by Harry Heuser

[This is the script for a talk I presented online on behalf of Macclesfield Museums on 19 January 2022. It has been edited and condensed for publication here.]

Silk Town Country Boy: The Life and Work of Charles F. Tunnicliffe RA

Hello, and welcome everyone to today’s presentation. Or, perhaps I should say today’s celebration. After all, we are here to commemorate a big One Two Zero. A one-hundred-and-twentieth anniversary.

Well, it might be a bit late for a display of balloons because the birthday boy in question, whose initials are CFT, and whose names, of course, is Charles Frederick Tunnicliffe, would have had his 120th birthday early last month.

Tunnicliffe was born on the first of December in 1901. He died in February 1979 at the age of 77. That much – and more – you could gather in no time from the rather short Wikipedia page devoted to Tunnicliffe.

It would also tell you that among the awards and distinctions he received in his lifetime, Tunnicliffe was made an OBE in 1978. But, as he told his friend, the nature writer Ian Niall, Tunnicliffe was “not a man for parading in medals.” He found it “incongruous” to be honoured for doing what he loved and for “earning [his] living.”

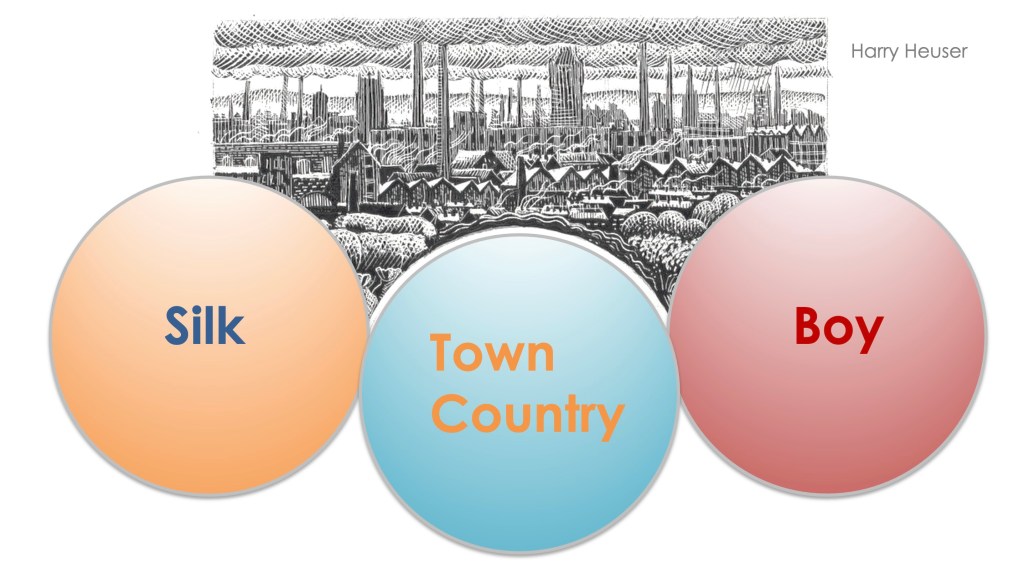

Incongruous. An interesting choice of word. It means “not being in harmony,” not “fitting together.” You might say that about the words in the title of my talk: “Silk Town Country Boy.” Are Town and Country incongruous? Are they incompatible? For that matter, is the work we love – even everyday work – at variance with the distinctions we may or may not derive from it? Like the special and the everyday, town and country are often looked at as worlds apart, even when they are in close proximity. Different attitudes, different lifestyles are associated with life in Town and Country living.

