“I have been trying all I could to get down to the sentimental part of it,” Mark Twain remarked on the “subject of graveyards.” Yet, he concluded, there was “no genuinely sentimental part” to the spectacle we make of the act of decomposing. “It is all grotesque, ghastly, horrible.”

Perhaps it takes a higher degree of sentimentality to find the romance in the morbid; but I am capable of just that. Whenever I travel, I enjoy visiting places of interment, particularly those large necropolises with their temples and statues erected in memory of mortals who, while above ground, played a vital role in the workings of our large metropolises.

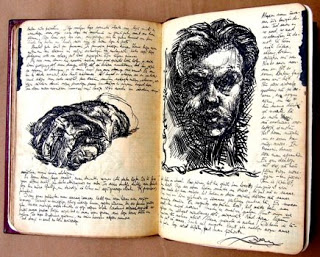

Bankers and bigwigs seem to insist on occupying the largest dwellings in the cities of the dead. There must be some consolation in knowing that, even when six feet below, one can still get folks to look up in admiration. Writers, by comparison, often have modest graves. They, after all, leave their impressions by filling volumes that, however small by comparison to a mausoleum, are apt and ample monuments to their craft. Tombs are largely reserved for those who managed no tomes.

Mark Twain’s own grave is an encasement in point. Last summer, returning to New York City from a trip to Niagara Falls, we had a stopover in the town of Elmira. Since I was in charge of both the map and the guide book, I made sure it was on our way. After all, the humorist from Missouri is buried there. The first thing we did, after securing a room for the night, was to go in search of his final resting place, which we found, eventually, along with that of filmmaker Hal Roach (shown here). However impaired our sense of dimensions after beholding the Falls, the stone (pictured) is less than majestic.

Close to it, though, is a larger monument, about twice as high as the number of feet I presume him to be under, which is precisely the length denoted by the cry of “mark twain” from which Samuel Clemens took his name. The cleverness of the tribute notwithstanding, I wonder whether the writer so honored would have welcomed such a column. Resting assured that monuments are being perpetually erected in the minds of those who read, relish, and recite his words, Mark Twain may well have been better pleased with a more modest disposal, given his attitude toward burials as expressed in Life on the Mississippi:

Graveyards may have been justifiable in the bygone ages, when nobody knew that for every dead body put into the ground, to glut the earth and the plant-roots, and the air with disease-germs, five or fifty, or maybe a hundred persons must die before their proper time; but they are hardly justifiable now, when even the children know that a dead saint enters upon a century-long career of assassination the moment the earth closes over his corpse. It is a grim sort of a thought. The relics of St. Anne, up in Canada, have now, after nineteen hundred years, gone to curing the sick by the dozen. But it is merest matter-of-course that these same relics, within a generation after St. Anne’s death and burial, made several thousand people sick. Therefore these miracle-performances are simply compensation, nothing more.

Besides, he pointed out (quoting a member of Chicago Medical Society, who was an advocate of cremation), “[f]unerals cost annually more money than the value of the combined gold and silver yield of the United States in the year 1880! These figures do not include the sums invested in burial-grounds and expended in tombs and monuments, nor the loss from depreciation of property in the vicinity of cemeteries.”

Mark Twain was born on this day, 30 November, in 1835; he died nearly a century ago and, whatever his views on the matter of tombstones, has well earned his keep at Woodlawn. Here he immaterializes for us in “The Adventures of Mark Twain” (Cavalcade of America, 1 May 1944), the voice being that of Fredric March. In light of Mark Twain’s remarks, I believe he would have approved of the memorial services a cost-effective medium like radio can provide. Radio gets rid of the body but keeps the spirit alive.

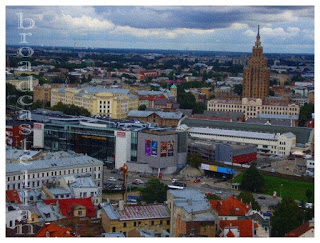

The Latvian National Opera had not yet reopened for the fall season. Little more could be said in our defense. Having enjoyed another organ concert in the Dome, followed by a Russian meal at Arbat, we once again made our way through the old town to pay a visit to the city’s Forum Cinemas, a multiplex boasting the largest screen in Northern Europe. By the end of our stay, we had pretty much exhausted its late-night offerings (the overrated Dark Knight, the enjoyably featherweight Mamma Mia, the horrific Midnight Meat Train featuring Lipstick Jungle’s Brooke Shields, the enchanting art house fantasy The Fall, and the daft but tolerable Get Smart).

The Latvian National Opera had not yet reopened for the fall season. Little more could be said in our defense. Having enjoyed another organ concert in the Dome, followed by a Russian meal at Arbat, we once again made our way through the old town to pay a visit to the city’s Forum Cinemas, a multiplex boasting the largest screen in Northern Europe. By the end of our stay, we had pretty much exhausted its late-night offerings (the overrated Dark Knight, the enjoyably featherweight Mamma Mia, the horrific Midnight Meat Train featuring Lipstick Jungle’s Brooke Shields, the enchanting art house fantasy The Fall, and the daft but tolerable Get Smart).

