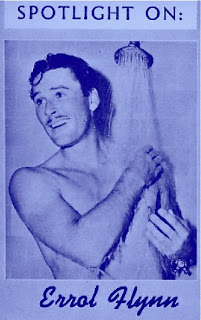

I am taking the passing ash cloud as an occasion to dust off my collection of Cinegrams, a late-1930s to early 1940s series of British movie programs I recently set out to acquire. Immemorabilia, you might call them. Not quite first-rate souvenirs of, for the most part, less-than-classic films like The Return of the Scarlet Pimpernel, or worse. These cheaply printed ephemera were designed—quite pointlessly, it seems—to encourage folks to keep alive their memories of something that may well have been forgettable to begin with. Sure, why not pay a little extra for a few stills of a picture that wasn’t much to look at while in motion? And why not pay still more to keep your “Film Memories” in a self-binding case, with your name on it— in gilt-lettering, no less? That was the offer made to British moviegoers anno 1937, who purchased Cinegram No. 14 to prevent Non-Stop New York from seeming all too fleeting.

Perhaps, I am confusing “forgettable” with “forgotten.” Non-Stop New York which is readily available online, has a lot going for it, quite apart from being a fast-paced romantic vehicle for John Loder and Anna Lee, helmed by Lee’s husband, Robert Stevenson, who would go on to make Flubber and Mary Poppins soar at the box office.

Efficiently if somewhat routinely lensed, this Gaumont-British production might have served as a project for the company’s most notable director, Alfred Hitchcock. Substituting airlanes for tracks, it’s the The Lady Vanishes in the realm of the birds. Except that, in this case, the lady—the young and innocent girl who knew too much—refuses to vanish, which makes the man whose secret she knows all the more eager to see to her disappearance.

The main attraction of Non-Stop New York is not its contrived plot, its charming leads or its rich assortment of goons and ganefs. Rather, it is the film’s setting, the futuristic plane aboard which this pursuit reaches its thrilling climax. It is a large, multi-story aircraft resembling a luxury liner—right down to the outdoor deck on which windblown lovers kiss by moonlight and villains go for the kill. There’s plenty of room for some old-fashioned hide and seek, as passengers are not crowded together but retreat into the privacy of their own cabins. Quite an extravagance, this, considering that the imagined travel time of eighteen hours hardly warrants accommodations fit for on a sea voyage, which mode of transatlantic crossing yet served as a point of reference to the production designers who conceived the vessel.

The main attraction of Non-Stop New York is not its contrived plot, its charming leads or its rich assortment of goons and ganefs. Rather, it is the film’s setting, the futuristic plane aboard which this pursuit reaches its thrilling climax. It is a large, multi-story aircraft resembling a luxury liner—right down to the outdoor deck on which windblown lovers kiss by moonlight and villains go for the kill. There’s plenty of room for some old-fashioned hide and seek, as passengers are not crowded together but retreat into the privacy of their own cabins. Quite an extravagance, this, considering that the imagined travel time of eighteen hours hardly warrants accommodations fit for on a sea voyage, which mode of transatlantic crossing yet served as a point of reference to the production designers who conceived the vessel.

It took Christopher Columbus ten weeks to cross the Atlantic Ocean, Cinegram No. 14 educated its readers. “Today, ten hours seem to be sufficient to complete the same journey.” Set in the seemingly foreseeable future of 1939, Non-Stop New York

anticipates the regular air service which before long [that is, after the end of the wartime air raids that, even in the age of Guernica, purveyors of escapist entertainment did not trouble themselves to predict] will be flying regularly across the North Atlantic and carrying passengers overnight between London and New York. Already survey flights are being carried out by Imperial Airways and Pan American Airways and these flights have shown that such a service is not longer a dream of the fiction writer, but something which to-morrow will be as commonplace as the many daily services of to-day between London and Paris.

The first experimental flights were made in the Summer of 1937. The British company made a series of flights with two of the Empire class flying boats, the “Caledonia” and the “Cambria.” The terminal points of these flights were Southampton and New York and the route followed was by way of Foynes, on the west coast of Ireland across the Atlantic, 1992 miles, to Botwood, Newfoundland. From there the flying boats went to New York by way of Montreal.

In all, 5 two-way crossings were made and these were carried out without incident and with such certainty that they reached the other side of the Atlantic within a few minutes of schedule.

On the last eastward journey the “Cambria” set up an all time record, making the 1992 miles in 10 hrs. 33 min. or at an average speed of nearly 190 m.p.h.

These flying boats will not be used for the Atlantic service when passengers are carried but it is probably that flying boats of the same type, but with greater power and greater ranger will be used. These flying boats may have a cruising speed of 250 m.p.h., and carry 20-30 passengers in a degree of comfort equal to that of the present luxury liner.

With its promise of a jet-setting tomorrow, a title like Non-Stop New York must have sounded thrilling to picture-goers anno 1937, albeit not nearly as thrilling as such a promise is to any present-day passenger awaiting the all-clear for departure at one of Britain’s dormant airports—among them a friend of ours whose plans for a birthday celebration in Gotham are being pulverized by the largest export of a cash-strapped nation to whom volcanic activity appears to be a natural substitute for banking.

Movies like Non-Stop New York and collectibles such as Cinegram No. 14 remind me that, in living memory, long distance air travel was rare and special indeed. They remind me as well of one momentous April morning in 1985—some quarter century ago—when my younger self first boarded a transatlantic flight to the exhilarating and treacherous metropolis that was New York City. Back then, we still applauded the captain who returned us safely to earth; nowadays, we merely moan when we are grounded for whatever strikes us non-stoppers as too long . . .

The currency market has been giving me a headache. The British pound is anything but sterling these days, which, along with our impending move and the renovation project it entails, is making a visit to the old neighborhood seem more like a pipe dream to me. The old neighborhood, after all, is some three thousand miles away, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan; and even though I have come to like life here in Wales, New York is often on my mind. You don’t have to be an inveterate penny-pincher to be feeling the pressure of the economic squeeze. I wonder just how many dreams are being deferred for lack of funding, dreams far greater than the wants and desires that preoccupy those who, like me, are hardly in dire straits.

The currency market has been giving me a headache. The British pound is anything but sterling these days, which, along with our impending move and the renovation project it entails, is making a visit to the old neighborhood seem more like a pipe dream to me. The old neighborhood, after all, is some three thousand miles away, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan; and even though I have come to like life here in Wales, New York is often on my mind. You don’t have to be an inveterate penny-pincher to be feeling the pressure of the economic squeeze. I wonder just how many dreams are being deferred for lack of funding, dreams far greater than the wants and desires that preoccupy those who, like me, are hardly in dire straits.