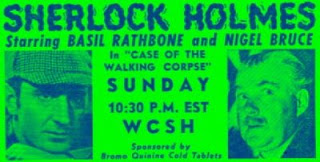

“Salut au monde!” That is a greeting the narrator of Norman Corwin’s “New York: A Tapestry for Radio” extended to the never quite statistically average American listener—anybody tuning in to the nationally broadcast play cycle Columbia Presents Corwin back during World War II. And that is how I, returned again to my old yet ever changing neighborhood in uptown Manhattan, am reaching out to the potentially even more multifarious roamers of the World Wide Web.

“Salut au monde!” That is a greeting the narrator of Norman Corwin’s “New York: A Tapestry for Radio” extended to the never quite statistically average American listener—anybody tuning in to the nationally broadcast play cycle Columbia Presents Corwin back during World War II. And that is how I, returned again to my old yet ever changing neighborhood in uptown Manhattan, am reaching out to the potentially even more multifarious roamers of the World Wide Web.

Why Salut, though? Why go for the highfalutin when something lowbrow like hiya would do? After all, French is not among the languages most closely associated with the Big Pomme. Sure, there is that French lady who greeted the multitudes who came across the big pond to get a bite out of it; but only because she’s made of copper doesn’t make her a coined phrase.

Corwin was not going for the definitive—the single, representative tongue with which to tie up an argument only to contradict it. Symbolic of the promises and failures of the Versailles treaty, the imported salutation is part of a pattern designed for a sonic romancing of immigration central, where nations become nabes and the world’s people are “living side by side so effortlessly, no one calls it peace”—a cosmopolitan locale to which nothing could be more foreign than the homogenous or the homo-logos.

As LeRoy Bannerman describes it, Corwin’s voice collage

advocated world unity, exemplified in the polyglot harmony of New York’s people. It possessed threads taut with the strain of war and the urgency of an all-out effort, symptoms of concern that greatly colored Corwin’s work with tints of patriotism.

The colors in Corwin’s fabric—that crowd-pleasing fabrication of Gotham (what do you call it? Gothamer)—are red, white and blue all right; but when Corwin waves the flag, he does not make difference stand out like a blot on Old Glory. Corwin’s aural tapestry is rich in the variations that the theme demands, distinguished by the “speakers of the foreign and the ancient tongues,” the “conjoined creeds—the Jew, the Christian, the Mohammedan.”

The speech is American, which is to say that it is not exclusively, let alone officially, English or any variation thereof. “Do not mistrust [folks] because of their accent,” the narrator cautions those who stand their ground by calling it common, “for we ourselves might be incomprehensible in Oxford.” The Queen’s English ain’t the English of Queens, New York.

“The people of the city are the main design,” the narrator insists. Seemingly random utterances by speakers nameless to the audience constitute the “individual threads” of an intricately woven fabric whose pattern, unlike the grid formed by the city’s streets, cannot be visually apprehended. “How can you tell, from Seat No. 5 on the plane from Pittsburgh, what goes on here?” Nor can it be comprehended by the unaided ear—at least not by anyone well out of earshot. As I put it in Etherized Victorians, the way to arrive at the design is microphonic, not macroscopic.

The narrator invites “Americans on this wave length” to follow the threads of “interwoven hopes” by “listening acutely” to the peoples of New York City, be they from “German Yorkville” or the “outlying Latin quarters.” Their voices are brought into a meaningful relation through the aid of the radio, of which the main speaker as receiver, amplifier and transmitter is an abstraction.

At the moment—and being in it—it is easy to lose sight of the wireless, even as I walk past Radio City. I feel no need for a hearing aid or a translator. I am a part of a grand, Whitmanesque design, which is both spoken and understood.