The other day I called detective Ellery Queen to the rescue when I found myself in need of some pop-cultural assistance while dealing with a certain case of bigotry in the blogosphere. Searching for a visual aid to prop up my improbable prose, I dug up my copy of Ellery Queen’s Rogues’ Gallery, a 1945 anthology of crime fiction containing radio scripts by Dannay/Lee and John Dickson Carr.

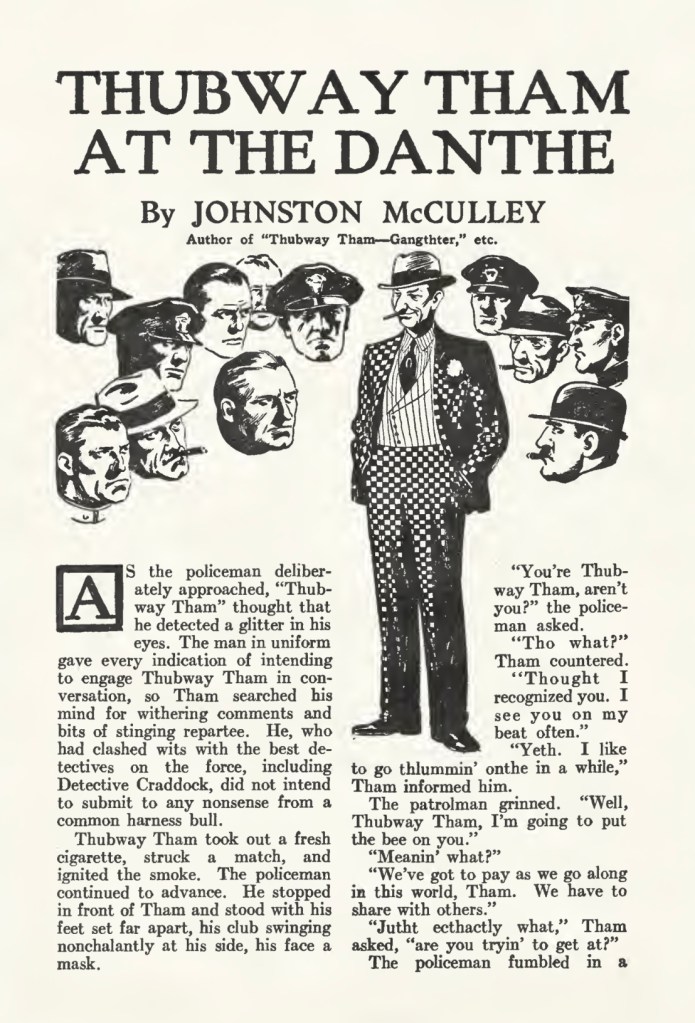

It occurred to me that, aside from those two scripts, I hadn’t read any of the other pieces in said volume. So, leafing through, I happened upon a story about a small-time crook with a big-time speech impediment, a lisp so thick that it earned him the nickname “Thubway Tham.”

Now, Tham never hit it big in radio or the talkies (with that voice, he had about as much of a chance to make it there as silent-screen siren Dolores Costello). That said, he was a rather popular pulp hero in his day, which is reason enough for me to make his acquaintance.

Thubway Tham was the brainchild of Johnston McCulley, creator of the recently if not altogether successfully resuscitated Zorro. According to McCulley (as retold by Mssrs. Ellery Queen), Tham first sprang into action during his author’s visit to New York City in 1919. Observing the crowds being “spewed out of the subway,” McCulley realized that those Big Apple commuters were a veritable herd of cash cows for a clever pickpocket.

In need of a saleable story, McCulley came up with “Subway Sam”; but, somewhat intoxicated at the time, the writer found that his mouth would not cooperate in pronouncing the name and settled for “Thubway Tham” instead.

An artful little dodger who forever thumbed his nose at the luckless Detective Craddock, his arch-enemy, Tham kept appearing and disappearing in story after story (some 182 by 1945, according to his prolific father); yet the times were changing, and what might have been amusing in the prosperous 1920s or reassuring in the lean 1930s was no longer appropriate during the war years, when paper was too precious for the spreading of questionable romances of self-serving criminals and the glorification of devious individualism.

Even less-than upright characters, such as the Saint, were being recruited for the war effort. And unless Tham was satisfied to go underground for the duration, disappearing from public view along with other misfits like honorable, but propagandistically irredeemable Mr. Moto, he was expected to take his hand out of other people’s pockets long enough to lend it to Uncle Sam.

Here is how McCulley’s aging lawbreaker, anno 1944, saw his dilemma:

Thubway Tham found his favorite bench unoccupied, and sat upon it. He was thinking of the war. Many of his younger friends had enlisted or been drafted. Familiar faces were missing. Even certain of the gentry habitually under the eyes of the police had accepted honest toil in shipyards and factories turning out munitions and war supplies.

