Sure, his life near Concord, Massachusetts, as he describes it in Walden, was a quiet one. Thoreau “kept neither dog, cat, cow, pig, nor hens, so that you would have said there was a deficiency of domestic sounds; neither the chum, nor the spinning-wheel, nor even the singing of the kettle, nor the hissing of the urn, nor children crying, to comfort one. An old-fashioned man would have lost his senses or died of ennui before this.”

There is violence in the phrase. And for once I can sense it. Silence being “broken,” I mean. For the next two months or so, my life will be less quiet than I have come to live and like it of late. There will be old friends visiting in July and September, there will be travels in good company, and there will be reunions in New York and in New England this August. I shall endeavor to keep my journal all the while; but journals like this are so much easier to keep in the monotone and silence of a retiring life, a life which need not be tired or tiresome as long as there are thoughts to be spun from whatever impulses and impressions there are to be got and gathered in the everyday. Such contemplative quiet, which to some might spell disquietude, was experienced by Henry David Thoreau, who was born on this day, 12 July, in 1817.

There is violence in the phrase. And for once I can sense it. Silence being “broken,” I mean. For the next two months or so, my life will be less quiet than I have come to live and like it of late. There will be old friends visiting in July and September, there will be travels in good company, and there will be reunions in New York and in New England this August. I shall endeavor to keep my journal all the while; but journals like this are so much easier to keep in the monotone and silence of a retiring life, a life which need not be tired or tiresome as long as there are thoughts to be spun from whatever impulses and impressions there are to be got and gathered in the everyday. Such contemplative quiet, which to some might spell disquietude, was experienced by Henry David Thoreau, who was born on this day, 12 July, in 1817.

Yet even in its remoteness, his life was still filled with the “Sounds” to which Thoreau dedicated a chapter of Walden. In it, he argues that, while “confined to books,” we are “in danger of forgetting the language which all things and events speak without metaphor, which alone is copious and standard. Much is published, but little printed.” What he found being made public were the sounds that not only surrounded but defined his everyday. During that first summer at Walden, Thoreau did not read. Instead, he looked, listened, and took in:

I had this advantage, at least, in my mode of life, over those who were obliged to look abroad for amusement, to society and the theatre, that my life itself was become my amusement and never ceased to be novel. It was a drama of many scenes and without an end.

Even then, the drama of the scheduled, orderly life of the city was penetrating the quiet woods, sounds that told of a life governed by the ticking of clocks rather than the time told by the elements and the stirrings of nature:

The whistle of the locomotive penetrates my woods summer and winter, sounding like the scream of a hawk sailing over some farmer’s yard, informing me that many restless city merchants are arriving within the circle of the town, or adventurous country traders from the other side. As they come under one horizon, they shout their warning to get off the track to the other, heard sometimes through the circles of two towns. Here come your groceries, country; your rations, countrymen! Nor is there any man so independent on his farm that he can say them nay. And here’s your pay for them! screams the countryman’s whistle; timber like long battering-rams going twenty miles an hour against the city’s walls, and chairs enough to seat all the weary and heavy-laden that dwell within them. With such huge and lumbering civility the country hands a chair to the city. All the Indian huckleberry hills are stripped, all the cranberry meadows are raked into the city. Up comes the cotton, down goes the woven cloth; up comes the silk, down goes the woollen; up come the books, but down goes the wit that writes them.

