Well, I am feeling strangely liberated. A few days ago, I learned that my BlogMad account had been wiped out as a result of some database corruption—a common occurrence, if comments from fellow web journalists are any indication. I chose not to sign up anew right away, luxuriating instead in the thought of temporarily forgoing those new-fangled ways in favor of an old-fashioned book. Despite my doctorate in literature, I don’t read nearly as much as I ought to these days. So, I took advantage of the first warm day of the season, ripped off my shirt, and grabbed . . . a Trollope. Anthony Trollope, that is, who happens to be one of my favorite authors. Recently, I picked up his Cousin Henry (my, doesn’t this begin to sound so Carry On!) after discovering that this novel is set in Wales, that strange and wild country west of England I am still struggling to call my home.

Well, I am feeling strangely liberated. A few days ago, I learned that my BlogMad account had been wiped out as a result of some database corruption—a common occurrence, if comments from fellow web journalists are any indication. I chose not to sign up anew right away, luxuriating instead in the thought of temporarily forgoing those new-fangled ways in favor of an old-fashioned book. Despite my doctorate in literature, I don’t read nearly as much as I ought to these days. So, I took advantage of the first warm day of the season, ripped off my shirt, and grabbed . . . a Trollope. Anthony Trollope, that is, who happens to be one of my favorite authors. Recently, I picked up his Cousin Henry (my, doesn’t this begin to sound so Carry On!) after discovering that this novel is set in Wales, that strange and wild country west of England I am still struggling to call my home.

Now, Trollope was a decidedly pragmatic novelist. His novels, on the whole, do not concern boys and girls in the throes of love, but—how refreshing!—mature men experiencing various kinds of moral dilemmas or sophisticated quandaries. Elizabeth Bowen wrote a radio play about the author and his characters, but I have yet to come across a production of it. For romance I turn instead to something like Jane Eyre, whose author, Charlotte Brontë, was born on this day, 21 April, in 1816.

What it does not tell you, of course, is that Jane Eyre happens to be one of the most frequently radio-dramatized novels of the Victorian era or, for that matter, of any era. Next to Dickens’s “Christmas Carol,” no other story has aired more often than Jane’s, even though she was often rendered next to unrecognizable in the process.

To those familiar with and fond of the original narrative, the liberties taken by the version-crafters for screen and radio can be rather exasperating. Yet the disdainful sophisticates who dismiss the resulting pop-cultural bastards sight unseen (or sound unheard) sure miss out on some audacious rackets, such as the pitch made by the announcer of the Lux Radio Theatre in the introduction to the 14 June 1948 broadcast of Jane Eyre (or some such gal’s tale)! To accommodate the show’s sponsor, the spokesperson for Lever Brothers was called upon to ponder the question how Ms. Brontë—who, according to one biographer, liked lace—ever managed to wash her clothes without the benefit of Lux Flakes.

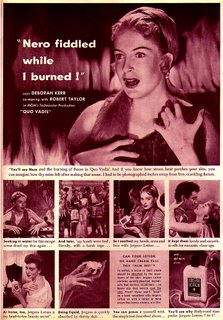

Rather more insightful was a radio lecture delivered on 3 April 1949 during the NBC University Theater production of Jane Eyre, in which Deborah Kerr (pictured above, in another kind of commercial dilemma) portrayed the titular heroine. Noted novelist James Hilton provided a brief but smart commentary, touching upon the reception of the novel, its biographical background, its historical significance, and its relevance for twentieth-century audiences.

To be sure, Hilton conceded, Jane Eyre was a “good story with all the popular ingredients—melodrama, romance, and a happy ending”; but

what gave it life is what gave it birth: a quality of passionate imagination which could make a shy spinster governess the equal, in her own mind and by her own showing, of a Sappho or a Cleopatra.

Come to think of it, Hilton’s mentioning of H. G. Wells’s Ann Veronica in this context recently induced me—someone more readily influenced by smart authors than smarmy advertisers—to get hold of a copy of the latter novel as well.

Many cuts and bruises were inflicted upon plain Jane during those supposedly aureate days of radio; and, with an emphasis on romantic melodrama at the expense of narration, more attention was drawn to that screaming madwoman in the attic than to the reflections of the troubled young governess who discovered her secret. In this respect, old-time radio was like a Victorian orphanage: expect to find negligence, exploitation, and very little recognition, let alone respect, for the suffering brainchild.

Through it all, Jane Eyre survived considerable hardship and cruelty to remain, to this day, one of the most robust heroines of all fiction.

I have often found comfort in the notion that the dead may survive in the minds of those who recall them. It is no mere vanity to desire such afterlives. Indeed, the concept of lingering in each other’s thoughts by virtue of some worthy deed or memorable word can be a significant motivational force in our lives. I am not sure, however, whether the self-images we try to instill in the minds of others as potential extensions of our corporeal existence are to be considered a noble attempt at rescuing our finite lives from triviality or whether these transferable or continuing selves are a construct that trivializes the finality of death. After all, does not the realization that we are perishable render each hour we have left so much more significant?

I have often found comfort in the notion that the dead may survive in the minds of those who recall them. It is no mere vanity to desire such afterlives. Indeed, the concept of lingering in each other’s thoughts by virtue of some worthy deed or memorable word can be a significant motivational force in our lives. I am not sure, however, whether the self-images we try to instill in the minds of others as potential extensions of our corporeal existence are to be considered a noble attempt at rescuing our finite lives from triviality or whether these transferable or continuing selves are a construct that trivializes the finality of death. After all, does not the realization that we are perishable render each hour we have left so much more significant?

