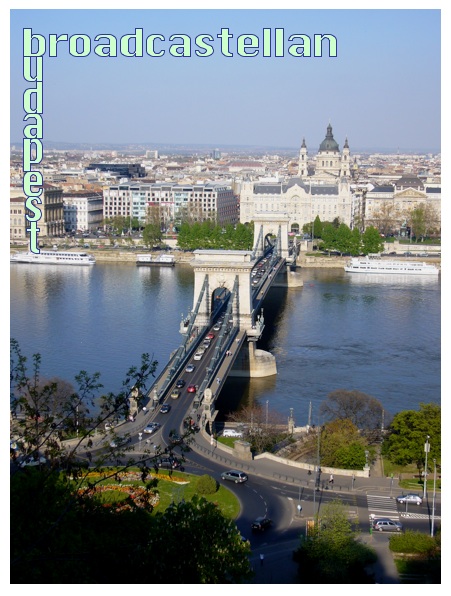

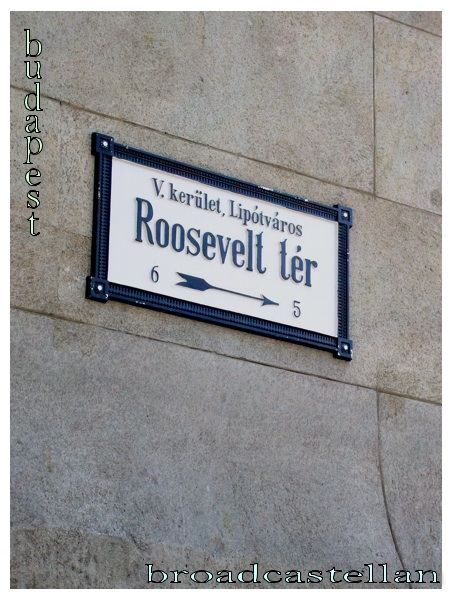

Considering that it is St. George’s Day (as well as the anniversary of the birth of the Bard), I am going to stay a little closer to home this time and, forgoing a return to Budapest, report instead on my audience with the Queen. Victoria Regina, I mean, whom last I captured towering over Birmingham’s German Christmas market (pictured) and imagined listening to her Electrophone. Yesterday, we went to An Evening with Queen Victoria, a one-woman show in which British stage, screen, and television actress Prunella Scales, accompanied by a lyric tenor and a pianist (who is also the husband of the play’s creator and director), has toured the new and old world, including England, Australia, Canada and the United States. So, it was bound to make it to Wales, eventually.

Just in time, I might add. Ms. Scales, whose life now spans as many decades as the play, was called upon to read, in character, selections from the queen’s published reminiscences (Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the Highland) and personal correspondences, from her youthful comments on her German cousins to her reflections on marriage and motherhood, duty, loss, and old age.

Along the way, the star struggled with some of her lines and had to be prompted audibly at one point (Fawlty Powers, I could not help thinking), while the aged pianist, who at one time loudly cleared his throat as if he had quite forgotten that there was a performance going on, played pieces of classical pieces by Rossini, Schumann, and Mendelssohn, which were interpreted with much feeling by the tenor, who thus painted himself into the queen’s portrait. The three of them joined forces to sing “Duties of a Monarch” from Gilbert and Sullivan’s Gondoliers:

Oh, philosophers may sing

Of the troubles of a King,

But of pleasures there are many and of worries there are none;

And the culminating pleasure

That we treasure beyond measure

Is the gratifying feeling that our duty has been done!

The whole royal affair might have faired well on radio, I thought, since it is largely a first-person narrative involving little action, aside from the queen’s efforts to rise from her easy chair to pick up various letters and books, to fetch a cane or wrap herself up as she gradually ages before us. I was not surprised, therefore, to learn that An Evening has indeed been produced for BBC radio.

It was on the air that the Her (Imperial) Majesty had been introduced into the living rooms of America, voiced by Helen Hayes, who inhabited the part on the Broadway stage in Laurence Housman’s Victoria Regina (1934), a play initially banned in England for daring to impersonate British royalty yet living.

An Evening was based largely on actual reminiscences of the monarch, as this somewhat unfortunate line from the leaflet that served as a playbill informed me: “The words of this programme are compiled entirely from Queen Victoria’s own journals and letters, together with some additional material from contemporary sources,” which is like saying that a loaf of bread is whole grain, except for a few preservatives and added flavors, natural or otherwise, however difficult to detect.

A similar claim was made by radio announcer Ernest Chapell, who introduced the 2 June 1939 broadcast of Orson Welles’s Campbell Playhouse by declaring that in order to “complete the true picture of this great queen, Mr. Welles has used still another source, one which only a few years ago was still a closed book, locked away in the official archives of the royal family: the personal diary of Queen Victoria.”

