|

Well, I’ve never been to Hollywood, tempting offers involving a cat, Elizabeth Taylor’s granddaughter, and a place to stay in LA notwithstanding. You don’t need to be going way out west, though, to be in the presence of Tinseltown’s past, to sense the influence of its players and witness their follies. Now, I am not referring to the likes of Ms. Catherine Zeta-Jones, who was born here in Wales. I mean stars, not celebrities. To be sure, I am somewhat of an Occidental Tourist. Where others, traveling in the Welsh countryside, will find traces of ancient history or sights that quicken the pulse of the most seasoned horticulturalist, I see signs of old Hollywoodland. Take the castle of St. Donats, for instance.

These days, St. Donats is a sort of Hogwarts for assorted Muggles, which is to say that it is an exclusive college for international students, many of whom, if my ears did not deceive me as we walked across the campus last week, come here from the United States. The castle has a centuries-spanning past, as is customary in the case of such fortifications; but in my case, the history lesson exhausted itself in reflections about its state anno 1925, when it got into the ink and blood-stained hands of media tycoon William Randolph Hearst and the far daintier ones of his lovely companion, screen actress Marion Davies (shown in an autographed picture of unverified authenticity from my collection).

Though better known as a silent screen actress, Davies transitioned successfully to sound film and was no stranger to radio. On the air, she starred in the Lux Radio Theater productions of “The Brat” (13 July 1936) and “Peg ‘o My Heart” (29 Nov. 1937), in which she recreated of one of her sentimental talkie roles. Despite her stardom in the 1920s and ‘30s, Davies has long suffered ridicule and neglect, an unwarranted disrepute largely owing to Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. A caricature of Hearst, it leaves audiences with the impression that Davies was the delusional mistress of an influential mogul who humored her whims by purchasing her fame and foisting her lack of talent on an unimpressed multitude. Anyone who has seen Davies in films like The Patsy or Show People knows this to be slanderous. The Brooklynite with the Welsh surname was a brilliant comedienne, far more accomplished than neo-Hollywood A-lister Kirsten Dunst, who impersonated her in the speculative yet tedious Cat’s Meow (2001).

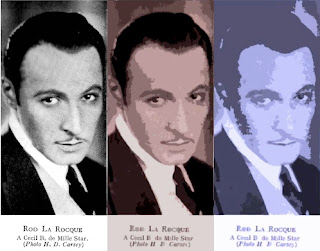

A 1927 volume titled Alice in Movieland (previously raided for a picture of silent screen star Rod La Rocque), attests to Davies’s fondness for Britain: “Well, yes, I d-do admire the Prince of Wales,” she confessed, “and I d-did try to look like him when I played the boy in the lovely uniform in my picture Graustark.” The picture was the delightful yet rarely screened Beverly of Graustark, which, along with a dozen other Davies features, I had the good fortune of catching at New York’s Film Forum some years back. “I love to do boys parts,” Davies added; and as Beverly (listed high among the films I got around to rating on the Internet Movie Database) she is at her most charmingly androgynous.

Unlike her relationship with Hearst, the star’s Hollywood bungalow was no modern affair. It featured a “pure” Tudor door leading to a Tudor hall. “Nothing Pullman about this!” the author of Alice in Movieland marveled. Yet it wasn’t “nearly Tudor enough,” Davies told her. She was determined to move house “some day”—or have her house moved: “It’s got to be the most Tudor thing in the world. I shall have it t-taken away somewhere else, and another one, m-much more beautiful b-built in its place [. . .].”

“[S]ome day,” she knew, was not too far off. Apparently, the Xanadoozy of an imported castle that is San Simeon was not enough for Hearst; perhaps, it was rather too much, too grand and imposing, even for him. Hearst was getting on in years and wanted a quiet retreat for himself and Ms. Davies. A 14th-century castle overlooking the strait known as the Bristol Channel was his idea of quaint, I gather. According to Davies biographer Lawrence Guiles, getting it ready involved the installation of an additional forty-seven bathrooms. And I find the idea of renovating our newly purchased three-bathroom, semi-detached Edwardian house in town daunting!

