“Will radio writing always be in demand? What will television do to radio writing? Why should anyone learn a new technique in writing when some unexpected development might wipe out the demand for this sort of work almost overnight? Is radio broadcasting basically sound? Will it endure and develop?” Such is the battery of questions with which readers eager for pointers on How to Write for Radio were being confronted upon opening one of the earliest books on the subject. The co-author of this 1931 manual, Katharine Seymour, was an accomplished radio playwright whose work was heard on prestigious programs such as Cavalcade of America. On this day, 12 January 1941, Seymour talked to announcer Graham McNamee about her experience entering the broadcasting business in the mid-1920s, back when it bore little resemblance to the confident, respected, and efficient medium it had become by the late 1930s, by which time Seymour had co-written another book on Practical Radio Writing.

“Will radio writing always be in demand? What will television do to radio writing? Why should anyone learn a new technique in writing when some unexpected development might wipe out the demand for this sort of work almost overnight? Is radio broadcasting basically sound? Will it endure and develop?” Such is the battery of questions with which readers eager for pointers on How to Write for Radio were being confronted upon opening one of the earliest books on the subject. The co-author of this 1931 manual, Katharine Seymour, was an accomplished radio playwright whose work was heard on prestigious programs such as Cavalcade of America. On this day, 12 January 1941, Seymour talked to announcer Graham McNamee about her experience entering the broadcasting business in the mid-1920s, back when it bore little resemblance to the confident, respected, and efficient medium it had become by the late 1930s, by which time Seymour had co-written another book on Practical Radio Writing.

Many such how-to guides followed throughout the 1940s, a testament to the vastness of the industry, its demand for written words and for talent familiar with the codes and regulations to which they were expected to adhere. In the 1920s, when Seymour tried to promote herself from typist to writer, she was told by her boss at WEAF, New York, that “no radio station will ever need more than one script writer,” to which shortsighted remark McNamee, himself one of the old-timers, responded with a resounding “Wow!”

The days of largely unchecked improvisation were over. Being obliged to keep their word, broadcasters had learned that the spoken word needed to become copy (that is, text) and that every dramatic dialogue had to be played by the book the FCC would otherwise throw at them.

One of the latest addition to my library, Albert R. Crews’s Professional Radio Writing (1946), acquainted readers with what was known as the NAB code. As the author, then production director at NBC, explained, the code was a measure of self-censorship undertaken by the National Association of Broadcasters and adopted on 11 July 1939 to outline the “handling of children’s programming, controversial public issues, educational programming, news, [and] religious broadcasts,” as well as to set down the “acceptable length of commercial copy and its content.”

In keeping with this code, the National Broadcasting Company developed its own guidelines for “continuity acceptance,” “continuity” being anything read on the air. Anyone learning how to write radio drama with the view of hearing it produced had to keep in mind, for instance, that “[w]hite slavery, sex perversion or the implication of it may not be treated in NBC programs” and that the “fact of marriage must never be used for the introduction of scenes of passion excessive or lustful in character, or which are clearly unessential to the plot development.”

In the treatment of crime, the “use of horrifying sound effects as such” was “forbidden.” According to the code, no character was to “be depicted in death agonies,” nor could the “death of any character be presented in any manner shocking to the sensibilities of the public.” The very “mention of intoxicants” had to “be held to a minimum” and “suggestive dialogue and double meaning” was “never [to] be used.”

Responding to the hullaballoo over CBS’s “War of the Worlds” broadcast, NBC also stipulated that

[f]ictional events shall not be presented in the form of authentic news announcements. Likewise, no program or commercial announcement will be allowed to be presented as a news broadcast using sound effects and terminology associated with news broadcasts. For example, the use of the word “Flash!” is reserved for the announcement of special news bulletins exclusively, and may not be used for any other purpose except in rare cases where by reason of the manner in which it is used no possible confusion may result.

Was it any wonder that, as Crews put it, there had been a “tendency on the part of many outstanding writers in [the US] to scoff at radio as a possible medium for their talents”? Such talent-repelling strictures notwithstanding, he found it “heartening” to note just

how many writers of importance radio has itself created. There are dozens of highly skilled dramatic writers who are, for the most part, completely unknown to the public, but who each day do distinguished work in their field. The anonymity of such writers is no measure of their skill or their success.

