“So, here he is. My father. In a churchyard in the furthest tip of Llŷn. Eighty years old. Wild hair blowing in the wind. Overcoat that could belong to a tramp. Face like something hewn out of stone, staring into the distance.” The man observing is Gwydion, the middle-aged son of R. S. Thomas (1913-2000)—“Poet. Priest. Birdwatcher. Scourge of the English. The Ogre of Wales.” With this terse description opens Neil McKay’s “Alone Together,” a radio play first aired last Sunday on BBC Radio 3 (and available online until 28 March).

“So, here he is. My father. In a churchyard in the furthest tip of Llŷn. Eighty years old. Wild hair blowing in the wind. Overcoat that could belong to a tramp. Face like something hewn out of stone, staring into the distance.” The man observing is Gwydion, the middle-aged son of R. S. Thomas (1913-2000)—“Poet. Priest. Birdwatcher. Scourge of the English. The Ogre of Wales.” With this terse description opens Neil McKay’s “Alone Together,” a radio play first aired last Sunday on BBC Radio 3 (and available online until 28 March).

The voice of the Nobel Prize nominated poet (as portrayed by Jonathan Pryce) is heard reading lines from his works, the words that are, to us, a stand-in for the man. None of them escape the commentary of his estranged son: “Yes, you could tell yourself this is him, the real R. S. Thomas,” the observer, filial yet unloving, remarks. “But you’d be entirely wrong.” As his father’s old voice keeps on reciting, he adds: “Oh, he’d be happy enough for you to fall for it . . . and to fall for the version he tells of his own life.”

What compels the son to revise this “version” of a life is the life of another, a figure that, to his mind, is concealed or mispresented in the autobiography of the father. The figure is Elsi, the Welsh poet’s English wife (1909-1991), whose fifty-year-relationship with R. S. was compressed by him in these lines:

She was young;

I kissed with my eyes

closed and opened

them on her wrinkles.

Speaking of their first encounter, R. S. introduces Elsi as “a girl who was lodging fairly close by,” the kind of icy understatement with which Thomas, writing about himself in the third person, kept his distance from his readers, just as the people he knew and wrote about were turned into abstracts on a page. “He doesn’t even give her a name,” the son comments, “and that’s where it starts to unravel.”

The churchyard in which we are introduced to the father is Elsi’s burial place; it is Gwydion’s ambition and quest to bring her to life for us, to let us see her in something other than the austere words of an introverted, discontented, and tormented man—an Anglican rector who sought isolation in the remote west of “the real Wales,” who, advocating Welsh independence and separation from England, was consumed by what the Welsh call “Hiraeth”: a longing for home. In how far did this longing, this radical yet futile attempt at forging an identity alien to him, prevent R. S. from making a home for the two, the three, of them?

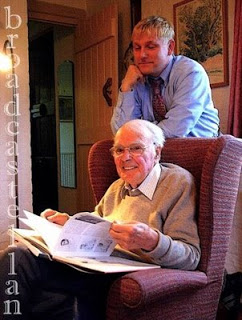

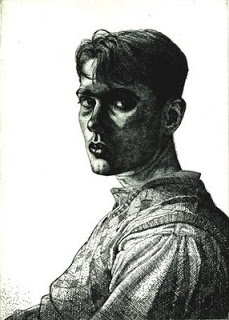

Searing, severe, yet profoundly moving, “Alone Together” is a compelling play at biography; listening to it, I was reminded of the above self-portrait of Elsi, who, as an artist, was known as Mildred Eldridge, respected and sought-after long before R. S. published a line of poetry. Until now, whenever I looked at it, hanging there on a wall of our home, I have never considered it as an autobiographical act.

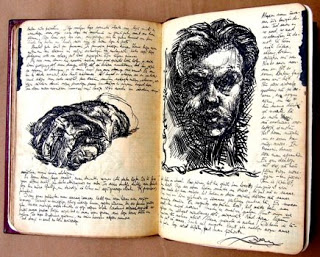

Both their approaches to rendering the self seem indirect, his being the third person singular, hers a reflection. Eldridge does not assume the center of the frame; nor does she give us a close-up of the face in the looking-glass; and yet, her self-portrait, tentative as it may be, allows us a glimpse at her perception. The distant self in her husband’s performance, by comparison, seems a construct, the artifice of an entire controlled performance. Unlike her husband, Eldridge appears before us the first person singular, letting us see her as only she sees herself: a mirror image.

In how far are written or spoken words a path to—or a vessel for—the essence of the one writing or speaking? Is anyone knowable through the vocables that are a locum for self and experience? Cautioned not to take a father’s word for whatever “it” amounts to verity, can we now trust the estranged son in his voice-over, his over-writing of the words he claims to be false or misleading?

“Alone Together” suggests that, for all his accomplishments as a writer, R. S. Thomas—who yearned to be Welsh but could not speak it, who, as Elsi puts it, “adopted the vowels of an Oxford Don” to hide the shame of being, as he puts it, an “ignorant Taff from Cardiff”—envied the ease with which his accomplished artist wife communicated in a language beyond words, expressed herself freely on a blank canvas . . . and felt at home there.

Has my ear been giving me the evil eye? For weeks now, I have been sightseeing and snapping pictures. I have seen a few shows (to be reviewed here in whatever the fullness of time might be), caught up with old friends I hadn’t laid eyes on in years, or simply watched the world coming to New York go by—all the while ignoring what I set out to do in this journal; that is, to insist on equal opportunity for the ear as channel through which to take in dramatic performances so often thought of requiring visuals. When. in passing, I came across this message on the facade of the Whitney Museum, my mind’s eye kept rereading what seems to be such a common phrase” “As far as the eye can see.”

Has my ear been giving me the evil eye? For weeks now, I have been sightseeing and snapping pictures. I have seen a few shows (to be reviewed here in whatever the fullness of time might be), caught up with old friends I hadn’t laid eyes on in years, or simply watched the world coming to New York go by—all the while ignoring what I set out to do in this journal; that is, to insist on equal opportunity for the ear as channel through which to take in dramatic performances so often thought of requiring visuals. When. in passing, I came across this message on the facade of the Whitney Museum, my mind’s eye kept rereading what seems to be such a common phrase” “As far as the eye can see.”

Well, New York City is looking more festive than ever, “ever” starting from the first Christmas I spent here back in 1989. There are outdoor markets on Union Square and Bryant Park, and a holiday fair at Grant Central Station. A departure from the city’s traditional Christmas windows, to say the least, was the above installation at the Lever House on Park Avenue in midtown Manhattan. I recall a Christmas carousel in the window; but this year, there was something else on display that is sure to make your head (and possibly your stomach) turn.

Well, New York City is looking more festive than ever, “ever” starting from the first Christmas I spent here back in 1989. There are outdoor markets on Union Square and Bryant Park, and a holiday fair at Grant Central Station. A departure from the city’s traditional Christmas windows, to say the least, was the above installation at the Lever House on Park Avenue in midtown Manhattan. I recall a Christmas carousel in the window; but this year, there was something else on display that is sure to make your head (and possibly your stomach) turn.