Legend has it that, when asked what Cecil B. DeMille was doing for a living, his five-year-old grand-daughter replied: “He sells soap.” Back then, in 1944, the famous Hollywood director-producer was known to million of Americans as host and nominal producer of the Lux Radio Theater, from the squeaky clean boards of which venue he was heard slipping (or forcefully squeezing) many a none-too-subtle reference to the sponsor’s products into the behind-the-scenes addresses and rehearsed chats with Tinseltown’s luminaries, lines scripted for him by unsung writers selling out in the business of making radio sell.

No doubt, the program generated sizeable business for Lever Brothers; otherwise, the theatrical spin cycle conceived to bang the drum for those Lads of the Lather would not have stayed afloat for two decades, much to the delight of the great (and only proverbially) unwashed. For all its entertainment value, commercial radio was designed to hawk, peddle and tout; and although the spiel heard between the acts of wireless theatricals like Lux has long been superseded by the show and sell of television and the Internet, old radio programs still pay off, no matter how freely they are now shared on the web. In a manner of speaking, they still sell, albeit on a far smaller and downright intimate scale.

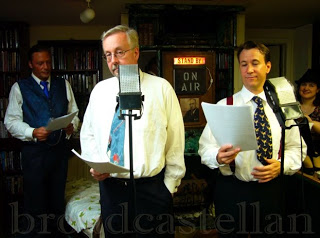

Take W-WOW! Radio. Now in its fourteenth season, the opening of which I attended last month, the W-WOW! Mystery Hour can be spent—heard and seen—on the first Saturday of every month (July and August excepting) from a glorified store room at the back of one of the few remaining independent and specialty booksellers in Manhattan: Partners & Crime down on Greenwich Avenue in the West Village. The commercials recited by the cast are by now the stuff of nostalgia, hilarity, and contention (“In a coast-to-coast test of hundreds of people who smoked only Camels for thirty days, noted throat specialists noted not one single case of throat irritation due to smoking Camels“); but the readings continue to draw prospective customers like myself.

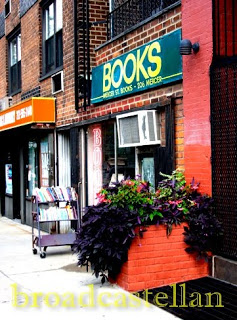

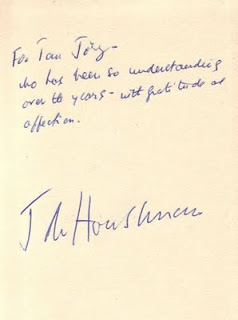

Whenever I am in town, I make a point of making a tour of those stores, even though said tour is getting shorter and more sentimental every year. There are rewards, nonetheless. Two of my latest acquisitions, Susan Ware’s 2005 “radio biography” of the shrewdly if winningly commercial Mary Margaret McBride and John Houseman’s 1972 autobiography Run-through (signed by the author, no less) were sitting on the shelves of Mercer Street Books (pictured) and brought home for about $8 apiece. The latter volume is likely to be of interest to anyone attending the W-WOW! production scheduled for this Saturday, 3 October, when the W-WOW! players are presenting the Mercury Theatre on the Air version of Dracula as adapted by none other than John Houseman.

As Houseman puts it, the Mercury’s “Dracula”—the series’s inaugural broadcast—is “not the corrupt movie version but the original Bram Stoker novel in its full Gothic horror.” Indeed, Houseman’s outstanding adaptation is a challenge worthy of W-WOW!’s voice talent and just the kind of material special effects artist DeLisa White (pictured above, on the right and to the back of those she so ably backs) will sink her teeth into, or whatever sharp and blunt instruments she has at her disposal to make your hair stand on end.

Rather more run-of-the-mill were the scripts chosen for W-WOW!’s September production, which, regrettably, was devoid of vamps. You know, those double-crossing, tough-talking dames that enliven tongue-in-cheek thrillers like The Saint (“Ladies Never Lie . . . Much” or “The Alive Dead Husband,” 7 January 1951) and Richard Diamond (“The Butcher Shop Case,” 7 March 1951 and 9 March 1952), a story penned by Blake “Pink Panther” Edwards and involving a protection racket. The former opened encouragingly, with a wife pretending to have killed a husband who turned out to be yet living, if not for long; but, as it turned out, the dame had less lines than any of the ladies currently in prime time, or any other time for that matter. Sure, crime paid on the air; but sex, or any vague promise of same, sells even better.

That said, I still walked out of Partners & Crime with a book in my hand. As I passed through the store on my way out, an out-of-print copy of A Shot in the Arm caught my eye and refused to let go. Subtitled “Death at the BBC,” John Sherwood’s 1982 mystery novel, set in Broadcasting House anno 1937 and featuring Lord Reith, the dictatorial Baron who ran the place, is just the kind of stuff I am so readily sold on, as I am on browsing in whatever bookstores are still standing offline—if only to give those who are still in the business of vending rare volumes a much-deserved shot in the open and outstretched arm.

Related recordings

“Ladies Never Lie . . . Much,” The Saint (7 January 1951)

“The Butcher Case,” Richard Diamond (7 January 1950)

“The Butcher Case,” Richard Diamond (9 March 1951)

She might have been auditioning for Sunset Blvd. or hoping for some such comeback; then again, she sounded as if acting lay in a distant, silent past. Screen legend Gloria Swanson, I mean, who, on this day, 10 July, in 1947, stepped behind the microphone to make her only appearance on CBS radio’s Suspense series in a thriller titled ”Murder by the Book (a clip of which I appropriated for

She might have been auditioning for Sunset Blvd. or hoping for some such comeback; then again, she sounded as if acting lay in a distant, silent past. Screen legend Gloria Swanson, I mean, who, on this day, 10 July, in 1947, stepped behind the microphone to make her only appearance on CBS radio’s Suspense series in a thriller titled ”Murder by the Book (a clip of which I appropriated for

Being that this is the anniversary of the birth of Guglielmo Marconi, a scientist widely, however mistakenly, regarded as the inventor of the wireless, I am once again lending an ear to the medium with whose plays and personalities this journal was meant to be chiefly concerned. Not that I ever abandoned the subject of audio drama or so-called old-time radio; but efforts to reflect more closely my life and experiences at home or abroad have induced me of late to turn a prominent role into what amounts at times to little more than mere cameos. Besides, “Writing for the Ear” is a course I am offering this fall at the local university; so I had better prick ’em up (my auditory organs, I mean) and come at last to that certain one of my senses.

Being that this is the anniversary of the birth of Guglielmo Marconi, a scientist widely, however mistakenly, regarded as the inventor of the wireless, I am once again lending an ear to the medium with whose plays and personalities this journal was meant to be chiefly concerned. Not that I ever abandoned the subject of audio drama or so-called old-time radio; but efforts to reflect more closely my life and experiences at home or abroad have induced me of late to turn a prominent role into what amounts at times to little more than mere cameos. Besides, “Writing for the Ear” is a course I am offering this fall at the local university; so I had better prick ’em up (my auditory organs, I mean) and come at last to that certain one of my senses.