It is with the efforts of those mostly unheard of and almost entirely forgotten writers that I shall continue to concern myself in this journal; writers who skillfully interpreted the code and somehow managed to subvert it, or who at least found leeway for play “within the limits” set down for them; writers whose works, to take up one of Seymour’s questions, have endured in recordings even if American radio drama, as an art, has largely ceased to develop further.

Having lost their purpose as instruction manuals for an essentially defunct business, books like Professional Radio Writing nonetheless instruct us how to read the plays that went on the air, to account for their limitations and appreciate their qualities.

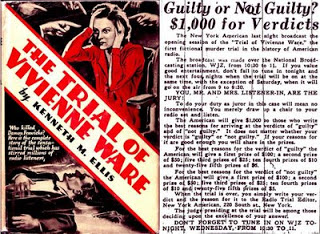

“It does not matter whether your verdict is ‘guilty’ or ‘not guilty.’ If your reasons for it are good enough you will share in the prizes.” With this peculiar invitation, millions of US Americans were lured to their radios, tuned in to WJZ, for a trial in which they, the listening public, were called upon to act as jurors. As previously mentioned here,

“It does not matter whether your verdict is ‘guilty’ or ‘not guilty.’ If your reasons for it are good enough you will share in the prizes.” With this peculiar invitation, millions of US Americans were lured to their radios, tuned in to WJZ, for a trial in which they, the listening public, were called upon to act as jurors. As previously mentioned here,

“I don’t have much respect for biographers,” I once told John N. Hall, noted author of Trollope: A Biography and Max Beerbohm: A Kind of Life. I was being mischievous, knowing my professor to have a sense of humor that makes him just the man to examine the lives and fictions of the humorists who attract him. Indeed, I have rarely met an academic whose mentality was better suited to his subjects. I was not merely being facetious, though. I was also being honest. I don’t read biographies; not cover to cover, at least. I am too impatient to go through a series of incidents designed to trace the traits and career of a famous so-and-so to great-grandparents who were semi-literate peasants from Eastern Europe, to illustrate what impact the childhood agony of losing a balloon during a rainstorm had on an artist’s psyche, or explain what it really means to be a supposed nobody before becoming an alleged somebody.

“I don’t have much respect for biographers,” I once told John N. Hall, noted author of Trollope: A Biography and Max Beerbohm: A Kind of Life. I was being mischievous, knowing my professor to have a sense of humor that makes him just the man to examine the lives and fictions of the humorists who attract him. Indeed, I have rarely met an academic whose mentality was better suited to his subjects. I was not merely being facetious, though. I was also being honest. I don’t read biographies; not cover to cover, at least. I am too impatient to go through a series of incidents designed to trace the traits and career of a famous so-and-so to great-grandparents who were semi-literate peasants from Eastern Europe, to illustrate what impact the childhood agony of losing a balloon during a rainstorm had on an artist’s psyche, or explain what it really means to be a supposed nobody before becoming an alleged somebody. You might say that I am not easily impressed by facts and downright doubtful of them; that I am unconvinced a life can be told by means of sundry scraps of evidence culled from contemporary sources or the recollections of contemporaries whose lost marbles are dutifully dredged from the gully of memory lane. It’s all that; but I would like to think that respect has something to do with it as well—respect for a creative mind expressing itself in a work of art by someone who might not be willing or able to open up otherwise. In other words, I take what an artist is willing to give, even if the limited supply of such works are dictated, to some extent, by market demands.

You might say that I am not easily impressed by facts and downright doubtful of them; that I am unconvinced a life can be told by means of sundry scraps of evidence culled from contemporary sources or the recollections of contemporaries whose lost marbles are dutifully dredged from the gully of memory lane. It’s all that; but I would like to think that respect has something to do with it as well—respect for a creative mind expressing itself in a work of art by someone who might not be willing or able to open up otherwise. In other words, I take what an artist is willing to give, even if the limited supply of such works are dictated, to some extent, by market demands.