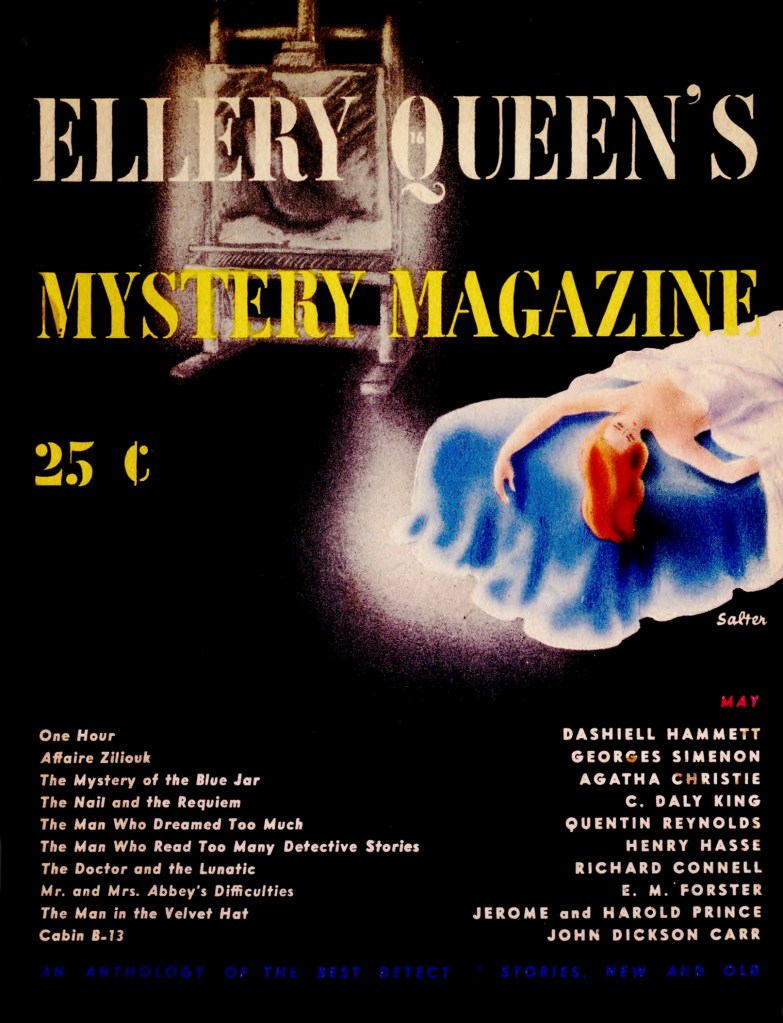

The wits writing plays for old-time radio, who often lent Walt Whitman their ear, very rarely listened to Thoreau, even though a sound effects artist might have appreciated the noise that lent rhythm to Thoreau’s seemingly disorderly existence. Perhaps, his civil disobedience went against the grain of those laboring in a mass medium whose commercial sponsors counted on conformity.

An impersonation of Thoreau was heard, however briefly, in “The Heart and the Fountain,” a radio play about his contemporary, Margaret Fuller. Produced by the Cavalcade of America it was presented on 28 April 1941—at a time when it suited American broadcasters to be quiet about the war in Europe, a time when life on a commune like Brook Farm sounded like escapism,” a Blithedale Romance to blot out thoughts of Blighty.

Getting away from modernity need not be an escape; it can be a chance to come to your senses by subjecting yourself to silence and simplicity—a challenge that, in an age of over-stimulation, may very well drive us out of our narrow minds.

My students never knew it, but I can be a right pushover when it comes to sentiment. I weep, publicly and almost unabashedly, at the sight of a Landseer painting like “His Only Friend.” I enjoy being manipulated that way and am pleased to find my senses receptive to the melodramatic, the dubious arts some denounce as kitsch and others approach only as camp. Nor do I mind being aware of being taken in—unless the trick doesn’t quite come off and I am left disappointed, unmoved, or get downright cross. Disappointed because I was promised a chance to exercise my passions in the relative safety of the controlled environment that is an aesthetic experience. Cold because the passions could not be provoked, despite appreciable effort; and hostile because my intellect rebukes me for having been put on hold for something clearly not worth the shutting down of reason.

My students never knew it, but I can be a right pushover when it comes to sentiment. I weep, publicly and almost unabashedly, at the sight of a Landseer painting like “His Only Friend.” I enjoy being manipulated that way and am pleased to find my senses receptive to the melodramatic, the dubious arts some denounce as kitsch and others approach only as camp. Nor do I mind being aware of being taken in—unless the trick doesn’t quite come off and I am left disappointed, unmoved, or get downright cross. Disappointed because I was promised a chance to exercise my passions in the relative safety of the controlled environment that is an aesthetic experience. Cold because the passions could not be provoked, despite appreciable effort; and hostile because my intellect rebukes me for having been put on hold for something clearly not worth the shutting down of reason. Well, sir, it’s a few minutes or so past six o’clock in the evening as our scene opens now, and here in the garden of the small house halfway up in the Welsh hills we discover Dr. Harry Heuser setting the table for a barbecue dinner. Sorting the flatware, he still keeps an eye on Montague, his Jack Russell terrier. Meanwhile, the side dishes are being prepared in the kitchen and the telephone is ringing. Listen.

Well, sir, it’s a few minutes or so past six o’clock in the evening as our scene opens now, and here in the garden of the small house halfway up in the Welsh hills we discover Dr. Harry Heuser setting the table for a barbecue dinner. Sorting the flatware, he still keeps an eye on Montague, his Jack Russell terrier. Meanwhile, the side dishes are being prepared in the kitchen and the telephone is ringing. Listen. Well, I’ll probably laugh about it—eventually. Not a day in my life passes without mishaps, some major, some trivial, all vexing. Sure, I could blame it now on Montague, our new canine companion. After all, dogs are expected to be inept, to be indifferent to our technological comforts and headaches; but a few remaining bristles on that scouring brush called conscience go against the grain of my indolence and continue to tickle until I make a clean breast of it. The “it,” this time around, is a cordless phone plunged into the watery grave of a bathtub. The rest, as they say (in Hamlet) is silence.

Well, I’ll probably laugh about it—eventually. Not a day in my life passes without mishaps, some major, some trivial, all vexing. Sure, I could blame it now on Montague, our new canine companion. After all, dogs are expected to be inept, to be indifferent to our technological comforts and headaches; but a few remaining bristles on that scouring brush called conscience go against the grain of my indolence and continue to tickle until I make a clean breast of it. The “it,” this time around, is a cordless phone plunged into the watery grave of a bathtub. The rest, as they say (in Hamlet) is silence. Well, how are you feeling today? According to one British study, 23 June is the

Well, how are you feeling today? According to one British study, 23 June is the