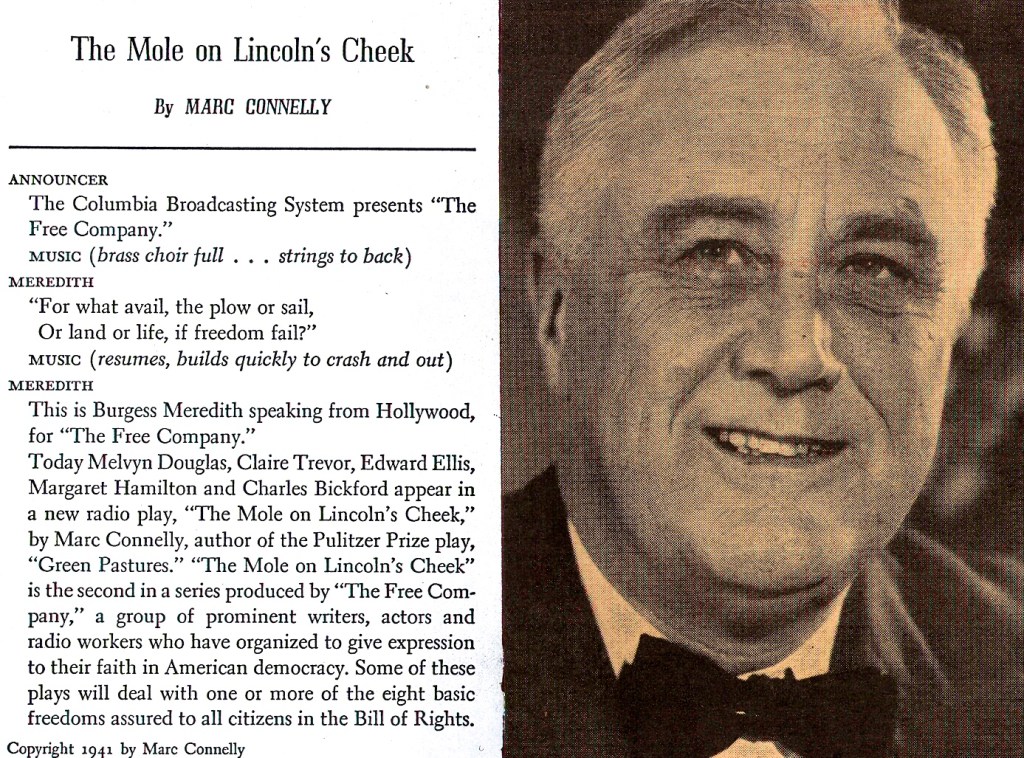

Some thirty years after making her debut in silent movies, Lillian Gish became all voice when, on 9 September 1943, she appeared before the mind’s eye of listeners to CBS’s thriller anthology Suspense. Gish’s performance in the play “Marry for Murder” was announced as one of the “rare radio appearances” by a star who “occupied a unique place in the affections of moviegoers ever since the screen first became of age.” Together with her sister Dorothy (left, in a picture taken from Billips and Pierce’s informative Lux Presents Hollywood), Gish had twice performed on the then new and ambitious Lux Radio Theatre, assuming the part of Jo in “Little Women” (21 April 1935) and recreating one of her most famous silent screen roles in “Way Down East” (25 November 1935)—but that had been years ago in the early days of network drama.

In the late 1930s, she had twice been a panelist on the celebrity quiz program Information, Please and was later to act in a number of dramatic anthologies and variety programs, including Arthur Hopkins Presents and the Theater Guild on the Air. In a medium that demanded and devoured talent daily, her isolated guest spots had been few and far between. Even more rare had been her roles in film after the demise of her mute métier (Top Man, her fourth sound film, was to open in the US a few days after the “Marry for Murder” broadcast); so, the sounding of a silent screen belle must have remained somewhat of a novelty act to many American listeners. Unfortunately, the evening’s entertainment had little of the grace and passion of Miss Gish’s celebrated on-screen histrionics.

Heard again tonight on the WRVO Playhouse, “Marry for Murder” is a routine affair, an is-she-or-ain’t-she thriller that requires little guess work from the audience and yields even fewer surprises. It is a story told too often—and often better, too—on Suspense. Still, the tone of Ray Collins’s narrative and the ominous sounds of the fog horn add some slight intrigue to the Way Down East yarn of recent widow and newlywed Letty Hawthorne, “a frightened, neurotic creature who seemed destined to be a perfect victim” for her domineering husband. Living rather close to “Philomel Cottage” or taking more than a page out of “The Diary of Sophronia Winters,” aren’t they?

The story is told from the perspective of Letty’s friend Phil (Collins), an attorney who was called upon to assist in drawing up a new will for Letty’s husband Mark. When Letty expresses herself anxious to compose a will as well, Phil—a lover of whodunits—speculates whether Mark might not have urged his wife to do so in order to do her in and get her dough. Heard through a filter, Letty’s words “but if I’m found dead” repeat in Phil’s ear until he is convinced of Mark’s villainous intentions. That is, until . . .

Since the three-character play opens with the announcement that Letty is dead, the directions the plot could take are rather limited (unless we are to distrust Phil’s narrative altogether). Radio thrillers often suffer from simplifications, restrictions demanded not only by the lack of time allotted to each play in a medium catering to commerce but by the difficulties aural drama poses for an audience that struggles to take in complex information when playing a puzzle by ear.

“Marry for Murder” might still have been an intriguing character study, like those starring the formidable Agnes Moorehead. Ms. Gish, alas, overdoes the contrast between mousy and monstrous, and her line readings are not always assured. Her Letty here bears little resemblance to her haunted namesake in The Wind (1928), her final silent. Now, I won’t stoop to saying that the actress was a Gish out of water—but she was not quite in her element here. Let’s see whether I can manage to dig up a more satisfying anniversary tomorrow . . .