When a good friend of mine told me earlier this week that comic strip reporter Tintin had been “outed” by a fellow journalist, I was not the least bit surprised. The Tinky Winky controversy of the late-1990s came to mind, in which Jerry Falwell—discard his soul!—denounced the handbag-clutching purple creature of Teletubbies fame as being a “gay role model” for television’s newest and youngest target audience, the toddler. As if, with parents plonking them down in front of the box at that age, those poor impressionables did not have enough worries about their future already.

When a good friend of mine told me earlier this week that comic strip reporter Tintin had been “outed” by a fellow journalist, I was not the least bit surprised. The Tinky Winky controversy of the late-1990s came to mind, in which Jerry Falwell—discard his soul!—denounced the handbag-clutching purple creature of Teletubbies fame as being a “gay role model” for television’s newest and youngest target audience, the toddler. As if, with parents plonking them down in front of the box at that age, those poor impressionables did not have enough worries about their future already.

Now, Matthew Parris, who purports to know the Belgian reporter more intimately than anyone except Snowy, had no such agenda; that is, he did not equate “gay” with “dangerous.” Still, I would not be so presumptuous as to drag the perennially adolescent Tintin, who turns 80 today, into what some assume to be a camp (well, it can be camp, as I demonstrated here). Instead, I did a little outing myself by dragging the above sculpture, my most recent addition to a small collection of Tintin memorabilia, onto our patio, whereupon I took in the animated Secret of the Unicorn, based on the strip rumored to be the source for Steven Spielberg’s Tintin project now in pre-production.

I don’t suppose that the gossip about Hergé’s boy will in any way affect the box-office chances of the film and its intended sequels, about the success of which there has been so much doubt already that it was slow in receiving the green light. After all, if one source is to be believed, Tintin enthusiasm in the US and Britain amounts to “little more than a cult.” However unfortunate the phrase in this overstatement, nothing sinister or questionable other than doubt about the figure’s bankability is implied. Still, the boy reporter, who has a somewhat shady past in propagandist cartoons and only gradually matured into the open-minded, worldly youth he became in his Tibetan adventure (the stage version of which I discussed here), has had his share of detractors.

Warning labels other than “Caution: content may damage your kid’s chances to turn out straight” have been attached to Tintin’s exploits in the Congo (as mentioned here), and his tendencies have been denounced as right-wing. A globetrotting reporter who is racist, fascist, and gay? A rather incongruous picture; but then, the Tintin of 1929 is not the same young man who cleared the gypsies accused of having stolen the Castafiore emerald in 1963.

When first I encountered Tintin, no such thoughts occurred to me. Still, in part for reasons made plain by Mr. Parris, I was intrigued by the cub reporter and his freedom to travel around the world, unencumbered by homework, filial duties, or anxieties about puberty. He was as exciting and comforting in this respect as Pippi Longstocking, only neater and more mature.

As an adventure-starved, working-class latchkey kid unsure and downright scared about his own sexuality, I was only too eager to relate to an independent teenager whose parents are never seen or talked about, who does not appear to have girls on his mind, whose closest human pal is a hunk of a sea captain, and who is devoted to a fluffy pet dog named Snowy. I guess that makes me whatever Mr. Parris just labeled him.

When I now add another label in honor of Tintin’s birthday, realizing just how often the lad has found his way into this journal, it simply reads . . . Tintin.

Placing Mitchell Leisen alongside Hollywood’s top flight directors is likely to raise eyebrows among those whose brows are already well elevated. Most others will simply shrug their cold shoulders in“Who he? indifference, a stance with which I, whose shoulders are wont to brush against the dusty shelves and musty vaults of popular culture, am thoroughly familiar by now. Respected for his knack of striking box-office gold but dismissed by his peers, the former art director was not among the auteurs whose works are read as art chiefly because it is easier to conceive of artistic expression as a non-collective achievement: something that bears the clearly distinguishable signature of a single individual. Their careful design aside, little seems to bespeak the Leisen touch, which is as light as it is assured. Stylish and slick in the best Paramount tradition, a Leisen picture stunningly sets the stage under the pretense of drama; otherwise, it has few pretensions.

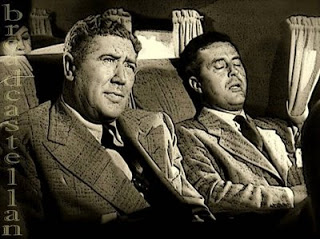

Placing Mitchell Leisen alongside Hollywood’s top flight directors is likely to raise eyebrows among those whose brows are already well elevated. Most others will simply shrug their cold shoulders in“Who he? indifference, a stance with which I, whose shoulders are wont to brush against the dusty shelves and musty vaults of popular culture, am thoroughly familiar by now. Respected for his knack of striking box-office gold but dismissed by his peers, the former art director was not among the auteurs whose works are read as art chiefly because it is easier to conceive of artistic expression as a non-collective achievement: something that bears the clearly distinguishable signature of a single individual. Their careful design aside, little seems to bespeak the Leisen touch, which is as light as it is assured. Stylish and slick in the best Paramount tradition, a Leisen picture stunningly sets the stage under the pretense of drama; otherwise, it has few pretensions. Leisen was not about to denounce the medium he had romanced in two of his earlier revues, The Big Broadcast of 1937 and its 1938 follow-up. Instead, Golden Earrings confronts nationalistic, state-run radio with a distinctly American voice of commercial broadcasting. In the narrative frame, the English officer is seen relating his story to Quentin Reynolds (pictured here with Milland), a news commentator known for his on-air missives to Doktor Goebbels and Herr Schickelgruber.

Leisen was not about to denounce the medium he had romanced in two of his earlier revues, The Big Broadcast of 1937 and its 1938 follow-up. Instead, Golden Earrings confronts nationalistic, state-run radio with a distinctly American voice of commercial broadcasting. In the narrative frame, the English officer is seen relating his story to Quentin Reynolds (pictured here with Milland), a news commentator known for his on-air missives to Doktor Goebbels and Herr Schickelgruber.

,+Low+Fidelity.jpg)