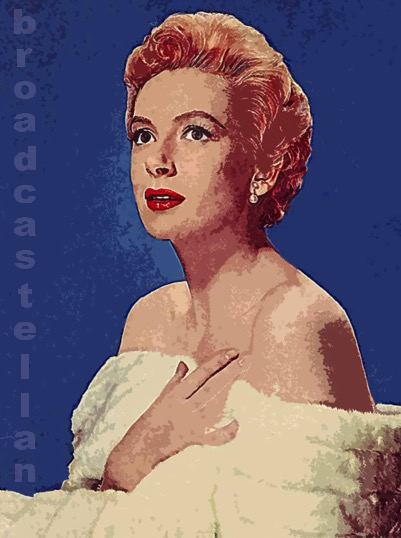

Well, they should have been slipped a Mickey Finn, for starters. Those boys in the back room scribbling gags for Bud Abbott and Lou Costello, I mean. On this day, 15 October, in 1942, the comedy duo was called upon to accommodate Marlene Dietrich, who stepped behind the mike to promote what would turn out to be yet another dud: Pittsburgh. Like Hollywood’s film producers, the writers went no farther than to hark back to Dietrich’s image-revamping comeback Destry Rides Again, released three years earlier. Once again, Dietrich was heard singing a few notes of the raucous barroom number that had pre-war audiences “Falling in Love Again” with the formerly untouchable and largely humorless goddess.

Well, they should have been slipped a Mickey Finn, for starters. Those boys in the back room scribbling gags for Bud Abbott and Lou Costello, I mean. On this day, 15 October, in 1942, the comedy duo was called upon to accommodate Marlene Dietrich, who stepped behind the mike to promote what would turn out to be yet another dud: Pittsburgh. Like Hollywood’s film producers, the writers went no farther than to hark back to Dietrich’s image-revamping comeback Destry Rides Again, released three years earlier. Once again, Dietrich was heard singing a few notes of the raucous barroom number that had pre-war audiences “Falling in Love Again” with the formerly untouchable and largely humorless goddess.

Just a few notes, mind. After which promising introduction, the echo of good old Frenchy faded and gave way for the undistinguished lines of a Wild West sketch involving an alleged bank robbery, Bud and Lou going in search of the culprit, and Dietrich, taken as far from her German roots and world politics as the sound-only, accent accentuating medium would allow, emerging as the prime suspect. “What a fresh kid!” Lou exclaims. “What a stale plot,” the guest star is permitted to sneer.

Even without much of one, Dietrich could still rely on an asset as great as her “expensive pins,” of which bespoke and highly insured commodities the writers went through great length to remind the listener by having her talk of the “pin money” her character (“Marlene,” AKA “Black Pete”) had stashing away in her stockings.

Dietrich could read out the box office receipts that qualified her as poison and still make you swallow and like whatever “leperous distilment” (to class this up with some soundbites from Hamlet) oozed into the “porches” of the ear from that celebrated throat of hers. Hope lay at the bottom of her voice box. She could wrap you around her little finger with her vocal chords alone. Pardon the mixed bag of metaphors; this writer is having an off night, too.

Not that the censors were particularly awake that day. Discovering where Marlene is hiding her savings, self-confessed “baaaad boy” Costello, who earlier told his pal about being in love with a bow-legged cowgirl who had a “terrible time getting her calves together,” is invited to take a peek at the secret spot, exclaiming: “What a place to make a deposit!”

However tacky, getting any word in between those Camel commercials on the Abbott and Costello very nearly translated into money in the bank back in 1942, the year during which the show reportedly averaged higher Hooper ratings than Al Jolson, Eddie Cantor, and Fred Allen.

“The power of radio to help careers has never been better illustrated than in the case of the Rowdy Boys of Stage, Screen, and Airwaves,” contemporary commentators Jack Gaver and Dave Stanley remarked (in There’s Laughter in the Air! [1945]). In 1938, they got their break from vaudeville on Kate Smith’s variety show, which featured them until 1940. They landed a prominent time slot filling in for Fred Allen during his 1940 summer hiatus, by which time they were well on their way to movie stardom. In 1942, they topped the popularity poll conducted by the Motion Picture Herald.

Stars and studios could not afford to ignore the “power of radio,” especially when Manpower was not enough to draw in the crowds. Earlier that year (as reported here), Dietrich had been told to get into radio. Her advisor, comedian Fred Allen, whose team of writers were sly enough to peddle a dumb script as a spoof on the drivel that passed for melodramatic radio entertainment by offering Dietrich the lead in a soap opera titled “Brave Betty Birnbaum.”

“The jokes that Abbott and Costello use are not really too important,” Gaver and Stanley summed up. “Half of the battle is their loudness and a sense of constant turmoil.” Yes, brave they had to be, those leading ladies, when they were sent out into the cornfield of radio comedy. In Dietrich’s case, the 1942 harvest would be none too rich.