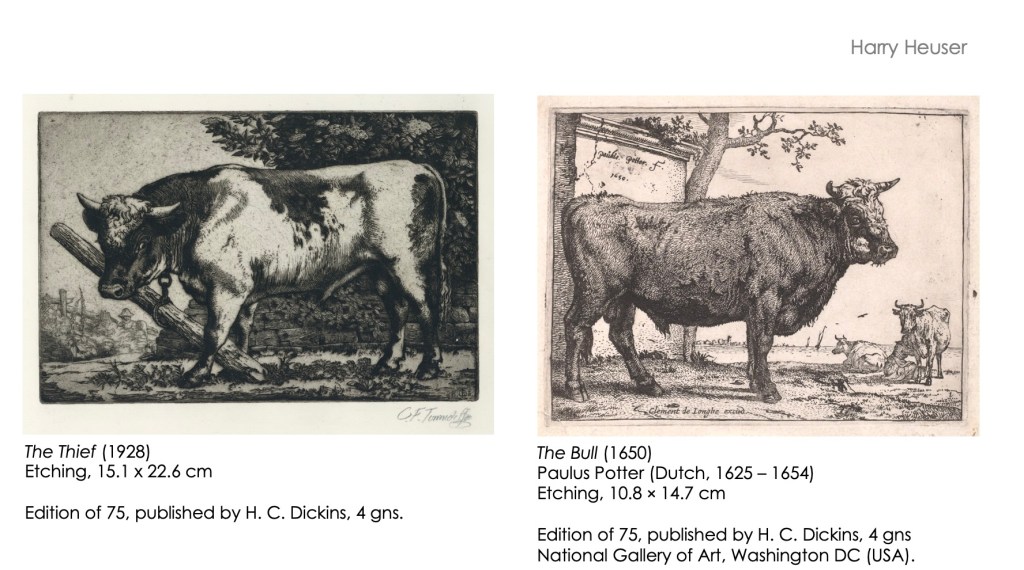

Tunnicliffe produced the image shown here, and most of us who are familiar with his work would not choose this as a representative one. What is Tunnicliffe best known for? And how is he best remembered?

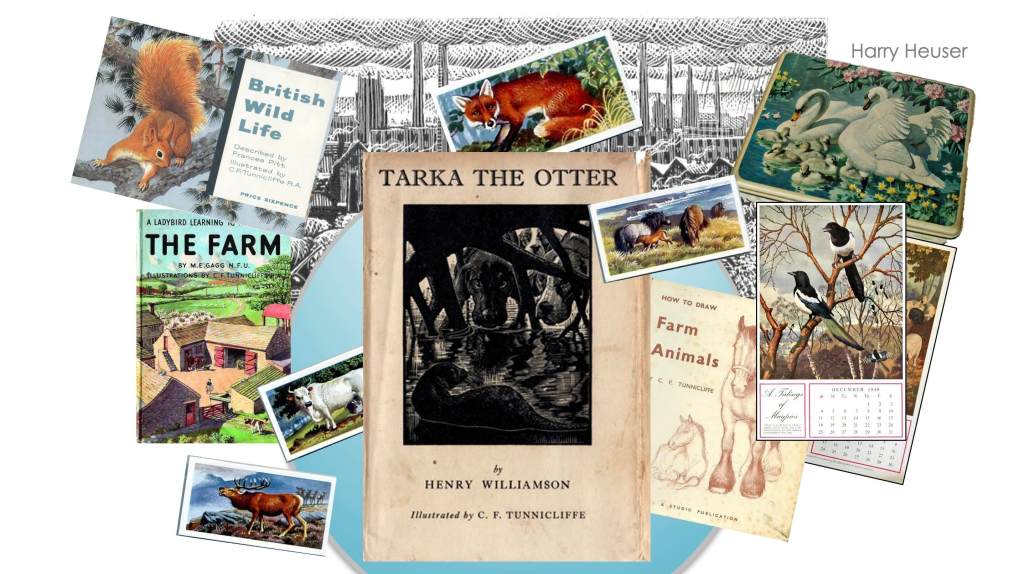

I am sure that many of you have your own Tunnicliffe memories. You may not have met the man, but you might have seen his work, and perhaps own reproductions of it. Tunnicliffe’s work has been multiplied and displayed on calendars, biscuit tins, like this one, from Frears’, dating from 1957 and sold at Christmas; collectible images, such as Brooke Bond Tea cards. Brooke Bond, like Frears, is no more, but survives today as PG Tips; and dozens and dozens of books. Over a hundred of them.

Some were written by Tunnicliffe himself, including his nature journals and his guide How to Draw Farm Animals. Many more were by other writers. Commissions included Under the Sea Wind by marine biologist Rachel Carson, My Friend Flicka by Mary O’Hara, and Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea. However, none of those books were illustrated with wood engravings, which Tunnicliffe gave up altogether in the mid-1950s.

