When not at work on our new old house—where the floorboards are up in anticipation of central heating—we are on the road and down narrow country lanes to get our calloused hands on the pieces of antique furniture that we acquired, in 21st-century style, by way of online auction. In order to create the illusion that we are getting out of the house, rather than just something into it, and to put our own restoration project into a perspective from which it looks more dollhouse than madhouse, we make stopovers at nearby National Trust properties like Chirk Castle or Speke Hall.

The latter (pictured here) is a Tudor mansion that, like some superannuated craft, sits sidelined along Liverpool’s John Lennon Airport, formerly known as RAF Speke. The architecture of the Hall, from the openings under the eaves that allowed those within to spy on the potentially hostile droppers-in without to the hole into which a Catholic priest could be lowered to escape Protestant persecution, bespeaks a history of keeping mum.

Situated though it is far from Speke, and being fictional besides, what came to mind was Audley Court, a mystery house with a Tudor past and Victorian interior that served as the setting of Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s sensational crime novel Lady Audley’s Secret. The hugely popular thriller was first serialized beginning in 1861 and subsequently adapted for the stage. Resuscitated for a ten-part serial currently aired on BBC Radio 4, the eponymous “lady”—a gold digger, bigamist, and arsonist whose ambitions are famously diagnosed as the mark of “latent insanity”—can now be eavesdropped on as she, sounding rather more demure than she appeared to my mind’s ear when reading the novel, attempts to keep up appearances, even if it means having to make her first husband, a gold digger in his own right, disappear down a well.

As if the house, Audley Court, did not have a checkered past of its own—

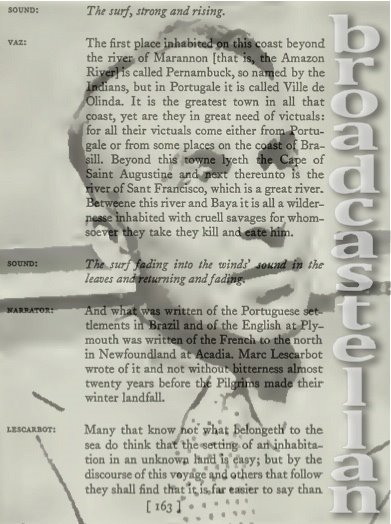

a house in which you incontinently lost yourself if ever you were so rash as to attempt to penetrate its mysteries alone; a house in which no one room had any sympathy with another, every chamber running off at a tangent into an inner chamber, and through that down some narrow staircase leading to a door which, in its turn, led back into that very part of the house from which you thought yourself the furthest; a house that could never have been planned by any mortal architect, but must have been the handiwork of that good old builder, Time, who, adding a room one year, and knocking down a room another year, [ … ] had contrived, in some eleven centuries, to run up such a mansion as was not elsewhere to be met with throughout the county […].

“Of course,” the narrator insists,

in such a house there were secret chambers; the little daughter of the present owner, Sir Michael Audley, had fallen by accident upon the discovery of one. A board had rattled under her feet in the great nursery where she played, and on attention being drawn to it, it was found to be loose, and so removed, revealed a ladder, leading to a hiding-place between the floor of the nursery and the ceiling of the room below—a hiding-place so small that he who had hid there must have crouched on his hands and knees or lain at full length, and yet large enough to contain a quaint old carved oak chest, half filled with priests’ vestments, which had been hidden away, no doubt, in those cruel days when the life of a man was in danger if he was discovered to have harbored a Roman Catholic priest, or to have mass said in his house.

Loose floorboards we’ve got plenty in our own domicile, and room enough for a holy manhole below. It being a late-Victorian townhouse, though, the hidden story we laid bare is that of the upstairs-downstairs variety. At the back, in the part of the house where the servants labored and lived, there once was a separate staircase, long since dismantled. It was by way of those steep steps that the maid, having performed her chores out of the family’s sight and earshot, withdrew, latently insane or otherwise, into the modest quarters allotted to her.

I wonder whether she read Lady Audley’s Secret, if indeed she found time to read at all, and whether she read it as a cautionary tale or an inspirational one—as the story of a woman who dared to rewrite her own destiny:

No more dependency, no more drudgery, no more humiliations,” Lucy exclaimed secretly, “every trace of the old life melted away—every clue to identity buried and forgotten—except […]

… that wedding ring, wrapped in paper. It’s enough to make a priest turn in his hole.

The currency market has been giving me a headache. The British pound is anything but sterling these days, which, along with our impending move and the renovation project it entails, is making a visit to the old neighborhood seem more like a pipe dream to me. The old neighborhood, after all, is some three thousand miles away, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan; and even though I have come to like life here in Wales, New York is often on my mind. You don’t have to be an inveterate penny-pincher to be feeling the pressure of the economic squeeze. I wonder just how many dreams are being deferred for lack of funding, dreams far greater than the wants and desires that preoccupy those who, like me, are hardly in dire straits.

The currency market has been giving me a headache. The British pound is anything but sterling these days, which, along with our impending move and the renovation project it entails, is making a visit to the old neighborhood seem more like a pipe dream to me. The old neighborhood, after all, is some three thousand miles away, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan; and even though I have come to like life here in Wales, New York is often on my mind. You don’t have to be an inveterate penny-pincher to be feeling the pressure of the economic squeeze. I wonder just how many dreams are being deferred for lack of funding, dreams far greater than the wants and desires that preoccupy those who, like me, are hardly in dire straits.