As much as I enjoy Hollywood musicals, I’ve never sat through The Sound of Music. In fact, before I moved to the US, I had never even heard of the film, let alone anything of the true story behind it. Being born and raised in Germany does have its advantages, you might say; but I am not inclined to be flippant about censorship. Fact is, depictions of Nazism in popular culture were carefully filtered in (West) Germany, even decades after the end of the Third Reich. The reminders of past atrocities and the shared culpability for them were apparently deemed too humiliating or distressing to audiences out to enjoy a bit of cinematic escapism. Perhaps, the decision not to exhibit certain films or to edit and dub them so as to render them inoffensive was based on the notion that the horrors hinted at or exploited for their melodramatic value were too severe to serve as mere diversions. In any case, I was not exposed to the Von Trapps. And when I had my first glimpse of them, I did not feel particularly sorry to have missed out on the acquaintance.

As much as I enjoy Hollywood musicals, I’ve never sat through The Sound of Music. In fact, before I moved to the US, I had never even heard of the film, let alone anything of the true story behind it. Being born and raised in Germany does have its advantages, you might say; but I am not inclined to be flippant about censorship. Fact is, depictions of Nazism in popular culture were carefully filtered in (West) Germany, even decades after the end of the Third Reich. The reminders of past atrocities and the shared culpability for them were apparently deemed too humiliating or distressing to audiences out to enjoy a bit of cinematic escapism. Perhaps, the decision not to exhibit certain films or to edit and dub them so as to render them inoffensive was based on the notion that the horrors hinted at or exploited for their melodramatic value were too severe to serve as mere diversions. In any case, I was not exposed to the Von Trapps. And when I had my first glimpse of them, I did not feel particularly sorry to have missed out on the acquaintance.

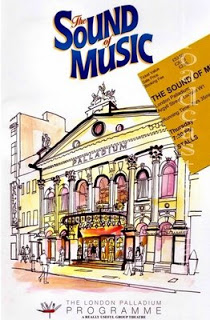

I was as much turned off by the 1960s look of what was meant to have been the late 1930s as I was by those cloying sounds and images. This picture needed to be altogether darker, the music more haunting, more angry and sorrowful than “My Favorite Things.” For years, I avoided what to many remains a sing-a-long occasion. A few weeks ago, the stubborn Teuton in me surrendered at last and got a discount ticket to Andrew Lloyd Webber’s production of the Rodgers and Hammerstein classic at the London Palladium, a production launched and shrewdly promoted back in 2006 by an American Idol-style singing contest in which the British public, along with Sir Andrew, went in search of the perfect Maria.

I can’t say that the West End changed my mind about The Sound of Music. Sure, there are bright and eminently hummable numbers in it, but what is left of the story has less weight than the average supermodel. What is at stake for Maria is not life or liberty, but a chance to trill a few more tunes. No moral dilemma, no sense of danger, no signs of turmoil as Maria grapples with the difficulties of choosing between the convent and the conventional. I don’t expect a treatise on the relationship between fascism and the church; but I sure am tired of those insipid scenes of Sister Activity to which nuns are reduced in popular culture.

In the production’s single instance of dramatically effective set design, the auditorium is transformed into a fascist venue, as brown shirted guards appear in the isles and swastika banners are imposed onto the walls of the Palladium; but the machinery, the show tune factory that is The Sound of Music, does not permit any forebodings to build, any doubt or dread to work on the spectator’s mind. The pageant must go on, dispassionate and smooth as clockwork.

Not everything was quite so well oiled that evening. I knew that what had been mounted here would not amount to anything resembling absorbing melodrama the moment I saw Maria atop a circular platform that was slowly and laboriously tilted in an obvious but feeble imitation of Ted McCord’s Oscar-nominated cinematography. The hills were alive all right; you could hear them aching so loudly that Maria—not the one chosen on the reality program but a paler substitute (the chirpily unengaging Summer Strallen)—couldn’t climb any high note piercing enough to deaden them, spread out as she was on that giant pizza like a slice of parma ham, extra lean.

Less dulcet than the tones produced by those tectonic shifts was whatever emanated from the gaping jaws of the Captain, impersonated that night by Simon MacCorkindale, whose credentials as an actor include, need I say more, featured roles in Falcon Crest and Jaws III. “If you know the notes to sing,” Maria instructs the children in “Do-Re-Mi.” Well, you still can’t “sing most anything” if restricted by the vocal chords of a MacCorkindale, whose rendition of “Edelweiss” should have resulted in his immediate seizure by Nazi officials. The Sound of Music was the croaking Mac’s first—and, let the nuns of the world pray, his last—venture into musical theater.

Less dulcet than the tones produced by those tectonic shifts was whatever emanated from the gaping jaws of the Captain, impersonated that night by Simon MacCorkindale, whose credentials as an actor include, need I say more, featured roles in Falcon Crest and Jaws III. “If you know the notes to sing,” Maria instructs the children in “Do-Re-Mi.” Well, you still can’t “sing most anything” if restricted by the vocal chords of a MacCorkindale, whose rendition of “Edelweiss” should have resulted in his immediate seizure by Nazi officials. The Sound of Music was the croaking Mac’s first—and, let the nuns of the world pray, his last—venture into musical theater.

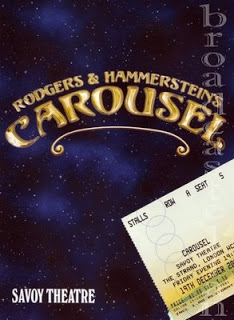

Decidedly more rewarding both tunefully and dramatically is the current West End production of Carousel at the Savoy, which I saw the following day. Starring Jeremiah James as the troubled Billy Bigelow and an earthy, buxom Lesley Garrett as Nettie, it proved a nutritious alternative to pizza with the Von Trapps.