Your favorite books may be among them, the most famous one being Tarka the Otter, by Henry Williamson, with whom Tunnicliffe collaborated as an illustrator on six books.

Even though many of the images he produced are taken from nature, and the British countryside in particular, Tunnicliffe was in fact both town and country. And both are important to the development of his varied and long career. Silk on one side and soil on the other.

Silk town, of course, refers to Macclesfield. And Tunnicliffe was a country boy who lived for many years near and in Macclesfield. That is why Macclesfield Museums have such a fantastic archive of Tunnicliffe’s work and materials related to that work, and why the Museum has organised this celebration.

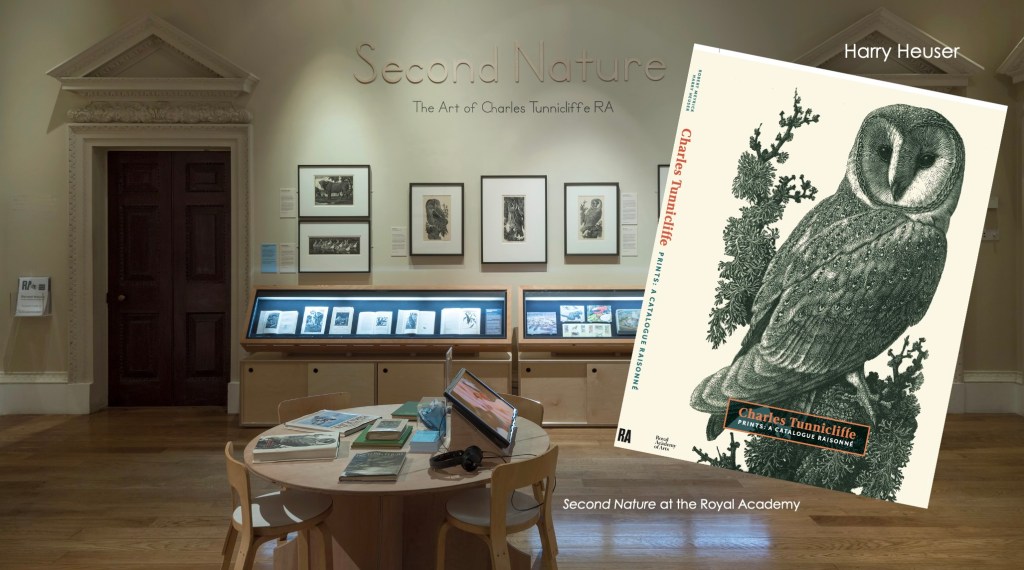

I visited Macclesfield during the research Robert Meyrick and I conducted on a catalogue and exhibition of Tunnicliffe prints at the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