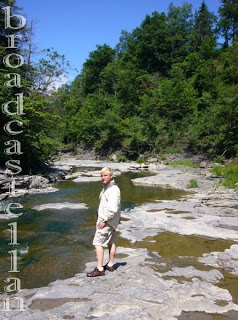

Traveling through Upstate New York on a weekend in summer without having called ahead for reservations is like entering a lottery with money you owe to a loan shark with particularly keen nostrils. It is a heck of a gamble. While not the Vegas type and averse to mixed metaphors, I prefer vacationing without a safety net; but to the one driving and hoping for a bedpost instead of yet another signpost pointing to some rural spot barely traceable on the map it can be rather a pain in the hard-pressed posterior.

Traveling through Upstate New York on a weekend in summer without having called ahead for reservations is like entering a lottery with money you owe to a loan shark with particularly keen nostrils. It is a heck of a gamble. While not the Vegas type and averse to mixed metaphors, I prefer vacationing without a safety net; but to the one driving and hoping for a bedpost instead of yet another signpost pointing to some rural spot barely traceable on the map it can be rather a pain in the hard-pressed posterior. Based on a Broadway stage success of the same title and starring two of the original cast members of the 1909-10 production, The Lottery Man is a clever little farce that tells the story of an impecunious but resourceful college student who offers himself as prize to any woman daring or desperate enough to purchase a dollar ticket, only to realize that he has fallen in love and is jeopardizing a chance at matrimonial happiness by attempting such a money-raising stunt.

Based on a Broadway stage success of the same title and starring two of the original cast members of the 1909-10 production, The Lottery Man is a clever little farce that tells the story of an impecunious but resourceful college student who offers himself as prize to any woman daring or desperate enough to purchase a dollar ticket, only to realize that he has fallen in love and is jeopardizing a chance at matrimonial happiness by attempting such a money-raising stunt. Fleischmanns is a small town. There’s a sign on the road just before you get to it that says POPULATED AREA. Fleischmanns is populated with five hundred people, no more, no less. To a stranger it looks like any other little village in the Catskill Mountains. To a native it’s a special place and every town he doesn’t live in is a nice place to visit but he wouldn’t want to live there—he wants to live in Fleischmanns.

Fleischmanns is a small town. There’s a sign on the road just before you get to it that says POPULATED AREA. Fleischmanns is populated with five hundred people, no more, no less. To a stranger it looks like any other little village in the Catskill Mountains. To a native it’s a special place and every town he doesn’t live in is a nice place to visit but he wouldn’t want to live there—he wants to live in Fleischmanns. While in New York City, I took in a few films I would have otherwise missed (the intoxicating My Winnipeg, featuring 1940s B-movie actress Ann Savage) or given a miss (the eerie Happening, which went nowhere, but worked well as a prolonged exercise in foreshadowing). Of these offerings, The Incredible Hulk was certainly the least, despite the compelling opening sequences shot on location in Brazil. Thereafter, Fantastic Four and X-Men: The Last Stand screenwriter’s Zack Penn’s adaptation of the Marvel strip exhausted itself, like so many of today’s nominal blockbusters, in CGI trickery that, after all these years, still fails to convince me.

While in New York City, I took in a few films I would have otherwise missed (the intoxicating My Winnipeg, featuring 1940s B-movie actress Ann Savage) or given a miss (the eerie Happening, which went nowhere, but worked well as a prolonged exercise in foreshadowing). Of these offerings, The Incredible Hulk was certainly the least, despite the compelling opening sequences shot on location in Brazil. Thereafter, Fantastic Four and X-Men: The Last Stand screenwriter’s Zack Penn’s adaptation of the Marvel strip exhausted itself, like so many of today’s nominal blockbusters, in CGI trickery that, after all these years, still fails to convince me. Having just returned from a trip to Niagara Falls, I was eager to revisit Henry Hathaway’s 1953 technicolor thriller starring Marilyn Monroe. Shrewd, sexy, and sensational, the expertly lensed Niagara is the most brilliantly devised star-making spectacle of Hollywood’s studio era. It has so much going for it that it can afford to be utterly predictable. The Falls are predictable, which does not make them any less exciting. And as much as I enjoy spotting old-time radio performers like the

Having just returned from a trip to Niagara Falls, I was eager to revisit Henry Hathaway’s 1953 technicolor thriller starring Marilyn Monroe. Shrewd, sexy, and sensational, the expertly lensed Niagara is the most brilliantly devised star-making spectacle of Hollywood’s studio era. It has so much going for it that it can afford to be utterly predictable. The Falls are predictable, which does not make them any less exciting. And as much as I enjoy spotting old-time radio performers like the