Tham was sad. A few days before he had tried to enlist and get into a uniform. But there were several things wrong with him physically, the army surgeons found. Tham had started the physical examination feeling rather fit, but by the time they got through with him he was wondering which hospital l would be the best when he unexpectedly collapsed on the street.

He was contemplating now seeking work in some defense plant. But, frankly, that did not appeal to him. Tham was a creature of habit, and a part of that habit was to ignore manual labor. Moreover, work in a war plant would keep him away from his beloved subway.

So, McCulley confronted poor Tham with “the lowest of the low,” with con artists whose prey were “hicks from the sticks,” the “real men” about to fight for their country. Tham could continue stealing, but, punishing those more selfish than he and redistributing his loot, morphed into some simulated Saint, a decidedly less daring and debonair Robin Hood of Modern Crimes.

However valuable such sentimental propaganda might have been, the wartime heroics of turnabout Tham, as recorded in “Thubway Tham, Thivilian,” made for a rather dull and disingenuous Oliver! twist.

What might Thubway Tham be doing these days? Is he still trying his shaky hand at subway robbery? Or has he turned to that superhighway in the sky, where latter-day tricksters, unhampered by physical defects, find ample opportunity to keep their fingers busy and their pockets full?

Don’t let me catch you again, Tham. Disguised as a conscientious “thivilian,” you pretty much wore out your welcome.

This is one of those rare, lugubrious days of landscape-swallowing fogginess on which you might as well retreat, brandy in hand, into the confines of your small but reassuringly familiar study. My thought being as opaque as the wintry sky, my mind as obnubilated as the mist-shrouded hills, I have put aside all semi-intellectual or quasi-artistic endeavors for the moment. Instead, I busy myself cataloguing the

This is one of those rare, lugubrious days of landscape-swallowing fogginess on which you might as well retreat, brandy in hand, into the confines of your small but reassuringly familiar study. My thought being as opaque as the wintry sky, my mind as obnubilated as the mist-shrouded hills, I have put aside all semi-intellectual or quasi-artistic endeavors for the moment. Instead, I busy myself cataloguing the

Well, I was just trying to get into Hollywood Horror House (also known as

Well, I was just trying to get into Hollywood Horror House (also known as  Well, I did say “romancing,” didn’t I? It may have sounded more like “pooping on” in the entry I balderdashed off yesterday. The accompanying image, by the way, referred to the new television series Balderdash and Piffle (on BBC2 in the UK), which invites the public to challenge, edit and amend the Oxford English Dictionary. More about that in a few days, perhaps. So, why “romancing”?

Well, I did say “romancing,” didn’t I? It may have sounded more like “pooping on” in the entry I balderdashed off yesterday. The accompanying image, by the way, referred to the new television series Balderdash and Piffle (on BBC2 in the UK), which invites the public to challenge, edit and amend the Oxford English Dictionary. More about that in a few days, perhaps. So, why “romancing”? Well, the past three weeks or so have been rather trying. My New York City souvenir proves to be one of the most adhesive colds I’ve ever had the misfortune to catch. I’ve slipped up on several occasions composing my blog entries—and am indebted to those who pointed it out to me. For weeks now I have not been able to enjoy my daily dose of classic Hollywood. You know there’s something amiss when you, an ardent movie buff, find yourself dozing off while watching some of the finest motion pictures of Hollywood’s golden age. Over the past few weeks I’ve been falling asleep during or failing to follow film classics including (in order of their disappearance before my eyes) the exotic Greta Garbo vehicle Mata Hari; Jacques Tourneur’s Cat People; Garson Kanin’s Bachelor Mother; the Rogers and Hammerstein musical Carousel; and The Milky Way starring my favorite comedian, Harold Lloyd. What will this cold deprive me of next!

Well, the past three weeks or so have been rather trying. My New York City souvenir proves to be one of the most adhesive colds I’ve ever had the misfortune to catch. I’ve slipped up on several occasions composing my blog entries—and am indebted to those who pointed it out to me. For weeks now I have not been able to enjoy my daily dose of classic Hollywood. You know there’s something amiss when you, an ardent movie buff, find yourself dozing off while watching some of the finest motion pictures of Hollywood’s golden age. Over the past few weeks I’ve been falling asleep during or failing to follow film classics including (in order of their disappearance before my eyes) the exotic Greta Garbo vehicle Mata Hari; Jacques Tourneur’s Cat People; Garson Kanin’s Bachelor Mother; the Rogers and Hammerstein musical Carousel; and The Milky Way starring my favorite comedian, Harold Lloyd. What will this cold deprive me of next!

Well, I am still hoping other internet tourists will join me in rediscovering I Love a Mystery beginning this Halloween (

Well, I am still hoping other internet tourists will join me in rediscovering I Love a Mystery beginning this Halloween (