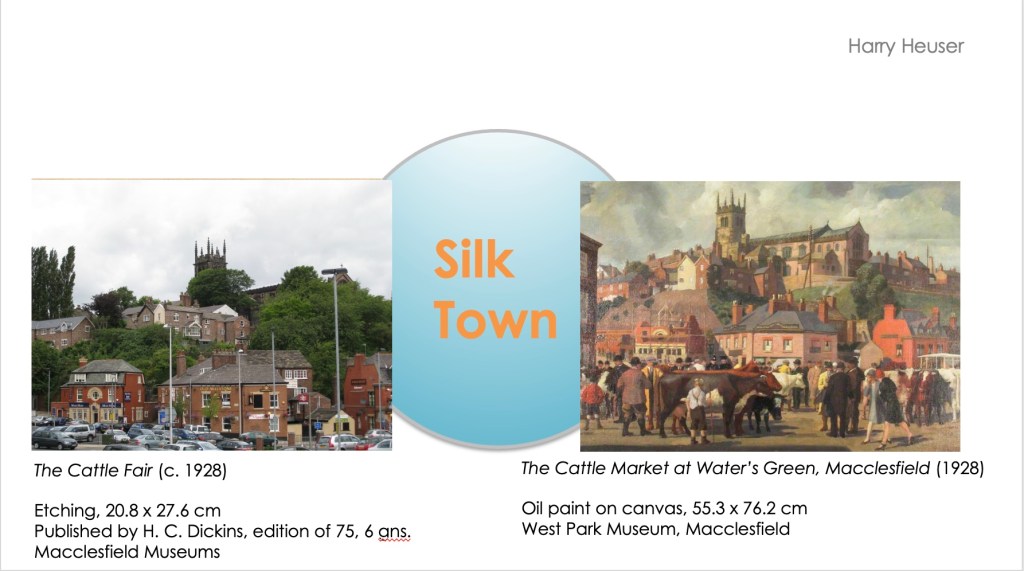

Although Tunnicliffe left Macclesfield for Anglesey in Wales some 75 years ago, he would still recognise the town. While its industry has changed over the years, the view from the town’s railway station, which was backdrop for a 1928 painting, as well as an etching Tunnicliffe produced that same year, is still recognizable.

But by comparing my snapshot to Tunnicliffe’s 1928 painting The Cattle Market at Water’s Green, you not only realise that times have changed, you also are reminded how much an artistic vision can contribute to our view of a place that, to Tunnicliffe, the farmer’s boy, would have been a common place where to conduct business.

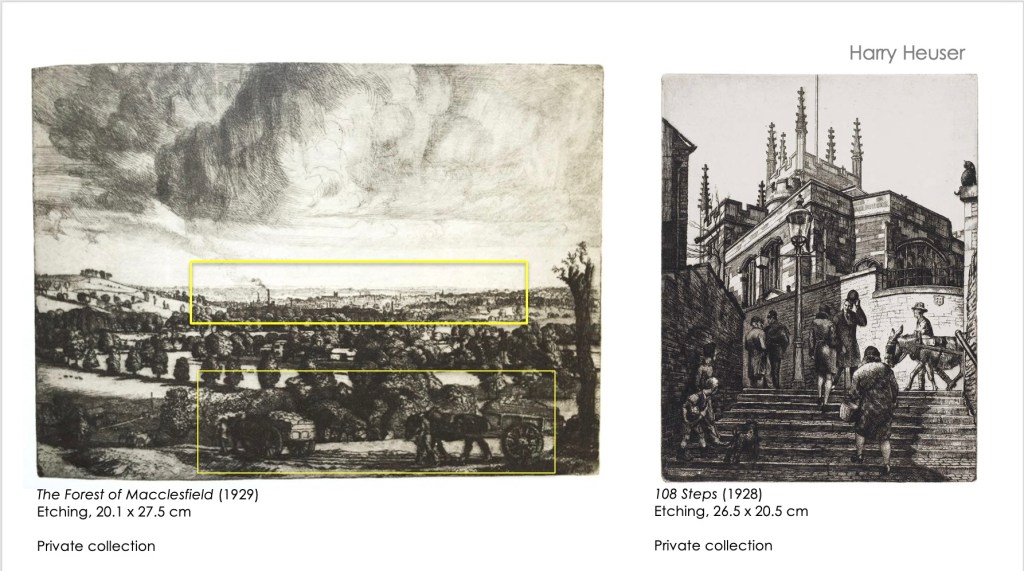

Tunnicliffe’s 1929 print The Forest of Macclesfield (1929) reminds us just how close farming and industry were. Tunnicliffe often called on his friend Nehemiah Rathbone who farmed nearby on the Lee Hills at Sutton. Rathbone’s farmhouse afforded a panoramic view of the Forest of Macclesfield towards Silk Town, two miles north-west where the sky was “always a little murky” from the “chimneys of the silk mills.”

The Forest of Macclesfield was an ambitious subject for Tunnicliffe. On 7 June 1929, he noted in his diary that he had “grounded a plate and after dinner took it up the Lee Hills and commenced to needle the view of Macclesfield and the Cheshire Plain.” The “general outline” was complete after three hours. “There is an enormous lot in it,” he wrote: “Thousands of trees.”

Two days later he was working on the foreground, drawing “three horses and carts filled with stone (carts not the horses)” travelling downhill from the quarry. The needling of the plate en plein air in the Lee Hills was completed over a period of five days.

