Now, I am not going to get all sentimental and give you the old “tempus fugit” spiel; but I’d like to mention, in passing, that this post (the 355th entry into the journal) marks the beginning of a third year for broadcastellan. Meanwhile, I am resting with a bad back—in the city that never sleeps, of all places. This afternoon, during an inaugural transatlantic video conference with my two faithful companions back home in Wales, my mind excused itself from my heart and took off in reflections about the ways in which technology has assisted in forging a bond between the US and its close ally across the pond, and the degree to which such tele-communal forgings may come across as mere forgeries when compared to the real thing of an actual encounter.

Now, I am not going to get all sentimental and give you the old “tempus fugit” spiel; but I’d like to mention, in passing, that this post (the 355th entry into the journal) marks the beginning of a third year for broadcastellan. Meanwhile, I am resting with a bad back—in the city that never sleeps, of all places. This afternoon, during an inaugural transatlantic video conference with my two faithful companions back home in Wales, my mind excused itself from my heart and took off in reflections about the ways in which technology has assisted in forging a bond between the US and its close ally across the pond, and the degree to which such tele-communal forgings may come across as mere forgeries when compared to the real thing of an actual encounter.

I was reminded of this again when, a few hours after my chat, I sat, as of old, on a bench by the East River, in a park named after Carl Schurz, a fellow German gone west who likened our ideals to the stars that, however far beyond our touch, yet assist those guided by them to “reach their goal.” In my hand was a signed copy of a newly purchased biography of Edward R. Murrow (by Bob Edwards). It opens with Murrow’s report from the blitz on London, Murrow’s residence during the war.

The broadcasts from London (as featured and discussed here by Jim Widner) did much to enhance the American public’s understanding of the plight of a people, who, due to Hollywood’s portrayal of the British, seemed stuck-up, remote, and about as real as the fog in which Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce waded through some of their adventures. Reports from Britain not only brought home a Kingdom but a concept—the notion of brotherhood untainted by the nationalism whose fervor was responsible for the war.

If not as emotional as Herbert Morrison’s report from Lakehurst during the explosion of the Hindenburg, Murrow’s updates from London were delivered by a compassionate journalist who not only listened in but was a part of what he related while on location. On this day, 21 May, in 1950, British novelist Elizabeth Bowen connected wirelessly with her American audience by speaking via transcription on NBC radio’s University Theater. Bowen referred to her novel The House in Paris (1935) as “New York’s child,” the “fruit of the stimulus, the release, the excitement [she] had received here.” Would she have been able to enter into the feelings of a child lost in a strange house, she wondered, if she “had not just returned from another city, equally new and significant to me?”

There are limits to the connections achieved by the wireless, a controlled remoteness that brings home ideas without ever feeling quite like it. Rather than seeing or hearing, being there is believing. I felt far away during my transatlantic call; but I know I will know what home is now once I get back there . . .

Well, call me a “dirty rat,” but I’ve never paid much attention to this memorial on East 91 Street (or “James Cagney Place,” to be precise), a mere two blocks from where I used to live. The everyday renders much what surrounds us invisible; so, I’m going to make some noise for the old “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” the tribute to whom I now see with eyes accustomed to the green hills of Wales. Say, just how Welsh is the old New Yorker? Taking advantage of the wireless network I am gleefully tapping, I reencountered the

Well, call me a “dirty rat,” but I’ve never paid much attention to this memorial on East 91 Street (or “James Cagney Place,” to be precise), a mere two blocks from where I used to live. The everyday renders much what surrounds us invisible; so, I’m going to make some noise for the old “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” the tribute to whom I now see with eyes accustomed to the green hills of Wales. Say, just how Welsh is the old New Yorker? Taking advantage of the wireless network I am gleefully tapping, I reencountered the  Among the other radio-related finds of the day were fine copies of Earle McGill’s Radio Directing (1940) and Harrison B. Summer’s Thirty-Year History of Radio Programs, 1926-1956 (1971), the latter of which I consulted so frequently while writing my doctoral study on old-time radio. Both volumes sat on the shelves of the Strand bookstore on 828 Broadway, which is well worth a visit for anyone who enjoys browsing for unusual books. A few blocks away, I found a copy of Once Upon a Time (for a mere $4.99); I have long wanted to catch up with this comedy. After all, it is based on Norman Corwin’s radio fantasy (

Among the other radio-related finds of the day were fine copies of Earle McGill’s Radio Directing (1940) and Harrison B. Summer’s Thirty-Year History of Radio Programs, 1926-1956 (1971), the latter of which I consulted so frequently while writing my doctoral study on old-time radio. Both volumes sat on the shelves of the Strand bookstore on 828 Broadway, which is well worth a visit for anyone who enjoys browsing for unusual books. A few blocks away, I found a copy of Once Upon a Time (for a mere $4.99); I have long wanted to catch up with this comedy. After all, it is based on Norman Corwin’s radio fantasy ( Being that this is the anniversary of the birth of Guglielmo Marconi, a scientist widely, however mistakenly, regarded as the inventor of the wireless, I am once again lending an ear to the medium with whose plays and personalities this journal was meant to be chiefly concerned. Not that I ever abandoned the subject of audio drama or so-called old-time radio; but efforts to reflect more closely my life and experiences at home or abroad have induced me of late to turn a prominent role into what amounts at times to little more than mere cameos. Besides, “Writing for the Ear” is a course I am offering this fall at the local university; so I had better prick ’em up (my auditory organs, I mean) and come at last to that certain one of my senses.