It seems that the proverbial one who’s got more curves than the skeletons on the catwalks has not warbled her last. No, it ain’t over yet. According to my students, at least, whose rallying cries generated enough interest to keep my rather esoterically titled course “Writing for the Ear” alive, death warrants and prematurely issued certificates notwithstanding. The “fat lady,” of course, is the diva who gets to have the last word in opera. I don’t know where the expression originates; but it seems to be true for much of the operatic canon. Tonight, I am going to see Mimi expire in a production of La Bohème, performed by the Mid-Wales Opera Company.

It seems that the proverbial one who’s got more curves than the skeletons on the catwalks has not warbled her last. No, it ain’t over yet. According to my students, at least, whose rallying cries generated enough interest to keep my rather esoterically titled course “Writing for the Ear” alive, death warrants and prematurely issued certificates notwithstanding. The “fat lady,” of course, is the diva who gets to have the last word in opera. I don’t know where the expression originates; but it seems to be true for much of the operatic canon. Tonight, I am going to see Mimi expire in a production of La Bohème, performed by the Mid-Wales Opera Company.

I could have gone on. I enjoy going on here about whatever comes to my ears or opens my mind’s eye; and even the realization that too much else is going on to warrant such going-ons generally won’t stop me from sharing it all in this journal. What did stop me (from going on about my recent trip to Prague, I mean) was our phone line, which is just as unpredictable as the Welsh weather—and apparently under it whenever it gets wet. Once again, we have been without phone or internet, owing to wires that seem to have been gnawed at by soggy sheep or are otherwise rotting away where the valley is green with mold.

I could have gone on. I enjoy going on here about whatever comes to my ears or opens my mind’s eye; and even the realization that too much else is going on to warrant such going-ons generally won’t stop me from sharing it all in this journal. What did stop me (from going on about my recent trip to Prague, I mean) was our phone line, which is just as unpredictable as the Welsh weather—and apparently under it whenever it gets wet. Once again, we have been without phone or internet, owing to wires that seem to have been gnawed at by soggy sheep or are otherwise rotting away where the valley is green with mold.

Just where did it go—or go wrong—he wonders, as he passes the could-be-anywhere shopping complex to wend his way back after a Mexican meal and a surprisingly good Long Island Iced Tea to the

Just where did it go—or go wrong—he wonders, as he passes the could-be-anywhere shopping complex to wend his way back after a Mexican meal and a surprisingly good Long Island Iced Tea to the

Well, I don’t always manage it. Keeping my everyday contained in a single journal devoted to popular culture; or working my life around its keeping. Not that I am being secretive about what else is going on. I am merely trying to stay within the boundaries I defined for broadcastellan; and sometimes the connections between old-time radio and my present can only be got at with considerable stretching. I wonder whether Walter Pater had this problem turning his life into a work of art, which no doubt is the most graceful and fulfilling way of controlling ones existence.

Well, I don’t always manage it. Keeping my everyday contained in a single journal devoted to popular culture; or working my life around its keeping. Not that I am being secretive about what else is going on. I am merely trying to stay within the boundaries I defined for broadcastellan; and sometimes the connections between old-time radio and my present can only be got at with considerable stretching. I wonder whether Walter Pater had this problem turning his life into a work of art, which no doubt is the most graceful and fulfilling way of controlling ones existence. There was no getting through it today, neither for the sun, nor for my eyes. A shroud of mist enveloped our cottage, obscuring the views of the hills and valleys beyond the hedge. With nothing in sight—and certainly no end—I just closed my eyes and drifted off again, sleeping the morning (though not the mist) away. On a murky day like this, when you just “want to get away from it all,” the Internet Archive can be relied upon to “offer you … escape,” if you pardon the belabored radio reference. True, with a trip to Prague in the offing, and the sounds and sights of Budapest and New York still readily retrievable from the ever deepening recesses of my mind, I am not exactly desperate for a virtual getaway; nor is it escapism I am after. It is the thrill of discovering and taking in something new that keeps me turning and returning to that amazing resource, filled as the Archive is with rare recordings waiting to be explored.

There was no getting through it today, neither for the sun, nor for my eyes. A shroud of mist enveloped our cottage, obscuring the views of the hills and valleys beyond the hedge. With nothing in sight—and certainly no end—I just closed my eyes and drifted off again, sleeping the morning (though not the mist) away. On a murky day like this, when you just “want to get away from it all,” the Internet Archive can be relied upon to “offer you … escape,” if you pardon the belabored radio reference. True, with a trip to Prague in the offing, and the sounds and sights of Budapest and New York still readily retrievable from the ever deepening recesses of my mind, I am not exactly desperate for a virtual getaway; nor is it escapism I am after. It is the thrill of discovering and taking in something new that keeps me turning and returning to that amazing resource, filled as the Archive is with rare recordings waiting to be explored.