Tunnicliffe bit the plate on 13 June “and in between the stopping out cleaned the motorbike.” He had not yet taken a proof, but he could see that “the plate itself” did “not promise well.” After some deliberation, he pointed out that “it is not sufficiently organised and the composition is confused.” The plate was refined through several more states over the following two weeks before proofing on five different papers and achieving “great clarity” on Japan paper. It seems that 12 to 15 impressions had been taken prior to December, when Tunnicliffe “added a large tree in the foreground,” which he felt “very much improves the composition.”

It is important to remember that etchings like The Forest of Macclesfield were produced nearly a decade after Tunnicliffe had left rural Cheshire to study art in London. At the Royal College of Art, Tunnicliffe drew and painted from life. He was expected to produce figure compositions. Most of the human figures in Tunnicliffe’s work were farmers, which he continued to observe on the family farm during college vacations.

Following his return to Macclesfield in 1928, a year after his mother had given up Lane Ends Farm, Tunnicliffe observed that his work had fallen into three distinct genres: “pure” landscapes and townscapes, animal paintings and portraits. “As I had ceased to participate in farming,” he wrote in My Country Book, “the focus of my interest was obviously shifting, and I even found myself drawing and painting bits of Macclesfield town.”

Tunnicliffe missed the “stimulating arguments” and discussions about art that he had enjoyed in London. He found a kindred spirit in Mr. Waters, the picture framer in Macclesfield. On 10 October 1929, he noted that Waters wanted him to “do a cheap etching to sell in Macclesfield of the ‘108 Steps.'” Recently married and with a home to furnish, Tunnicliffe added: “Think I shall do it too as extra cash will be very welcome.”

The 108 steps of the title rise steeply from Water’s Green to St Michael’s Church, Macclesfield, and remain a well-known landmark. On the morning of 12 October, Tunnicliffe “took a drawing board and pencil and paper down to Water’s Green and made a rough drawing of the 108 Steps from the cattle auction gates” as well as from other vantage points. In the afternoon, he traced a rough sketch to produce “a more finished drawing for transferring to the plate.” For the next couple of days he was engaged upon needling the copper plate. On 17 October 1929 he bit the plate in acid and pulled his first proof before working further into the plate. He agreed with Waters that they should “try and sell it for one guinea.” When its publication as Churchside, Macclesfield was announced eighteen months later in Fine Prints of the Year 1931, the price was four guineas.

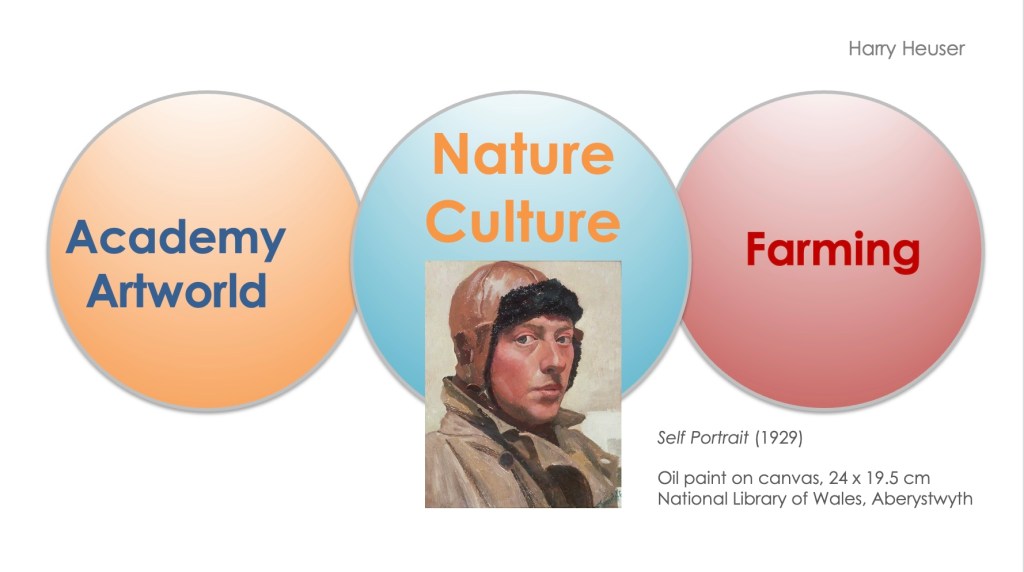

As the old saying goes, you can get the boy out of the country, but you can’t get the country out of the boy. It is sometimes used to suggest that, try as you may, you can’t leave behind what is part of your nature. And that you cannot quite attain what is not your culture: the world of art, the culture of London. Well, Tunnicliffe navigated both those worlds.