Being that this is the anniversary of the birth of Guglielmo Marconi, a scientist widely, however mistakenly, regarded as the inventor of the wireless, I am once again lending an ear to the medium with whose plays and personalities this journal was meant to be chiefly concerned. Not that I ever abandoned the subject of audio drama or so-called old-time radio; but efforts to reflect more closely my life and experiences at home or abroad have induced me of late to turn a prominent role into what amounts at times to little more than mere cameos. Besides, “Writing for the Ear” is a course I am offering this fall at the local university; so I had better prick ’em up (my auditory organs, I mean) and come at last to that certain one of my senses. I appreciate a good hoax; and no hoax is any good unless it wrings from you the admission that you have been had. My common sense yields to the artistry of the con, the handiwork of cheeky tricksters who can cheat you out of your trousers by presenting you a with a hook from which to suspend your disbelief. And however desperately I might try to cover up and recover my composure by juggling an assortment of polysyllables, I am just the kind of fall guy you’d love to be around on April Fools’ Day—or any other day, if you are among those who practice their legerdemain without a license.

I appreciate a good hoax; and no hoax is any good unless it wrings from you the admission that you have been had. My common sense yields to the artistry of the con, the handiwork of cheeky tricksters who can cheat you out of your trousers by presenting you a with a hook from which to suspend your disbelief. And however desperately I might try to cover up and recover my composure by juggling an assortment of polysyllables, I am just the kind of fall guy you’d love to be around on April Fools’ Day—or any other day, if you are among those who practice their legerdemain without a license. No matter how hard I tried to make light of them, by pulling their fingers or sitting on their boots, the colossal statues gathered in the ideological leper colony that is

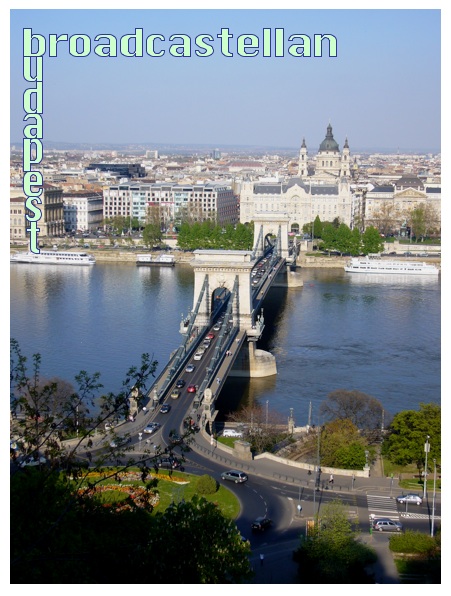

No matter how hard I tried to make light of them, by pulling their fingers or sitting on their boots, the colossal statues gathered in the ideological leper colony that is  Well, that didn’t last long, did it? The wireless connection in our hotel room in Budapest, I mean. It pretty much collapsed after about 48 hours, even though we had paid a small bundle to be online for the week. Not that I find it easy to keep this journal, to keep up with the out-of-date while being out and about on my travels. Our days were filled with taking in the sights; our evenings (and bellies) with goulash, goose liver, and Hungarian wines—from which culinary excesses arose the most curious and vivid dreams. I was paying my respects at the bedside of the

Well, that didn’t last long, did it? The wireless connection in our hotel room in Budapest, I mean. It pretty much collapsed after about 48 hours, even though we had paid a small bundle to be online for the week. Not that I find it easy to keep this journal, to keep up with the out-of-date while being out and about on my travels. Our days were filled with taking in the sights; our evenings (and bellies) with goulash, goose liver, and Hungarian wines—from which culinary excesses arose the most curious and vivid dreams. I was paying my respects at the bedside of the

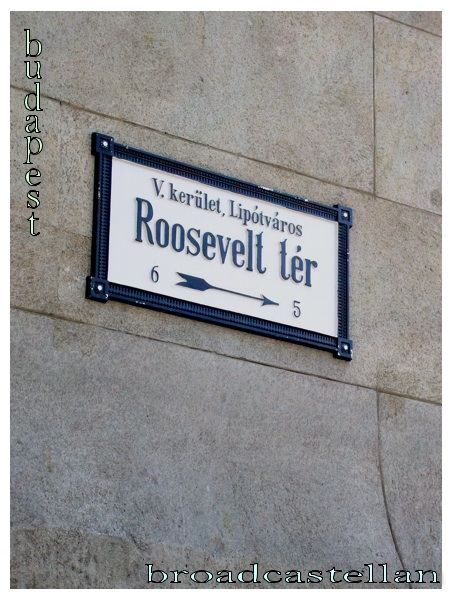

Well, this is it. My last entry into the broadcastellan journal before I’m off to Budapest, from which spot I hope to be reporting back on 12 April with a snapshot of Roosevelt Square, in commemoration of FDR’s death in 1945. Supposedly, our hotel room has wireless access; so I might not have to share my impressions retrospectively (as I have done on almost every previous occasion, after trips to London and Madrid, Istanbul and Scotland, Cornwall and New York City). This time, perhaps, I won’t have to catch up with myself as well as our pop cultural past.

Well, this is it. My last entry into the broadcastellan journal before I’m off to Budapest, from which spot I hope to be reporting back on 12 April with a snapshot of Roosevelt Square, in commemoration of FDR’s death in 1945. Supposedly, our hotel room has wireless access; so I might not have to share my impressions retrospectively (as I have done on almost every previous occasion, after trips to London and Madrid, Istanbul and Scotland, Cornwall and New York City). This time, perhaps, I won’t have to catch up with myself as well as our pop cultural past.