Well, it rolled into town last night . . . and carted me right back to high school (in Germany, anno never-mind), where I was exposed to it first. The National Theatre’s “education mobile,” I mean, whose production of Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle I went to see at the local Arts Centre. Despite the publicly staged custody battle at the Circle‘s center, I did not once think of the circus that has become the life and legacy of Anna Nicole Smith. Brecht’s parables of the filthy rich and dirt poor are hardly without tabloid appeal; but instead of drawing parallels between this story and history, I felt encouraged by the production’s interpretation of Brecht’s theory of Epic Theater to contrast the techniques of the theatrical stage with the potentialities of the sound stage, radio being a medium of which Brecht was suspicious at first (given its exploitation in Fascist Germany), but for which he was to write a number of plays.

Well, it rolled into town last night . . . and carted me right back to high school (in Germany, anno never-mind), where I was exposed to it first. The National Theatre’s “education mobile,” I mean, whose production of Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle I went to see at the local Arts Centre. Despite the publicly staged custody battle at the Circle‘s center, I did not once think of the circus that has become the life and legacy of Anna Nicole Smith. Brecht’s parables of the filthy rich and dirt poor are hardly without tabloid appeal; but instead of drawing parallels between this story and history, I felt encouraged by the production’s interpretation of Brecht’s theory of Epic Theater to contrast the techniques of the theatrical stage with the potentialities of the sound stage, radio being a medium of which Brecht was suspicious at first (given its exploitation in Fascist Germany), but for which he was to write a number of plays.

Communism has always been big business in capitalist societies, both as fuel for wars, cold or otherwise, and as an artistic construct. A carnivalesque appreciation of his anti-capitalist allegories from the comfort of a loge might run counter to anything Brecht envisioned in his organon, but I suspect that such is the spirit in which most audiences take in his works for the stage. They are didactic, all right, but that does not mean theatergoers are ready, willing, or able to be instructed.

Instead, audiences might take in, take on or leave Brecht’s Epic theatricals, only to return to their shopping, to the latest installment of an American television serial featuring the works of Hollywood’s highest-paid plastic surgeons, or to their various modes of right-winging it in style. Episches Theater struggles against the complacency induced by the convenience and relative comforts of a reserved seat in a handsome theater. Theatergoing, after all, is little more than a costly interlude these days, a getting-away-from the everyday rather than a forum in which to face it.

Besides, Brecht’s apparatus seems by now more creaky than a well-oiled Victorian spectacle. Its stage was not the proscenium arch of melodrama, plays of sentiment and sensation that draw you in and, once the curtain is drawn, absolve you from any responsibility to engage further with whatever you had the privilege of witnessing. Never mind that The Caucasian Chalk Circle draws to a close with the potentially high-tension climax of two women called upon to tear at a child rightfully belonging to one of them (the verdict depending on the judge’s—and our—definition of “rightful”). Much lies outside this circle that invites onlookers to stray from the center.

The main principle of Epic Theater is not to let anyone watching get emotionally absorbed in the action. Brechtian drama challenges audiences to observe behavior, action and circumstance, however stylized, in order to assess and draw conclusions from it. Conceived as a theater of estrangement (or Verfremdung), it is meant to provoke thought rather than pity. The play (and the play within) remain an artifice rather than becoming—or assuming the guise of—reality.

In order to create this sense of estrangement, the National Theatre production lets the audience in on the stagecraft involved in the manufacture of realist theater, especially the motion picture variety whose special effects trickery has long surpassed traditional stagecraft. The stage was both scene and soundstage, a set peopled with foley (or sound effects) artists at work in the background and, to highten the effect of alienation, interacting with the performers or taking part in the drama they help to mount. Not since I last attended a production of a radio drama have I seen so many tricks of the trade displayed, from the production of a crackling fire to the imitation of a bawling infant.

I’m not sure whether Brecht would have approved of this interpretation of his theory, which results in a spectacle that was amusing rather than authoritative, a Marx Brother’s production during Karl’s night off, a staging that turned Verfremdungseffekt into an elaborate running joke. This Chalk Circle, replete with a narrator addressing the audience with a microphone in his hand, was a radio melodrama turned “epic” by virtue of being both played and displayed.

On the air, with its techniques obscured from view, it would have come across like the very stuff against which Brecht rebelled with his theory. The eye and the ear were pitted against each other, an “epic” battle of the senses whose enemy is realism but whose victim is engagement. For once, my ears were the channels of realism, while my eyes were instructed to see and disbelieve. Sure, I learned how to set a palace on fire; but Revolution had nothing to do with it.

