, if we ever hoped to launch any thousand-plane raids on Berlin.

The seriousness of the matter at hand notwithstanding, “Greenland Adventure,” the first part of War Below Zero, is an at times incongruously light-hearted account of the US presence in Greenland, related anecdotally through the eyes of naïve but brave men who, hailing from places like Texas, exclaimed in amazement when approaching the Archtic: “That’s the most ice I ever seen outside of a mint julep.”

Ignorance—passed off as innocence—is at the frozen heart of genial moments like this one in which a spurious legend not only substitutes for cultural insight but also lays bare the imperialist worldview underlying the “mission” carried out on that “important frontier”:

There was a significant ceremony aboard our troop ship as we crossed the Circle. For days we had been plowing through monotonous gray seas; now for the first time we could make out a row of snow-capped mountains like stationary white clouds on the northern horizon. At noon, as our bows sliced across the mythical Arctic line, a blast of bugles sounded assembly, and the entire company gathered expectantly on the after-deck. With an appropriate fanfare of trumpets, and several impromptu wolf-calls from the crew, King Borealis and his royal court came aboard.

His Northern Majesty was an impressive figure. He wore a regal crown consisting of a trench helmet liberally coated with white flour paste; a sheet borrowed from the ship’s sick-bay hung from his shoulders clear down to the soles of his broad-toed Army shoes; behind his foaming cotton beard, the cauliflower-eared features of the mess sergeant peered belligerently. One shaggy tattooed arm protruded from the folds of the sheet, gripping a black dog-whip, symbolic of His Majesty’s authority in the Arctic. Behind him were grouped his official staff, including Santa Claus and the King’s two regular helpers, Frost and Hunger.

One by one the enlisted men in the crew were summoned before him, King Borealis unfolded a scroll, and read aloud the oath of Arctic Brotherhood:

To all soldiers, sailors and civilians, to all polar bears and seals, to all ptarmigans and narwhals: greetings. Know ye that this GI pioneer, having crossed the Arctic Circle, is hereby accorded membership in our ancient and secret society of the frozen North. Let all my subjects henceforth treat him with the proper amount of respect.

Two buglers blew a fanfare, the certificate was the initiate, he bowed low to the King, and returned to his place, grinning. I watched the men curiously as they took their oaths. I was sure that none of them had any real conception of what we were heading into; I was just as sure that none of them would have turned back if he had.

Clearly, “none of them” had “any real conception” of geography or world history, either. In the country of the blind-sided, the snow-blind man is king.

A short passage concerned with the history of Greenland ends in what reads like a foreshadowing of future attempts to lay claim to the island:

The island’s somewhat over-optimistic name was given by Eric the Red, who discovered it about AD 900, and who called it Greenland in order to lure settlers from Iceland and Norway. This first real-estate promotion scheme was not a permanent success.

If War Below Zero were republished as a work of propaganda today, the “real-estate” reference would no doubt be followed by a touting of the accomplishments of Number 47, who, minerals and munitions aside, might well envision Greenland USA as the Arctic Riviera.

Greenland’s minerals, of course, have long mattered. Even during the Second World War, the island was valued as an important source of cryolite, a rare mineral used in the reduction of aluminium, which was essential in US aircraft production.

The intended light-heartedness of the puerilely titled “Greenland Adventure” is, I suspect, owing to Major Corey Ford, although he is credited with writing that section of War Below Zero jointly with Colonel Bernt Balchen, a Norwegian-born US aviator in charge of supervising the construction of a US air base in Greenland that he subsequently commanded.

The first-person narration is confusing. Just whose views does “Greenland Adventure” reflect? Ford’s or Balchen’s? According to the blurb on the dust jacket, the

idea of their literary collaboration came to Colonel Balchen and Major Ford at breakfast one cold day in an Iceland officers’ club with the strange name of Hotel de Gink. Over a dish of powdered eggs they decided that many Americans might like to know more about Greenland and [its] role in the present war […].

Another literary figure of note to contribute to War Below Zero was (Major) Oliver La Farge, an anthropologist whose novel about life in Navajo territory, Laughing Boy (1929), was awarded a Pulitzer Prize.

It was Ford, though, who had kept them laughing even when the general mood was somber with Depression-era books such as the Philo Vance parody, The John Riddell Murder Case (1930), “John Riddell” being a penname Ford used in the 1930s. The volume was illustrated by Ford’s frequent collaborator, the Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubia. For Vanity Fair, the pair created a series of “impossible interviews,” of which “Herr Adolf Hitler and Huey S. (“Hooey”) Long versus Josef Stalin and Benito Mussolini” (June 1933) strikes me as most deserving of an update.