Having spent a week traveling through Wales and the north of England—up a castle, down a gold mine, and over to Port Sunlight, where Lux has its origins—I finally got to sit down again to take in an old-fashioned show. That show was My Fair Lady, a production of which opened last night at the

Having spent a week traveling through Wales and the north of England—up a castle, down a gold mine, and over to Port Sunlight, where Lux has its origins—I finally got to sit down again to take in an old-fashioned show. That show was My Fair Lady, a production of which opened last night at the  According to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, our “universal language” is music. This might account for the international crowd at Budapest’s splendid opera and operetta houses; or perhaps it is ticket prices, which the locals are less likely to tolerate than the visitors in town for a good time. It is like that the world over, I suspect. New Yorkers are hardly the main audience for Broadway shows. What is on offer in any cultural center is largely owing to centrifugal forces. Is it the music that is universally understood? Or is it just that money talks without an accent?

According to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, our “universal language” is music. This might account for the international crowd at Budapest’s splendid opera and operetta houses; or perhaps it is ticket prices, which the locals are less likely to tolerate than the visitors in town for a good time. It is like that the world over, I suspect. New Yorkers are hardly the main audience for Broadway shows. What is on offer in any cultural center is largely owing to centrifugal forces. Is it the music that is universally understood? Or is it just that money talks without an accent?

Well, I’m on his way. Instead of Going Hollywood, where the WGA strike is beginning to make itself felt, I am listening all this week to the BBC, taking in drama, music, and talk. Late to catch up, I started on The Bing Crosby Trail, a six week tour whose first installment took me on a road to California, New York City, and Spokane, where listeners get to meet the daughter, the widow, and many of the contemporaries of the man known as Bing.

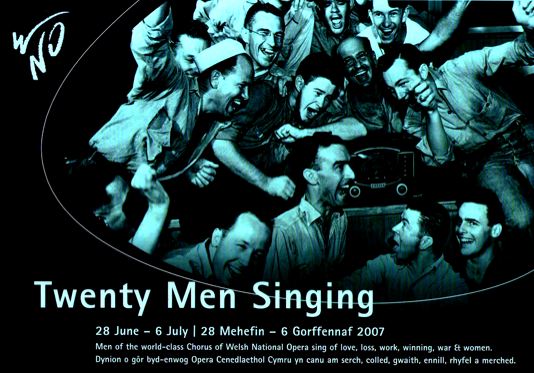

Well, I’m on his way. Instead of Going Hollywood, where the WGA strike is beginning to make itself felt, I am listening all this week to the BBC, taking in drama, music, and talk. Late to catch up, I started on The Bing Crosby Trail, a six week tour whose first installment took me on a road to California, New York City, and Spokane, where listeners get to meet the daughter, the widow, and many of the contemporaries of the man known as Bing. It seems that the proverbial one who’s got more curves than the skeletons on the catwalks has not warbled her last. No, it ain’t over yet. According to my students, at least, whose rallying cries generated enough interest to keep my rather esoterically titled course “Writing for the Ear” alive, death warrants and prematurely issued certificates notwithstanding. The “fat lady,” of course, is the diva who gets to have the last word in opera. I don’t know where the expression originates; but it seems to be true for much of the operatic canon. Tonight, I am going to see Mimi expire in a production of La Bohème, performed by the Mid-Wales Opera Company.

It seems that the proverbial one who’s got more curves than the skeletons on the catwalks has not warbled her last. No, it ain’t over yet. According to my students, at least, whose rallying cries generated enough interest to keep my rather esoterically titled course “Writing for the Ear” alive, death warrants and prematurely issued certificates notwithstanding. The “fat lady,” of course, is the diva who gets to have the last word in opera. I don’t know where the expression originates; but it seems to be true for much of the operatic canon. Tonight, I am going to see Mimi expire in a production of La Bohème, performed by the Mid-Wales Opera Company. Well, I neither know nor care whether it is still considered a gaffe in some circles, but this was the kind of post-Labor Day that makes me want to wear white, or less. Mind you, I was just lounging in our garden, a rare enough treat this year. I am not among those who look toward fall as a fresh and colorful season, marked and marred by decay as it is. In New York City, my former home, September and October come as a relief from the stifling heat, a cooling down for which there is generally no need here in temperate and meteorologically temperamental Wales. Pop culturally speaking, to be sure, autumn is a time of renewal. In the US, at least, there is the fall lineup to look forward to as the end of an arid stretch in which fillers and (starting in the late 1940s) repeats convinced folks of the pleasures to be had outdoors.

Well, I neither know nor care whether it is still considered a gaffe in some circles, but this was the kind of post-Labor Day that makes me want to wear white, or less. Mind you, I was just lounging in our garden, a rare enough treat this year. I am not among those who look toward fall as a fresh and colorful season, marked and marred by decay as it is. In New York City, my former home, September and October come as a relief from the stifling heat, a cooling down for which there is generally no need here in temperate and meteorologically temperamental Wales. Pop culturally speaking, to be sure, autumn is a time of renewal. In the US, at least, there is the fall lineup to look forward to as the end of an arid stretch in which fillers and (starting in the late 1940s) repeats convinced folks of the pleasures to be had outdoors.

Don’t tell me. You’ve had a great time at the beach, enjoyed a picnic with friends and family, followed by a splendid fireworks display on a balmy evening. I mean it, don’t tell me! It’s been raining here for, let’s see, about three weeks, ever since my return from New York City; and today I read a

Don’t tell me. You’ve had a great time at the beach, enjoyed a picnic with friends and family, followed by a splendid fireworks display on a balmy evening. I mean it, don’t tell me! It’s been raining here for, let’s see, about three weeks, ever since my return from New York City; and today I read a