It can do serious damage to one’s sensibilities. Popular culture, I mean. I sensed its deadening force tonight when I attended a screening of Jean Cocteau’s first film, Le sang d’un poète (1930). It was shown, together with the Rene Clair short Entr’acte (1924), at the National Library of Wales here in Aberystwyth, where it was presented with live musical accompaniment by composer Charlie Barber, who also conducted. However animated the score, the images left me almost entirely cold. Why? I wondered.

It can do serious damage to one’s sensibilities. Popular culture, I mean. I sensed its deadening force tonight when I attended a screening of Jean Cocteau’s first film, Le sang d’un poète (1930). It was shown, together with the Rene Clair short Entr’acte (1924), at the National Library of Wales here in Aberystwyth, where it was presented with live musical accompaniment by composer Charlie Barber, who also conducted. However animated the score, the images left me almost entirely cold. Why? I wondered.

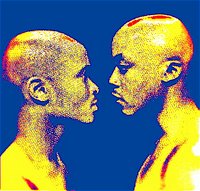

Chicken pox. That’s what had kept the Johannesburg Market Theatre players from coming down to Cardigan Bay to perform in Athol Fugard’s The Island. Last night, the two (Mpho Osei-Tutu as Winston and Thami Mngqolo as John) made up for it, even though their audience (students at the local university) had taken off by then for some holiday destination. It was worthwhile hanging on to the ticket, though. And since I enjoy debating myself, I dug up an old college paper I had written on The Island for a graduate course in drama back in the mid-1990s. Aside from its title “Carrion Antigone,” that essay, while not outright dismissed by its academic audience, is rather too slight a performance to warrant reproduction here. It told me more about myself than the play, which I argued to be less concerned with historical facts than with cultural universals.

Chicken pox. That’s what had kept the Johannesburg Market Theatre players from coming down to Cardigan Bay to perform in Athol Fugard’s The Island. Last night, the two (Mpho Osei-Tutu as Winston and Thami Mngqolo as John) made up for it, even though their audience (students at the local university) had taken off by then for some holiday destination. It was worthwhile hanging on to the ticket, though. And since I enjoy debating myself, I dug up an old college paper I had written on The Island for a graduate course in drama back in the mid-1990s. Aside from its title “Carrion Antigone,” that essay, while not outright dismissed by its academic audience, is rather too slight a performance to warrant reproduction here. It told me more about myself than the play, which I argued to be less concerned with historical facts than with cultural universals. The beleaguered sun appeared to have triumphed at last in a narrow victory over the long-reigning clouds, and I, a much deprived heliolater, ventured out with laptop and deckchair to luxuriate in the vernal cool of a brightly colored afternoon, absorbed in thoughts of . . . death, dread, and desolation. It was not the long shadows cast upon the weeds-corrupted lawn, nor the shrieking of the crows nesting in our chimney that evoked such gloomy visions; nor was it the realization that the skies were darkening once more as another curtain of mist was lowering itself upon the formerly glorious outdoors.

The beleaguered sun appeared to have triumphed at last in a narrow victory over the long-reigning clouds, and I, a much deprived heliolater, ventured out with laptop and deckchair to luxuriate in the vernal cool of a brightly colored afternoon, absorbed in thoughts of . . . death, dread, and desolation. It was not the long shadows cast upon the weeds-corrupted lawn, nor the shrieking of the crows nesting in our chimney that evoked such gloomy visions; nor was it the realization that the skies were darkening once more as another curtain of mist was lowering itself upon the formerly glorious outdoors. Moving from Manhattan to Mid-Wales was bound to lower my chances of taking in some live theater now and then (not that Broadway ticket prices had allowed me to keep the intervals between “now” and “then” quite as short as I’d like them to be). I expected there’d be the odd staging of Hamlet with an all-chicken cast or a revival of “Hey, That’s My Tractor” (to borrow some St. Olaf stories from The Golden Girls). Luckily, I’m not one to embrace the newfangled and my tastes in theatrical entertainments are, well, conservative. I say luckily because even if you’’re living west of England rather than the West End of its capital, chances are that there’s a touring company coming your way, eventually.

Moving from Manhattan to Mid-Wales was bound to lower my chances of taking in some live theater now and then (not that Broadway ticket prices had allowed me to keep the intervals between “now” and “then” quite as short as I’d like them to be). I expected there’d be the odd staging of Hamlet with an all-chicken cast or a revival of “Hey, That’s My Tractor” (to borrow some St. Olaf stories from The Golden Girls). Luckily, I’m not one to embrace the newfangled and my tastes in theatrical entertainments are, well, conservative. I say luckily because even if you’’re living west of England rather than the West End of its capital, chances are that there’s a touring company coming your way, eventually.