In one of his self-portraits, Tunnicliffe shows himself in his motorcycle gear after moving from London, where he had studied art, to Macclesfield, which he had known since childhood. We know that Tunnicliffe was pleased with this likeness. “Raining all day today,” he wrote in his diary on 22 June 1929, “so I spent my time indoors painting a self-portrait in my riding helmet and coat. It is a small canvas and it has come [out] very well.”

As I wrote in my introduction to the Royal Academy catalogue of Tunnicliffe’s prints, the “walls of an art gallery would have struck many of his contemporaries as unlikely a habitat” for someone at home with “wildlife or domestic animals” that, indeed, were Tunnicliffe’s main subjects throughout his career.

In 1954, the contemporary press went so far as to suggest that his election to the Royal Academy had been a freak of nature. “‘Giant-Hands’ Artist is an R.A.,” a Daily Mirror headline ran, referring to Tunnicliffe as “an engraver with outsize hands who specialises in drawing animals.”

Where does Tunnicliffe belong? Where does his art belong?

Unlike the works of many other Royal Academicians, Tunnicliffe’s art does not feature in many studies of twentieth-century art. Is this kind of art too close to nature, perhaps – too imitative – to be deemed high art?

As we have seen, Tunnicliffe’s work did not become most widely known as rare prints and or one-of-a-kind paintings but instead second-hand, as mass-produced ephemera and commercial work. The kind of art that many of us tend to distinguish from “real” art because, unlike in so-called “real” art, commercial art carries messages that are not the words or ideas of the artist but that are superimposed on the image by the advertiser of the products that those images were meant to promote. Even the name Tunnicliffe had to appear in smaller print so that the brand names could be writ large for all the world to see.

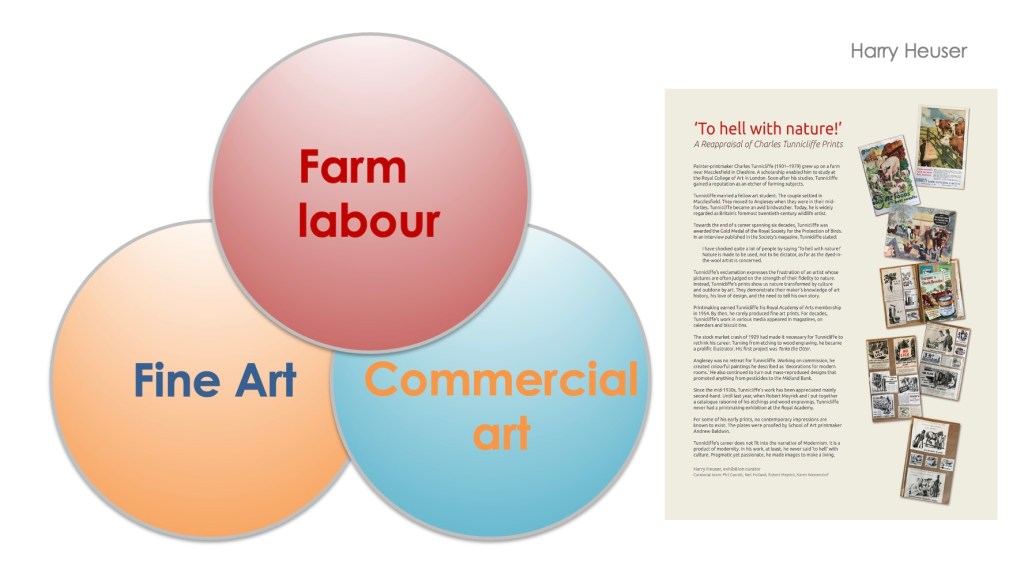

Why did Tunnicliffe, a Royal Academician – a trained artist – produce that kind of work? That is a question I asked in a subsequent exhibition, “To Hell with Nature.” The title is a quotation from Tunnicliffe, a statement he made publicly, in print. It is surprising, even shocking, in its message as well as in its tone.