I had intended to spend much of today al fresco, our long-neglected garden being in serious need of attention. Dragging the old lawnmower out of hibernal retirement a while ago, I had managed to knock over a can of paint and, the spilled contents being blue, very nearly ended up looking like a Smurf in the process. No sooner had we unleashed the noisy monstrosity, engulfed in a cloud of smoke, than one of its wheels broke off, which immediately put a stop to my horticultural endeavors. It is to the latter mishap on this Not-So-Good Friday and the fact that I am all thumbs (none of which green) that you owe the questionable pleasure of this entry in the broadcastellan journal.

I had intended to spend much of today al fresco, our long-neglected garden being in serious need of attention. Dragging the old lawnmower out of hibernal retirement a while ago, I had managed to knock over a can of paint and, the spilled contents being blue, very nearly ended up looking like a Smurf in the process. No sooner had we unleashed the noisy monstrosity, engulfed in a cloud of smoke, than one of its wheels broke off, which immediately put a stop to my horticultural endeavors. It is to the latter mishap on this Not-So-Good Friday and the fact that I am all thumbs (none of which green) that you owe the questionable pleasure of this entry in the broadcastellan journal. Well, I’ve only been back some forty-eight hours, but the sunny interlude in Cornwall, so poorly captured by my camera, already seems a distant memory. It was Thomas Jefferson—born on this day, 13 April, in 1743—who argued that travelling makes “men wiser, but less happy.” Is this true? “When men of sober age travel,” Jefferson claimed, they may gather useful knowledge, but “are subject ever after to recollections mixed with regret; their affections are weakened by being extended over more objects; and they learn new habits which cannot be gratified when they return home.” Should we limit our exposure to the world by concentrating on what is closest or by selecting a specific if narrow field of inquiry whose soil we continue to till skilfully to reap a rich harvest?

Well, I’ve only been back some forty-eight hours, but the sunny interlude in Cornwall, so poorly captured by my camera, already seems a distant memory. It was Thomas Jefferson—born on this day, 13 April, in 1743—who argued that travelling makes “men wiser, but less happy.” Is this true? “When men of sober age travel,” Jefferson claimed, they may gather useful knowledge, but “are subject ever after to recollections mixed with regret; their affections are weakened by being extended over more objects; and they learn new habits which cannot be gratified when they return home.” Should we limit our exposure to the world by concentrating on what is closest or by selecting a specific if narrow field of inquiry whose soil we continue to till skilfully to reap a rich harvest?

Tomorrow, I am once again crossing the border for a weekend up north in Manchester, England. “Crossing the border” may seem a rather bombastic phrase, considering that I won’t have to show my passport, get fingerprinted or have my luggage inspected at customs. Yet, as I learned after moving from New York City to Wales, the border to England is much more than a mere line on the map, very much guarded by those whose thoughts are kept within that most rigid and impenetrable of confinements—the narrow mind. Urbanites can be most provincial. Thoroughly walled-in, they are often ignorant of a fact stated by Oscar Wilde in An Ideal Husband (1895): “Families are so mixed nowadays. Indeed, as a rule, everybody turns out to be somebody else.”

Tomorrow, I am once again crossing the border for a weekend up north in Manchester, England. “Crossing the border” may seem a rather bombastic phrase, considering that I won’t have to show my passport, get fingerprinted or have my luggage inspected at customs. Yet, as I learned after moving from New York City to Wales, the border to England is much more than a mere line on the map, very much guarded by those whose thoughts are kept within that most rigid and impenetrable of confinements—the narrow mind. Urbanites can be most provincial. Thoroughly walled-in, they are often ignorant of a fact stated by Oscar Wilde in An Ideal Husband (1895): “Families are so mixed nowadays. Indeed, as a rule, everybody turns out to be somebody else.” Well, if my “Do Not View” list over at blogexplosion may be drawn on as ocular proof, the blogosphere is the stomping ground for today’s self-styled propagandists. Operating in the relative anonymity of the internet, webjournalists have seized the new medium as their Hyde Park Corner, a space where they can whine and opine vociferously while hiding behind the latter-day scarves of generic skins and colorful pseudonyms. How effective is such ranting, however relevant or worthwhile the cause? Is debate, so rarely encouraged by loudmouthed badmouthing, still possible among the media-blitzing nobodies of feuding weblocs and those permitting themselves to be caught in between? That I don’t have any ready answers only makes such questions all the more worth raising.

Well, if my “Do Not View” list over at blogexplosion may be drawn on as ocular proof, the blogosphere is the stomping ground for today’s self-styled propagandists. Operating in the relative anonymity of the internet, webjournalists have seized the new medium as their Hyde Park Corner, a space where they can whine and opine vociferously while hiding behind the latter-day scarves of generic skins and colorful pseudonyms. How effective is such ranting, however relevant or worthwhile the cause? Is debate, so rarely encouraged by loudmouthed badmouthing, still possible among the media-blitzing nobodies of feuding weblocs and those permitting themselves to be caught in between? That I don’t have any ready answers only makes such questions all the more worth raising.