Unlike San Simeon, which I visited on an August so foggy it suggested Autumn in Wales rather than sunny California, St. Donats is open to the public only for a few days each year, after its current residents are flown out and the school shuts down in mid-Summer. I am determined to go back for another look. To me, it’ll be like Going Hollywood.

The show must go on, as they say. They, obviously, have not been on British soil this summer,

The show must go on, as they say. They, obviously, have not been on British soil this summer,  Well, I suppose we have all taken trips that have changed our lives. After all, why else go anywhere! If it had not been for a New York City subway ride and a brisk walk to Rockefeller Center on an afternoon in December, I would never have ended up here in Wales (a virtual tour of which is being attempted in

Well, I suppose we have all taken trips that have changed our lives. After all, why else go anywhere! If it had not been for a New York City subway ride and a brisk walk to Rockefeller Center on an afternoon in December, I would never have ended up here in Wales (a virtual tour of which is being attempted in

She might have been auditioning for Sunset Blvd. or hoping for some such comeback; then again, she sounded as if acting lay in a distant, silent past. Screen legend Gloria Swanson, I mean, who, on this day, 10 July, in 1947, stepped behind the microphone to make her only appearance on CBS radio’s Suspense series in a thriller titled ”Murder by the Book (a clip of which I appropriated for

She might have been auditioning for Sunset Blvd. or hoping for some such comeback; then again, she sounded as if acting lay in a distant, silent past. Screen legend Gloria Swanson, I mean, who, on this day, 10 July, in 1947, stepped behind the microphone to make her only appearance on CBS radio’s Suspense series in a thriller titled ”Murder by the Book (a clip of which I appropriated for  I have been frequently miscast in the story of my life. And matters weren’t always helped by my being in charge of the casting. I was never more out of my element, which is neither quite earth nor air, as during those twenty months of civil service that I spent vaguely resembling a nurse’s aide. The stethoscope dangling around my neck may have fooled some of the patients some of the time; but my half-hearted attempts at hospital corners soon ruined whatever impression such a prop could have made upon them. Not that Hollywood fares any better in its imitations of strife, even though more harm comes to the reputation of the nursing profession than to the sick and injured by giving the so-called White Angel a tint of the Blue. Unless cast in minor roles, Hollywood nurses are as glamorous and rhinestonian as showgirls.

I have been frequently miscast in the story of my life. And matters weren’t always helped by my being in charge of the casting. I was never more out of my element, which is neither quite earth nor air, as during those twenty months of civil service that I spent vaguely resembling a nurse’s aide. The stethoscope dangling around my neck may have fooled some of the patients some of the time; but my half-hearted attempts at hospital corners soon ruined whatever impression such a prop could have made upon them. Not that Hollywood fares any better in its imitations of strife, even though more harm comes to the reputation of the nursing profession than to the sick and injured by giving the so-called White Angel a tint of the Blue. Unless cast in minor roles, Hollywood nurses are as glamorous and rhinestonian as showgirls. When I read that Lamont Cranston is being resurrected for another big screen adventure scheduled to begin in 2010, I decided to catch up with one of the earlier Shadow plays. The Shadow, of course, always played well on the radio. On this day, 26 June, in 1938, he was again called into action when a “Blind Beggar Dies” after refusing to share his pittance with a gang of racketeers. The blind beggars alive to such melodrama and asking for more were millions of American radio listeners tuning in to follow the exploits of that “wealthy man about town” who was able to “cloud men’s minds” while opening them to the wonders of non-visual storytelling.

When I read that Lamont Cranston is being resurrected for another big screen adventure scheduled to begin in 2010, I decided to catch up with one of the earlier Shadow plays. The Shadow, of course, always played well on the radio. On this day, 26 June, in 1938, he was again called into action when a “Blind Beggar Dies” after refusing to share his pittance with a gang of racketeers. The blind beggars alive to such melodrama and asking for more were millions of American radio listeners tuning in to follow the exploits of that “wealthy man about town” who was able to “cloud men’s minds” while opening them to the wonders of non-visual storytelling.