One of the many attractions of Madrid I will make sure not to miss is Picasso’s Guernica (1937), the most famous 20th-century painting in the Reina Sofía collection. A report from the commonplace-turned-combat zone, Guernica is a piece of anti-totalitarian propaganda commemorating the world’s first civilians-targeting air attack: the 26 April 1937 raid on the busy market town of Gernika-Lumo, masterminded by General Franco and carried out by the Condor Legion of Nazi Germany.

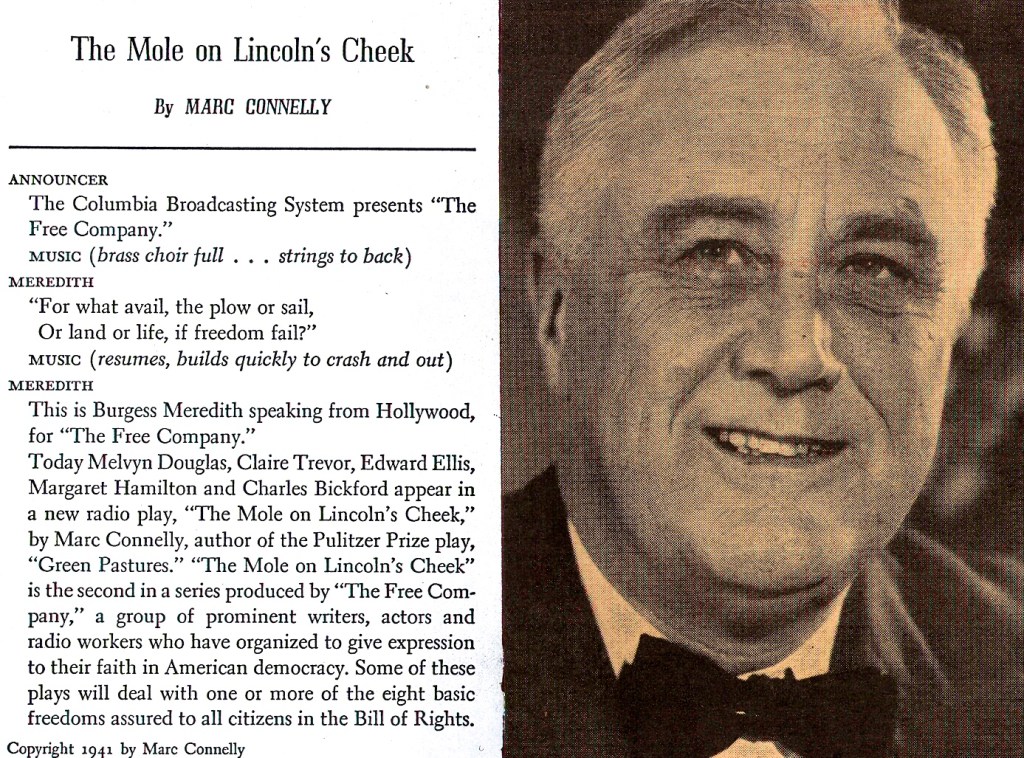

For a long time, the painting was kept out of Spain and was mostly on display at the MoMA in New York City, where, during the Vietnam War, it became a site for vigils held by members of the peace movement, one of whom went so far as to deface it with red spray paint. It was Picasso’s wish that Guernica be returned to his homeland only after the reestablishment of democratic rule. A swiftly executed and brutally manipulative commentary on modern warfare, it invites comparisons to the three best-known American verse plays for radio, Archibald MacLeish’s “Air Raid,” Edna St. Vincent Millay’s “Murder of Lidice,” and Norman Corwin’s “They Fly Through the Air with the Greatest of Ease.”

MacLeish’s “Air Raid,” in contrast to Picasso’s painting, overtly implicates the civilian population, including his radio listeners, castigating them for their supposed ignorance and inertia. As in “The Fall of the City,” MacLeish attacks those falling rather than sentimentalizing their plight. His are bold performances, but his cruel warning turns listeners eager for news into silent partners of war who are asked to “stand by” as they tune in while women and children, refusing to heed warnings of an impending blitz, are being attacked and annihilated:

You who fish the fathoms of the night

With poles on roof-tops and long loops of wire

Those of you who driving from some visit

Finger the button on the dashboard dial

Until the metal trembles like a medium in a trance

And tells you what is happening in France

Or China or in Spain or some such country

You have one thought tonight and only one:

Will there be war? Has war come?

Is Europe burning from the Tiber to the Somme?

You think you hear the sudden double thudding of the drum

You don’t though . . .

Not now . . .

But what your ears will hear with in the hour

No one living in this world would try to tell you.

We take you there to wait it for yourselves.

Stand by: we’ll try to take you through. . . .

