“What’s your great online discovery,” an interviewer asked Marcia Warren, star of the current West End production of Ladykillers. To this, the veteran of stage, screen and radio replied, “What does online mean?” It is just the kind of answer most of us expect—and want to hear—from someone past middle age, which makes hers such a sly response. Warren remains in character, as Mrs. Wilberforce, kindly old landlady to the killers, giving us what we find so reassuring and endearing about the senescence we otherwise dread. She may or may not be joking—but she sure has earned the right neither to know nor to care. Looked at it that way, being past it becomes a shelter, a retreat beyond trends, updates and upgrades whose seeming simplicity appeals to those who cannot afford to be quite so nonchalant about technology, who feel the pressure of performing in and conforming to the construct of the present as a digital age.

Not to know or willfully to ignore—what luxury! Young and not-so-young alike find comfort in this deflecting mirror image of our future selves. It’s a Betty White lie we use to kid ourselves .

We enjoy making light of old age; and those of us who have half a conscience enjoy it even more to be presented with elderly people or characters who are not simply the brunt of yet another ageist joke but are in on it—and cashing in on it as well. We laugh all the way as they take our laughter to the bank.

We want older folks to be feisty because it comforts us to know that, even in our declining years, there are weapons left with which to fight, however futile the fighting. The middle aged, by comparison, are past the prime against which the standard their looks and performances are measured; it is their struggle to conceal or deny this obsolescence that makes them the stuff of deflationary humor. We don’t laugh at Mrs. Wilberforce; we laugh at the bumbling crooks whose willfulness is no match for her force shield of insuperable antiquity.

It is this nod to nostalgia as a weapon against the onslaught of modernity that makes Ladykillers such a charmer of a story. And what makes it work on the stage just as it works on the screen is that the 1955 original requires no update: the Ladykillers was born nostalgic. It hit the screens—in fabulous Technicolor, no less—at a time when, after years of postwar austerity, the British were ready to look back in amusement at their wants and desires and all those surreptitious attempts to meet them. Sneers turned to smiles again as greed was finally being catered to once more.

Eluding those who try to will it by force, fortune winks at those who wait like Mrs. Wilberforce, a senior citizen yet hale, clearheaded and driven enough to enjoy a sudden windfall. It is a conservative fantasy that appealed then as it appeals now, especially to middleclass, middle-aged theatergoers eager to distract themselves from banking woes and pension fears, from cybercrime and urban riots.

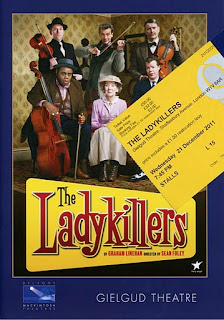

Familiar to me from radio dramatics, Warren’s name was the only one on the marquee I recognized as I decided whether or not take in what I assumed to be another one of those makeshift theatricals that too often take the place of real theater these days—stage adaptations of popular movies, books and cartoons like Shrek, Spider-Man, or Addams Family with which the theater world is trying rather desperately to augment its aging audience base.

Written by Graham Linehan and directed by Sean Foley, this new production of The Ladykillers fully justified its staging. There is much for the eye to take in; indeed, it owing to an able cast—and the lovely, lively Ms. Warren above all— to prevent the ingenious set and special effects from stealing this caper.

In the real, honest-to-goodness make-believe beyond the online trappings of which she claims to be ignorant, Warren gives us just what we want. After all, acting for our pleasure and acting out our desires is her business. It’s the oldest profession in the world.

There would have been no soap—and no soap operas—if we didn’t have trepidations about not being quite fresh, anxieties that were over-ripe for commercial exploitation. In the US, tuners-in of the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s were constantly being alerted to the dangers of B-O, reminded to ‘Lux’ their ‘dainties,’ and told to gargle before putting their kissers to the test. Lest they could endure facing guilt by omission, listeners lathered up with products like White King toilet soap, the box tops of which they collected and sent in to broadcasters as ocular proof of their hygienic diligence, for which cumulative evidence they were duly awarded various prizes (or premiums).

There would have been no soap—and no soap operas—if we didn’t have trepidations about not being quite fresh, anxieties that were over-ripe for commercial exploitation. In the US, tuners-in of the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s were constantly being alerted to the dangers of B-O, reminded to ‘Lux’ their ‘dainties,’ and told to gargle before putting their kissers to the test. Lest they could endure facing guilt by omission, listeners lathered up with products like White King toilet soap, the box tops of which they collected and sent in to broadcasters as ocular proof of their hygienic diligence, for which cumulative evidence they were duly awarded various prizes (or premiums).