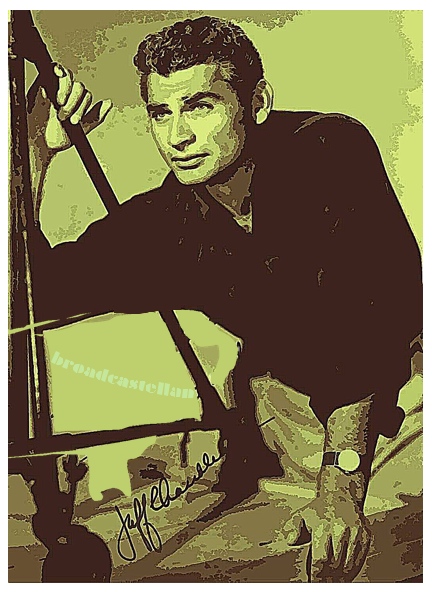

Well, the first thing I thought of when I heard about the passing of screen actress Laraine Day on 10 November 2007 was this remark by Alfred Hitchcock, who directed her in Foreign Correspondent (1940): “I would have liked to have a bigger star.” He could not have been faced with a brighter one. Best known in the 1940s for her recurring role of nurse Mary Lamont in a series of Dr. Kildare movies, Day (seen left in a picture taken from my copy of the 3-9 January 1942 issue of Movie-Radio Guide) was as bright as her name suggested. There seemed to be no edge from which to push to her into more ambitious performances. She was just so darn nice . . . at least until she was forced to give back that pretty Locket.

In The Locket (1946), Day’s cheerful personality is being cleverly exploited to make audiences wonder whether her character, Nancy, is really as charming and uncomplicated as she seems. “She is nice,” a woman attending Nancy’s wedding observes. “She’s lucky,” another guest replies. “If you’re nice, you have to be lucky,” the first one counters, only to be dealt with the riposte that “[i]f you’re lucky, you can afford to be nice.”

Nancy can afford to be nice, however little happiness being a good girl managed to get her as a child; but is she just Mrs. Lucky to have landed such a well-to-do husband, or has her not being quite so nice something to do with it? The Locket, in which Day stars opposite Robert Mitchum, Brian Aherne, and Gene Raymond, is Hitchcock’s Marnie without the sex angle. It is a dark, labyrinthine thriller that casts welcome shadows on the brightness of Ms. Day.

Before making her frequent US television appearances, hosting her own program, Daydreaming with Laraine (1951), and starring in a number of Lux Video Theater productions, Day was heard on the Lux Radio Theater in recreations of her screen roles in Mr. Lucky (1943) and Bride by Mistake (1944). She was also cast in a number of original radio plays produced by the Cavalcade of America (such as in “The Camels Are Coming,” opposite her Foreign Correspondent co-star Joel McCrea).

On Biography in Sound, Day let listeners in on the home life of her husband, Brooklyn Dodgers manager Leo Durocher, with whom she also appeared on Tallulah Bankhead’s Big Show (4 February 1951), in which Day’s clean image was contrasted with that of her irascible husband:

Bankhead: Well, I must say, Laraine, that being the wife of a stormy baseball manager doesn’t seem to have changed you very much. You still have that fresh, lovely, scrubbed look.

Day: Why shouldn’t I look scrubbed? Every time we have an argument, Leo sends me to the showers.

Considering that Day’s projected identity resembles an ad for toilet soap, it is not surprising that she made several return visits to the Lux Radio Theater. Introduced as “ever lovely” by Mr. DeMille, Day enjoyed a rather more interesting vehicle than her own comedies in the mystery “The Unguarded Hour” (4 December 1944).

In that adaptation for radio (of a movie based on a stage drama that itself was an adaptation), Day plays a valiant wife who tries to protect her husband from a scandal of which he is unaware. His words, uttered by co-star Robert Montgomery, capture what is the Laraine Day persona:

How do you think I came to worship you? Because you’re so pretty? Because you win large silver cups jumping horses or play good bridge? No, darling. You have what’s called quality. It’s kindness, it’s generosity, that makes all the rest of us feel just a little shoddy.

Well, it wasn’t exactly the Summer of Love, back in 1968, when American film and television actor Robert Vaughn, then known to millions of Americans as “Napoleon Solo” came to Czechoslovakia to play a Nazi officer in The Bridge at Remagen. Four decades later, Vaughn got the opportunity to share his experience in Tracy Spottiswoode’s radio play “Solo Behind the Curtain.” The play aired last Monday on BBC Radio 4.

Well, it wasn’t exactly the Summer of Love, back in 1968, when American film and television actor Robert Vaughn, then known to millions of Americans as “Napoleon Solo” came to Czechoslovakia to play a Nazi officer in The Bridge at Remagen. Four decades later, Vaughn got the opportunity to share his experience in Tracy Spottiswoode’s radio play “Solo Behind the Curtain.” The play aired last Monday on BBC Radio 4.

How odd, I thought, when I heard myself saying that, instead of screening our customary late night movie, I would retire early because . . . I had a film to catch. The Fflics festival (

How odd, I thought, when I heard myself saying that, instead of screening our customary late night movie, I would retire early because . . . I had a film to catch. The Fflics festival (