I am often too lost in whatever thoughts go through that absent mind of mine to take note of what goes on in the world or who among the world’s notables have departed it of late. Else I am too slow to gather those thoughts in time for anything approaching timely. Enter fellow web journalists Ivan Shreve, on whom you can depend for the latest in great names to have joined the parade of late lamented.

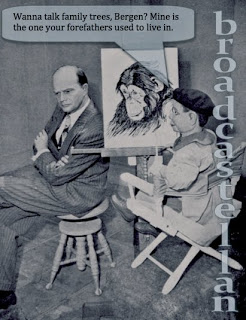

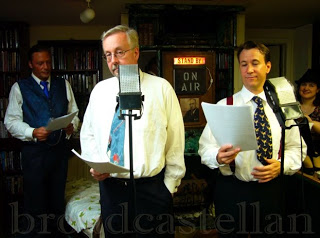

As I learned catching up with The Thrilling Days of Yesteryear this morning, one of the most prolific producers of radio drama in the United States passed away last Friday at the age of ninety-nine: Himan Brown (pictured here, to the left of Raymond Edward Johnson and Claude Rains, during a no doubt brief script conference for Inner Sanctum Mysteries).

Why “no doubt brief”? Well, Brown was not only one of the busiest men in radio, he was also one of the thriftiest—which, his skills and personality aside, is how he got so far so fast in a business that valued performers over producers. According to an article published in the July 1943 issue of Tune In magazine, Brown, then thirty-three, already had some fifteen thousand radio programs to his credit, and, at one time, “had thirty-five of them going each week.”

If he “almost ha[d] a corner on radio horror programs,” it was due largely to his reputation as the medium’s “champion corner cutter,” which is how radio actor Joseph Julian describes the “fabulous Himan Brown” in his memoirs.

For starters, Brown was a “one-man operation.” As Julian points out, the “fabulous” one

produced, cast, and directed of all his shows himself. He never even had an office. He’d make his phone calls from home, or use a phone at one of the studios. He had shrewd understanding of script values and an outsize charm that seduced performers to work for him for less than they would for anyone else.

Brown was involved in all aspects of radio production, and understood them in both dramatic and economic terms. “We must write our scripts with the constant vision of a dollar sign before our eyes,” he told the editors of The Microphone. Interviewed for the magazine’s 14 July 1934 issue, he deplored the industry’s insistence on

employing only the most microphone-experienced actors, who, as Julian points out, “could deliver quickly, thus saving on rehearsal pay and studio costs,” Brown was able to “sell a program at a lower price than his competitors.” Those who assisted him to beat the competition by reading their lines without much instruction appreciated that Brown provided them with steady work, made fewer “demands on their time,” which, in turn, created a “pleasant working atmosphere.”

Julian claims that Brown had made “a million dollars by the time he was twenty-four.” In later life, Brown made a donation in excess of that amount to Brooklyn College, where he taught radio drama. Even on his way up, the enterprising producer opened doors, creaking or otherwise, for young New York writers like Irwin Shaw, who, as Michael Shnayerson recounts in his biography of the noted playwright-novelist, owed his career in radio to Brown, however much Shaw came to resent the experience.

“Still another newspaper cartoon strip comes to the air,” Radio Guide for the week ending 16 February 1935 announced. The program in question was Dick Tracy. “The scripts are to be written by Erwin Shaw [sic] and produced by Himan Brown, who produces The Gumps and Marie, the Little French Princess.”

Clearly, the 1943 article in Tune In, which portrays Brown as a “lone wolf” who was “something of a mystery even within the industry,” is rather overstating it when asserting that the producer had remained “practically unknown to the listening public.” To avid dial twisters—those choosy enough to pick up periodicals like Tune In and its predecessors—the noted producer was already a household name in the mid-1930. How else could readers of the February 1935 issue of Radio Stars be presumed to care that, in November 1934, the “stork left a brand new young man at the home of Mr. and Mrs. Himan Brown”?

It was a rarity, though, for producers to be hailed as “Radio Stars,” among whom those reading the commercial were far more prominent than those preparing the scripts. Perhaps, it was Brown’s past that aided him here, as surely it did in his handling of his numerous programs. As the 1934 article in Microphone reminded me, the producer of series like Little Italy and Jack Dempsey’s Gymnasium was then still referred to as writer, director and “actor [. . .] of his plays.”

Brown himself played Papa Marino in Little Italy, and, if an article in the January 14-20 issue of Radio Guide is to be believed, studied the Italian accent of his Brooklyn neighbors so carefully that he was being mistaken for a paisan.

Given his full schedule and reliable troupe of performers, that ambition (his “greatest,” according to Tune In) remained largely unfulfilled. After all, even a “one-man operation” cannot be expected to be quite this self-sufficient . . .

Related recording

Himan Brown recalling the origins of Inner Sanctum Mysteries in a 1998 interview

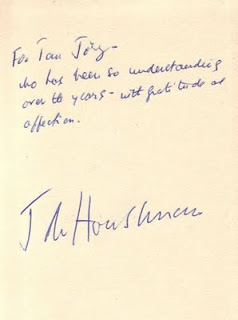

Both BBC Radio 4 and 7 are in the thick of a J. B. Priestley festival, a spate of programs ranging from serial dramatizations of early novels (The Good Companions and Bright Day) and adaptations of key plays (Time and the Conways and An Inspector Calls), to readings from his travelogue English Journey and a documentary about the writer’s troubled radio days. Now, I don’t know just what might be the occasion for such a retrospective, since nothing on the calendar coincides with the dates of Priestley’s birth or death. Perhaps, it is the connection with the 70th anniversary of the evacuation of Dunkirk,

Both BBC Radio 4 and 7 are in the thick of a J. B. Priestley festival, a spate of programs ranging from serial dramatizations of early novels (The Good Companions and Bright Day) and adaptations of key plays (Time and the Conways and An Inspector Calls), to readings from his travelogue English Journey and a documentary about the writer’s troubled radio days. Now, I don’t know just what might be the occasion for such a retrospective, since nothing on the calendar coincides with the dates of Priestley’s birth or death. Perhaps, it is the connection with the 70th anniversary of the evacuation of Dunkirk,