Containing the same material and creating a similar effect, An Evening is essentially a non-dramatic version of Victoria Regina, which Hayes revived once again for her Electric Theater on 14 November 1948, the day the queen’s great-great-great grandson, Prince Charles, was born. Intimate without being indiscreet, informal without being vulgar, both sketches create the quiet sensation of familiarity by bringing alive, in her own words, a woman who is more often thought of as an institution or the name crowning an era.

In an age favoring uncompromising exposés and compromising snapshots, close-ups with which we distance ourselves, such personal introductions are a charming and welcome illusion.

I appreciate a good hoax; and no hoax is any good unless it wrings from you the admission that you have been had. My common sense yields to the artistry of the con, the handiwork of cheeky tricksters who can cheat you out of your trousers by presenting you a with a hook from which to suspend your disbelief. And however desperately I might try to cover up and recover my composure by juggling an assortment of polysyllables, I am just the kind of fall guy you’d love to be around on April Fools’ Day—or any other day, if you are among those who practice their legerdemain without a license.

I appreciate a good hoax; and no hoax is any good unless it wrings from you the admission that you have been had. My common sense yields to the artistry of the con, the handiwork of cheeky tricksters who can cheat you out of your trousers by presenting you a with a hook from which to suspend your disbelief. And however desperately I might try to cover up and recover my composure by juggling an assortment of polysyllables, I am just the kind of fall guy you’d love to be around on April Fools’ Day—or any other day, if you are among those who practice their legerdemain without a license. No matter how hard I tried to make light of them, by pulling their fingers or sitting on their boots, the colossal statues gathered in the ideological leper colony that is

No matter how hard I tried to make light of them, by pulling their fingers or sitting on their boots, the colossal statues gathered in the ideological leper colony that is

It is the fuel that keeps the search engines humming. It is fodder for loudmouthed if often unintelligible webjournalists thriving on the divisive. It is the foundation of many a rashly erected platform by means of which the invisible make a display of themselves. The so-called war on terror, I mean, and the time, the shape, and the lives it is taking in Iraq. My position becomes sufficiently clear in those words, as tenuous as it sometimes seems to myself. Experiencing the uncertainty, the turmoil and sorrow that was New York City during the days following the destruction of the World Trade Center, I was anxious to see prevented what then felt like an out and out war against the democratic West; but as a descendant of Nazi sympathizers who is convinced that putting an end to thralldom is a noble cause and conflicted about the use of military force to achieve this end, I could only work myself up to a restrained fervor, which soon gave way to bewilderment, anger, and frustration.

It is the fuel that keeps the search engines humming. It is fodder for loudmouthed if often unintelligible webjournalists thriving on the divisive. It is the foundation of many a rashly erected platform by means of which the invisible make a display of themselves. The so-called war on terror, I mean, and the time, the shape, and the lives it is taking in Iraq. My position becomes sufficiently clear in those words, as tenuous as it sometimes seems to myself. Experiencing the uncertainty, the turmoil and sorrow that was New York City during the days following the destruction of the World Trade Center, I was anxious to see prevented what then felt like an out and out war against the democratic West; but as a descendant of Nazi sympathizers who is convinced that putting an end to thralldom is a noble cause and conflicted about the use of military force to achieve this end, I could only work myself up to a restrained fervor, which soon gave way to bewilderment, anger, and frustration. Well, I am off this instant on a short and none-too-well planned trip to the south of England, to which quick exit you owe the uncommon brevity and, what is more irregular still, the antemeridian dispatch of this entry in the broadcastellan journal. However inconvenient this last-minute post might be for my traveling companions, I simply could not wait another year to share this anniversary. True, I excite easily when it comes to the old wireless; but in this case the enthusiasm is not altogether unwarranted.

Well, I am off this instant on a short and none-too-well planned trip to the south of England, to which quick exit you owe the uncommon brevity and, what is more irregular still, the antemeridian dispatch of this entry in the broadcastellan journal. However inconvenient this last-minute post might be for my traveling companions, I simply could not wait another year to share this anniversary. True, I excite easily when it comes to the old wireless; but in this case the enthusiasm is not altogether unwarranted.

I don’t quite understand the concept; nor do I approve of such an abuse of the medium. The radio alarm clock, I mean. It accosts me with tunes and blather when I am least able or inclined to listen appreciatively. I much prefer being turned on by the radio rather than being roused by it to the point of turning it off or wishing it dead and getting on with the conscious side of life. This morning, however, BBC Radio 2—our daybreaker of choice—managed both to surprise and delight me with the following less-than-timely newsitem. Twenty years after her death, British-born Hollywood actress Madeleine Carroll (

I don’t quite understand the concept; nor do I approve of such an abuse of the medium. The radio alarm clock, I mean. It accosts me with tunes and blather when I am least able or inclined to listen appreciatively. I much prefer being turned on by the radio rather than being roused by it to the point of turning it off or wishing it dead and getting on with the conscious side of life. This morning, however, BBC Radio 2—our daybreaker of choice—managed both to surprise and delight me with the following less-than-timely newsitem. Twenty years after her death, British-born Hollywood actress Madeleine Carroll (