What did he mean, a country boy so close to nature and so closely associated with the natural world? A man to whom many of us are indebted for introductions to the endangered nature around us – the wildlife of Britain – and to the valuable lesson that we must observe closely in order to understand and learn to care.

Let us return to the beginning. “What urged me to draw and paint in the first place I cannot say,” Tunnicliffe reflected in middle age in My Country Book (1942).

[W]hat is it which compels one man to be a farmer, another a wheelwright, and another a driver of trains?

But what is certain is that my early environment, while not determining that I should be a draughtsman or a painter, greatly influenced my work when I did begin to draw; in fact, it is almost safe to say that it decided its character, for I was born in a Cheshire village and lived and worked on a farm until I was nineteen.

So you see, those years which are supposed to be the most impressionable in one’s life were spent in the heart of the country, in close contact with animals and birds, with farms and farmer and their ways of life, and with all the thousand and one jobs which a farmer has to do.’

In a 1942 article for Studio magazine, he added:

Those years which are supposed to be the most impressionable in one’s life were spent in the heart of the country, in close contact with animals and birds, with farms and farmer and their ways of life, and with all the thousand and one jobs which a farmer has to do.”

Drawing on the surroundings of his youth was second nature to Tunnicliffe. But not all of his juvenile drawings were based on observation of the world immediately around him. The exoticism of the Tarzan stories by Edgar Rice Burroughs were a major source of inspiration. As a teenager, Tunnicliffe read many of the Tarzan books, as he recorded in his 1921 diary.

“My last year at the Art School was one filled with doubt,” Tunnicliffe wrote in My Country Book. “On the farm I was doing a man’s work and at the school the teachers felt that I was now ready for more advanced training. Farming or Art, which was it to be?” The decision was made for Tunnicliffe in the form of an offer that he found too reasonable to let pass:

One mid-summer’s morning, after milking, I was on my way in to breakfast when the postman came down the yard with a long, official-looking envelope in his hand. On opening it I found I had been awarded a Scholarship which would take me to London, and enable me to study for three years at the Royal College of Art in South Kensington.

Not that Tunnicliffe expressed great enthusiasm for this opportunity when he noted it in his diary: “Am booked for London Sept. 28th. Afternoon went blackberrying.” The following morning, Tunnicliffe “went down to school to do some painting” and spent the afternoon “carting manure out on the meadow.’ That job done, he “went down to school again.”

The diary, which was ‘commenced’ on Monday, 18 October 1920, “on the recommendation of […] the assistant master at the School of Art,” who thought – “if he [didn’t] say it” – that young Tunnicliffe had “a head like a riddle,” was clearly not an outlet for the exploration of innermost thoughts.

But, whether he was lacking in confidence or vision, Tunnicliffe could not quite process the prospect of an academic career, even as he was busy producing paintings to apply for additional scholarships.

