So it isn’t exactly the 35th of May, the magical anything goes if you dare to imagine kind of day Erich Kästner dreamed up for our delight. Still, it is an extra day, this 29th of February, and ought to be looked upon as extraordinary. Indeed, this rarest 24-hour period in the calendar—the anniversary of Superman’s birth, no less—should really be set aside or simply seized for the carnivalesque. It strikes me as absurd to carry on as usual only to keep our system of charting time from falling apart. Being a man of leisure, confined less by schedules than by the vagaries of the season, I decided to keep out of the rain and find out how this leap year appendage was treated by those in charge of the timing-is-everything, by-the-numbers business-as-usual world of commercial radio, USA.

So it isn’t exactly the 35th of May, the magical anything goes if you dare to imagine kind of day Erich Kästner dreamed up for our delight. Still, it is an extra day, this 29th of February, and ought to be looked upon as extraordinary. Indeed, this rarest 24-hour period in the calendar—the anniversary of Superman’s birth, no less—should really be set aside or simply seized for the carnivalesque. It strikes me as absurd to carry on as usual only to keep our system of charting time from falling apart. Being a man of leisure, confined less by schedules than by the vagaries of the season, I decided to keep out of the rain and find out how this leap year appendage was treated by those in charge of the timing-is-everything, by-the-numbers business-as-usual world of commercial radio, USA.

Rather out of the ordinary, to be sure, was Jack Benny’s 29 February 1948 broadcast. Never one to allow guests a look behind the scenes, Benny had made an exception for his girlfriend, Gladys Zybysko; but those rehearsals, dramatized in flashback, took place on the 28th. I was curious, nonetheless, considering that Sadie Hawkins Day, as it used to be known in the US, is the only day a woman could propose marriage. Would the thoroughly self-sufficient Gladys Zybysko leap at the chance of spending her days with a skinflint like Benny? I didn’t think so. Besides, it never even came to that. Benny was too busy puzzling over a place called “Doo-wah-diddy” (“It ain’t no town and it ain’t no city”), mentioned in “That’s What I Like About the South,” a song to be performed on the broadcast.

On the same night, on another network, The Shadow dealt in his customary fashion with “The Man Who Was Death.” No mention was made of the 29 February. Not that I expect any such reference, considering that those born on this day—like Gilbert and Sullivan’s Frederic in The Pirates of Penzance—remain, numerically speaking, life itself to the very last. So, I kept twisting the dial in search of that twist in our everyday.

Promising “tales of new dimensions in time and space” from “the far horizons of the unknown,” the sci-fi series X Minus One seemed likely to mark the spot. On 29 February 1956 it presented “Hello, Tomorrow,” a fantasy examining a post-apocalyptic society, anno 4195 (alas). However compelling, it is a missed opportunity to match the intercalary with the intergalactic. Say, what calendar do you use in outer space? The problems with such “transcribed” programs is that they were readily recycled and, unlike the live programs broadcast during the 1930s and early-to-mid 1940s, omitted any specific temporal or topical references that would make them appear dated. Besides, “Hello, Tomorrow” would have more aptly been called “Hello Again, Yesterday.” It was a rerun.

Nor was the 29 February 1944 edition of Your Radio Newspaper a bissextile treat. There was none to be had all round; a sobering end to my search for the exceptional. Well, never mind. I, at least, am adhering to tradition by letting my world go temporarily topsy-turvy. To wit, I have permitted my in so many ways better half to propose . . . tonight’s entertainment. “Anything goes” comes at a price: I am subjecting myself to a screening of La vie en rose. It’s French, it’s Piaf—it’s something I can stomach only once every four years. “Extra,” I concluded after this exercise in futility, is not a synonym for “special.”