Millay’s “Murder of Lidice” recalls the innocent lives of those slain by Richard Heydrich, Deputy Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia, in Lidice. Artistically, the play is indefensible and shockingly inept in its bathos. In Millay’s Grand Guignol of Nazi terror, Heydrich the Hangman, whom the villagers have assassinated, is heard, from the beyond, planning his revenge:

He howls for a bucket of bubbly blood—

It may be man’s or it may be of woman,

But it has to be hot, and it must be human!

Oh, many’s the sweet warm throat he’ll suck.

In “They Fly Through the Air,” Corwin’s narrator goes in search of a language appropriate to the negotiation of art and propaganda. As I point out in Etherized Victorians, the play is a response to the perversion of poetic diction by the fascist cause. Viewed from above, Mussolini reportedly remarked, exploding bombs had the beauty of a “rose unfolding.” Throughout the play, metaphors are at war with plain speech, both in the service of motivating the masses:

What words can compass glories such as we have seen today?

Our language beats against its limitations [. . .].

Our rhythms jangle at the very start.

Our similes concede defeat,

For there is nothing that can be compared to that which lies beyond compare.

You see? We are reduced already to tautologies.

It’s awe does that.

The wonder of it all has set us stammering.

What is the language of war? How does it differ from the idiom of peace? And how shall war—often furious but not always futile—be rendered, recorded, and remembered in words or images? When I look at Guernica this week, I will ask myself these questions. Quite possibly, I will shiver when exposing it to the limitations of my shrinking lexicon.

Well, “gracias, muchisimas!” Thanks to some last-minute planning on my behalf, I’ll be off on a trip to sweltering Madrid, starting next Wednesday. It will be my first visit to continental Europe since I left my native Germany for New York City in 1990; and it has been even longer since last I’ve traveled to a country whose primary language I neither speak nor comprehend. Although I lived just below Spanish Harlem for many years and the majority of my students at City University colleges were Hispanic, I never picked up more than the odd word or phrase. Indolence and impatience aside, my main excuse is that I was too busy appropriating English and promoting it as a common language, the thorough knowledge of which would benefit all who choose to live in the United States.

Well, “gracias, muchisimas!” Thanks to some last-minute planning on my behalf, I’ll be off on a trip to sweltering Madrid, starting next Wednesday. It will be my first visit to continental Europe since I left my native Germany for New York City in 1990; and it has been even longer since last I’ve traveled to a country whose primary language I neither speak nor comprehend. Although I lived just below Spanish Harlem for many years and the majority of my students at City University colleges were Hispanic, I never picked up more than the odd word or phrase. Indolence and impatience aside, my main excuse is that I was too busy appropriating English and promoting it as a common language, the thorough knowledge of which would benefit all who choose to live in the United States. Moving from Manhattan to Mid-Wales was bound to lower my chances of taking in some live theater now and then (not that Broadway ticket prices had allowed me to keep the intervals between “now” and “then” quite as short as I’d like them to be). I expected there’d be the odd staging of Hamlet with an all-chicken cast or a revival of “Hey, That’s My Tractor” (to borrow some St. Olaf stories from The Golden Girls). Luckily, I’m not one to embrace the newfangled and my tastes in theatrical entertainments are, well, conservative. I say luckily because even if you’’re living west of England rather than the West End of its capital, chances are that there’s a touring company coming your way, eventually.

Moving from Manhattan to Mid-Wales was bound to lower my chances of taking in some live theater now and then (not that Broadway ticket prices had allowed me to keep the intervals between “now” and “then” quite as short as I’d like them to be). I expected there’d be the odd staging of Hamlet with an all-chicken cast or a revival of “Hey, That’s My Tractor” (to borrow some St. Olaf stories from The Golden Girls). Luckily, I’m not one to embrace the newfangled and my tastes in theatrical entertainments are, well, conservative. I say luckily because even if you’’re living west of England rather than the West End of its capital, chances are that there’s a touring company coming your way, eventually. Well, the case of the “Piano Man” has been solved, it appears—and another mystery disappears. The denouement could hardly have been more disappointingly prosaic. It tends to be so with mysteries: unraveling them means to explain them away. “Mystery,” as I discovered when I looked up the word in my etymological dictionary, has its roots in muein, “to close the eyes,” as well as mu, a “slight sound with closed lips; of imitative origin.” Mystery is a condition, a state in which the people and things we perceive remain unclear; it is the temptation to discover and the pleasure of delaying the solution.

Well, the case of the “Piano Man” has been solved, it appears—and another mystery disappears. The denouement could hardly have been more disappointingly prosaic. It tends to be so with mysteries: unraveling them means to explain them away. “Mystery,” as I discovered when I looked up the word in my etymological dictionary, has its roots in muein, “to close the eyes,” as well as mu, a “slight sound with closed lips; of imitative origin.” Mystery is a condition, a state in which the people and things we perceive remain unclear; it is the temptation to discover and the pleasure of delaying the solution.