Although Ford was more widely known as a wit whose friends included members of the Algonquin Round Table, War Below Zero was by no means an outlier in his career. During the Second World war, Ford also wrote Short Cut to Tokyo: The Battle for the Aleutians (1943).

Like War Below Zero, it was dramatized for radio, while Cloak and Dagger: The Secret Story of OSS (1946), an account of the wartime operations of the Office of Strategic Services that Ford, by then Lieutenant colonel, wrote in collaboration with Alastair MacBain, was turned into a radio series as well as being adapted for motion pictures. Ford introduced the first episode of Cloak and Dagger, broadcast on 7 May 1950, in his own voice.

Meanwhile, the on-air impression of War below Zero aired as part of the series Words at War on 18 July 1944, exactly six weeks after D-Day. By then, the tide had decidedly turned in favor of the allies, to use a word now under threat of extinction.

While the climate is argued to be the Army Air Forces’ most formidable adversary, it is the presence of the Germans on Greenland that provides the raison d’être for the US “mission” there.

A translated note by the Commandant of the German Wehrmacht Detail in Eskimonaes, dated 24 March 1943, serves to demonstrate the rationale and tactics of the enemy that had just attacked a Danish base in the northeast:

The USA protects its defense interests here in Greenland. We do the same also. We are not at war with Denmark. But the administration on Greenland gave orders to capture or shoot us, and besides that you gave weather reports to the enemy. You are making Greenland into a place of war. We have stayed quietly at our posts without attacking you. Now you want war, so you shall have war. But remember that if you shoot with illegal weapons (dum-dum bullets) which you have at hand here in the loft of the radio station, then you must take full responsibility for the consequences, because you are placing yourselves outside the rules of war.

“Greenland Adventure” concludes with the remark that the “Battle” for the island was

an important war, for the knowledge of the Arctic that we gained, at the cost of these men who gave their lives on the Ice Cap, will insure the safety of tomorrow’s aerial travel in the North. The bases and weather stations they fought to maintain, amid the darkness and silence and cold, will be future stops along the new air route to Europe.

Dated though War Below Zero is as an historical narrative, “Greenland Adventure” ventures to anticipate a future for the territory and predict its continued importance to the US:

Some day our whole conception of geography will be changed; the earth itself will be rolled over on its side, and the spindle of the globe will run, not from Pole to Pole, but from one side of the Equator to the other. Then the Arctic will be the very center of our new world; and across Greenland and northern Canada and Alaska will run the commercial airways from New York to London, from San Francisco to Moscow to India. Today’s highway of war will be tomorrow’s avenue of peace.

In the months leading to the 2026 World Economic Forum, much of the rest of the world did indeed appear to have “rolled over on its side,” even though US assertions as to its impending “civilizational erasure” may be premature. Not so the erasure of established alliances, Nato foremost among them.

The Arctic was argued to be once again the “center” of a “new world,” a focal point for a “new world” order, its newness being an elevated level of hubristic recklessness. White House rhetoric, if indeed Number 1947’s incoherent weaves warrant the term, made the hoped-for “avenue of peace” sound once again like an autobahn of war.

As the 2025 rebranding of the US Department of Defense—now the Department of War—made plain, the “Battle for Greenland” is on again. It is characteristic of the current administration’s zero tolerance for diplomacy, humanity and reason in an artificially manipulated volatile atmosphere that is increasingly difficult to forecast.

In lieu of a demonstrable enemy presence, the US now fabricates threats to justify its “mission” to occupy, seize and annex foreign lands, to sink ships, as well as to quell the spirit of constitutionally protected opposition in its own territory, determined to assume the part and posture of Nazi Germany.

Instead of waiting for the publication of another War Below Zero, and for a US President to plant an American flag on Greenland, fastidiously or otherwise, many former allies seem to have drawn a line in the snow. Exasperated by a playground bully’s assaults, they are clearing the ice for an “avenue of peace” founded in trade, mutual respect and, China’s eyes on Taiwan notwithstanding, cautious optimism.

After all, what are our survivable alternatives? To regard foreign territory as a “piece of ice” means putting on ice any dream we may still harbor of world peace. Whether we are faced with a war below zero or below water, it is the global climate we have created that now demands us to set aside all other “missions” and engage in dialogue previously thought “impossible.”

Discover more from Harry Heuser

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.