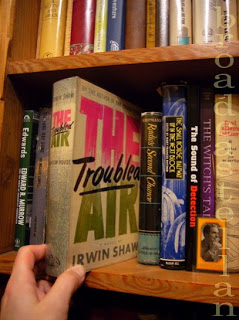

This being the birthday of novelist Irwin Shaw (1913-1984), I dusted off my copy of The Troubled Air (1951) to pay tribute to a radio writer who successfully channelled his anger and frustration by feeding it to the press, a rival medium that was only too pleased to get the dirt on broadcasting. Like his

This being the birthday of novelist Irwin Shaw (1913-1984), I dusted off my copy of The Troubled Air (1951) to pay tribute to a radio writer who successfully channelled his anger and frustration by feeding it to the press, a rival medium that was only too pleased to get the dirt on broadcasting. Like his  As usual, I am slow to catch up. A few years ago, the BBC relinquished the rights to televising the Oscars; and since we are not subscribing to the premium channel that does air them, I am relying on the old wireless to transport me to the events. So, here I am listening to …

As usual, I am slow to catch up. A few years ago, the BBC relinquished the rights to televising the Oscars; and since we are not subscribing to the premium channel that does air them, I am relying on the old wireless to transport me to the events. So, here I am listening to …  As much as I dislike mathematics and however arithmetically challenged I am without a calculator, I very much enjoy compiling lists and studying figures such as box office statistics. I am less interested in watching contemporary film than in finding out how many others have. It gives me an idea of what is popular without having to subject myself to yet another sequel of an indifferently constructed CGI clones. My kind of picture is, on average, at least half a century old. Today, I considered the list of films I have screened of late and rated them, on a scale from one to ten, at the Internet Movie Database. It is not an easy task, this kind of opining by the numbers, as I

As much as I dislike mathematics and however arithmetically challenged I am without a calculator, I very much enjoy compiling lists and studying figures such as box office statistics. I am less interested in watching contemporary film than in finding out how many others have. It gives me an idea of what is popular without having to subject myself to yet another sequel of an indifferently constructed CGI clones. My kind of picture is, on average, at least half a century old. Today, I considered the list of films I have screened of late and rated them, on a scale from one to ten, at the Internet Movie Database. It is not an easy task, this kind of opining by the numbers, as I  Not that I am entirely visual-minded on this my day of reckoning. Once again, I am cataloguing my library of books on broadcasting, a collection that has grown considerably since last I attempted to inventory it. While I am at it, I am scanning some of the covers, so aptly referred to as dust jackets and put them on display where they are more likely to tickle someone’s fancy rather than irritate throat and eye. Pictured are first editions of Francis Chase’s Sound and Fury: An Informal History of Broadcasting (1942), Charles Siepmann’s Radio’s Second Chance (1946), and fred allen’s letters, edited by Joe McCarthy (1965).

Not that I am entirely visual-minded on this my day of reckoning. Once again, I am cataloguing my library of books on broadcasting, a collection that has grown considerably since last I attempted to inventory it. While I am at it, I am scanning some of the covers, so aptly referred to as dust jackets and put them on display where they are more likely to tickle someone’s fancy rather than irritate throat and eye. Pictured are first editions of Francis Chase’s Sound and Fury: An Informal History of Broadcasting (1942), Charles Siepmann’s Radio’s Second Chance (1946), and fred allen’s letters, edited by Joe McCarthy (1965). There is “no glory in radio,” Allen remarked in a letter to Abe Burrows (

There is “no glory in radio,” Allen remarked in a letter to Abe Burrows (

This seems to me just the day to hear about Messrs. Polk and Harding, to listen to the words of Franklin Pierce and Chester Alan Arthur. During the late 1940s and early ‘50s, they were all brought back to life via that great spiritual medium, the wireless. For little less than half an hour at a time, they wafted right into the American home, which, a decade earlier, had been accustomed to so-called Fireside chats from an above determined to come across as being among.

This seems to me just the day to hear about Messrs. Polk and Harding, to listen to the words of Franklin Pierce and Chester Alan Arthur. During the late 1940s and early ‘50s, they were all brought back to life via that great spiritual medium, the wireless. For little less than half an hour at a time, they wafted right into the American home, which, a decade earlier, had been accustomed to so-called Fireside chats from an above determined to come across as being among.