I’ve been having sleepless nights recently, what with this cold and all the rest I am getting throughout the day. It is a testament to my restraint that you still don’t know the half of it. Since I’m not one to crochet or get crotchety, I generally substitute sound sleep for a generous if gentle dose of sound. There’s nothing like canned melodrama to fill the dark hours with images just mute enough not to clash with your pajamas. No thrillers like Inner Sanctum or Suspense, if you please. Too jarring by far! No Fred Allen or Vic and Sade to induce chuckles when it’s snores I’m after. No plays I’d be itching to follow, no tunes I’d be eager to hum. So, I kept my ears peeled for some pop-cultural flotsam that could send me adrift, and presto. The other sleepless night, I finally turned to the kind of fare I rarely try, particularly not when I am in fine fettle. My fettle being decidedly not fit to be in, I contrived to make a late night date with Mary Noble, Backstage Wife.

I’ve been having sleepless nights recently, what with this cold and all the rest I am getting throughout the day. It is a testament to my restraint that you still don’t know the half of it. Since I’m not one to crochet or get crotchety, I generally substitute sound sleep for a generous if gentle dose of sound. There’s nothing like canned melodrama to fill the dark hours with images just mute enough not to clash with your pajamas. No thrillers like Inner Sanctum or Suspense, if you please. Too jarring by far! No Fred Allen or Vic and Sade to induce chuckles when it’s snores I’m after. No plays I’d be itching to follow, no tunes I’d be eager to hum. So, I kept my ears peeled for some pop-cultural flotsam that could send me adrift, and presto. The other sleepless night, I finally turned to the kind of fare I rarely try, particularly not when I am in fine fettle. My fettle being decidedly not fit to be in, I contrived to make a late night date with Mary Noble, Backstage Wife.

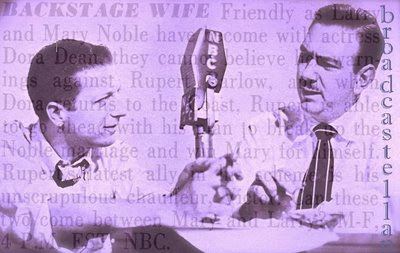

Backstage Wife belongs to that genre known as “soap opera,” defined by James Thurber as a

kind of sandwich, whose recipe is simple enough, although it took years to compound. Between thick slices of advertising, spread twelve minutes of dialogue, add predicament, villainy, and female suffering in equal measure, throw in a dash of nobility, sprinkle with tears, season with organ music, cover with a rich announcer sauce, and serve five times a week.

If you serve that platter past midnight, rather than at lunchtime, the sandwich appears to become more spicy than soggy. After all, what Thurber left out of that list of ingredients is the listener’s imagination, which tends to get saucier once you hit the sheets.

Fodder for radio satirists Bob and Ray’s “Mary Backstage, Noble Wife,” the “story of Mary Noble and what it means to be the wife of a famous star” was on the air for a quarter of a century. A small but sizeable helping of that run is readily available online, namely a storyline involving the scheming Claudia Vincent, a woman who fires shots at man to gain the confidence of another. That the other man is Mary Noble’s husband, Larry, makes Claudia Vincent’s obvious maneuverings all the more delicious.

Not that my taste buds can be trusted in times likes these, but the last thing I wanted was my mouth to start watering. Now my nights are spent wondering about Mary, Larry, Claudia and Rupert, knowing that I shall never hear the end of it, for want of extant chapters. Of course, serial dramas are not about endings. They, like all melodramas, are about the protracted middle, the main courses and the side dishes, about the precariousness of the status quo and all our attempts to stay as we are or get what is presumably owed us. For all its sensational scenes and rhetorical bombast, melodrama is truest to life, far more real, to be sure, than tragedy and comedy. In those aged and unadulterated models of drama, all endings are final; in melodrama, there is plenty of room for doubt, for turns and returns, for the “what ifs” that, I should have known, are keeping me asking for seconds and up for hours.

The current season of Desperate Housewives being so listless you cannot even claim it to have mustered energy enough to jump the shark, I am only too grateful for a bit of cheddar and ham as only those horrid Hummerts could slice it. Now pardon me while I dim the lights. It’s time for my sandwich.

“You will want to know what are my qualifications,” Ring Lardner introduced himself to the readers of his new radio column in the New Yorker back in June 1932. “Well,” the renowned humorist-turned-broadcast critic remarked, “for the last two months I have been a faithful listen-inner, leaving the thing run day and night [ . . .].” Lardner was hospitalized at the time, but he sure knew how to make the most of his misfortune by twisting the dial long enough to squeeze a few bucks out of it, and that at a time when, like today, there were hardly any competitors on the scene but, unlike today, there were millions eager to listen to and read about the radio, its programs and personalities.

“You will want to know what are my qualifications,” Ring Lardner introduced himself to the readers of his new radio column in the New Yorker back in June 1932. “Well,” the renowned humorist-turned-broadcast critic remarked, “for the last two months I have been a faithful listen-inner, leaving the thing run day and night [ . . .].” Lardner was hospitalized at the time, but he sure knew how to make the most of his misfortune by twisting the dial long enough to squeeze a few bucks out of it, and that at a time when, like today, there were hardly any competitors on the scene but, unlike today, there were millions eager to listen to and read about the radio, its programs and personalities.