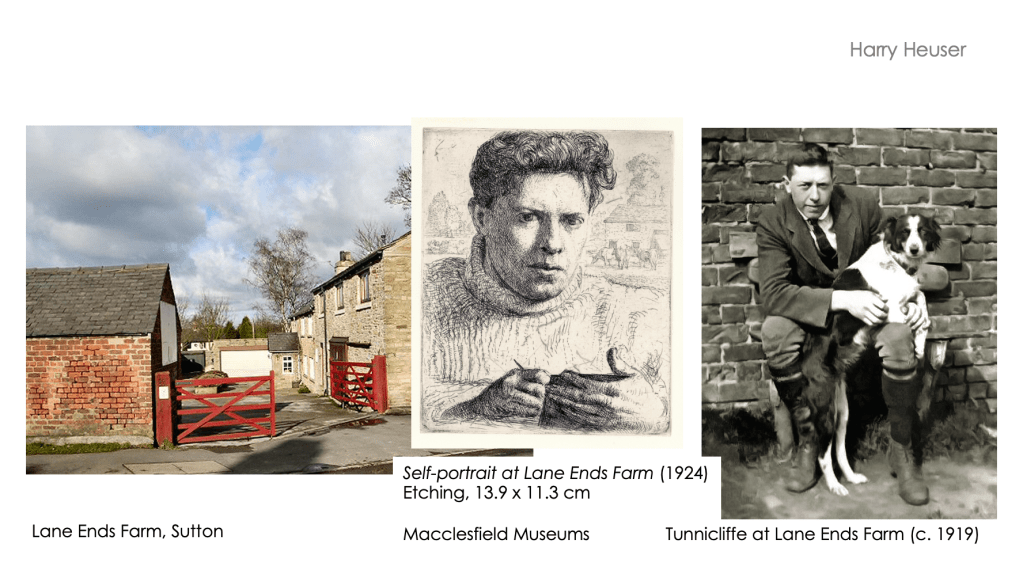

This is the farm, Lane Ends Farm at Sutton, about two miles from Macclesfield.

Tunnicliffe’s father took on this twenty-acre farm when Tunnicliffe was two years Before that, his father, William, had been a shoemaker by trade. It was only after his father was advised by a physician to give up his workshop that he, together with his wife Margaret, a farmer’s daughter, moved from Langley to a farm in the nearby village of Sutton Lane Ends, where, not far from the silk mills of Macclesfield, the couple raised their five surviving children.

Lane Ends was Tunnicliffe’s home until he was 21 years old. And it was the subject – or setting – of many of his early etchings.

‘By the time I was ten years old’, Tunnicliffe recalled in My Country Book, ‘I was up in the morning with the earliest, milking the cows.’ Gradually, ‘more and more work on the farm fell to [his] lot.’ But whenever he found the time, the boy would draw.

When Tunnicliffe was about fourteen, a “sympathetic headmaster” of the village school “facilitated” his entry to Macclesfield School of Art. There, his teachers “did their utmost to help” rather than “endeavour to replace” his “desire to draw cattle, farmers, birds, and animals with their wish for [him] to study the Antique and the Greek and Roman orders of architecture.” Nonetheless, Tunnicliffe conceded, the “study of architecture, perspective, anatomy, and figure-drawing was necessary,” and he accordingly “concentrated on these subjects” during his four years of study, after which he commenced his life drawing studies at Manchester School of Art.

“My last year at the Art School was one filled with doubt,” Tunnicliffe rote in My Country Book. “On the farm I was doing a man’s work and at the school the teachers felt that I was now ready for more advanced training. Farming or Art, which was it to be?” Well, we know how the story turned out. But, in the 1920s, it was certainly unusual for a farmer’s boy to study art.

When we say “study art,” we should keep in mind that Tunnicliffe did not enter the Royal College of Art to pursue fine art, but he started out doing ‘term of architecture.’ Tunnicliffe then transferred to the Painting School. There, he “studiously drew and painted from the life.” Whenever possible, he made use of his background and knowledge to produce “farming scenes.”

“If a composition was required with ‘Summer’ as its subject,” Tunnicliffe recalled, “I could think of nothing but the mowing and carting of hay. ‘Winter’ meant the hungry cattle and the big knife cutting into the hay stacks, a pig-killing scene, or a group of rough-coated colts with their tails to the weather.”

When he graduated with distinction in 1924, Tunnicliffe was persuaded by Malcolm Osborne, Professor of Engraving, to stay on for an extra year to study printmaking under Osborne’s “expert guidance,” as Tunnicliffe later wrote. One of his fellow students, the artist F. C. Dixon, who, like Tunnicliffe, joined the Engraving School in September 1924, recalled him “striding down the main corridor with buoyant and purposeful energy.”

He looked a countryman, rather plump and robustly built, with a roundish ruddy face with slightly protruding eyes that seemed to be looking ahead at some distant goal.

Although Tunnicliffe later pictured himself at work in a number of etchings, this is his only known self-portrait print. There are three recorded self-portraits in oil paint.

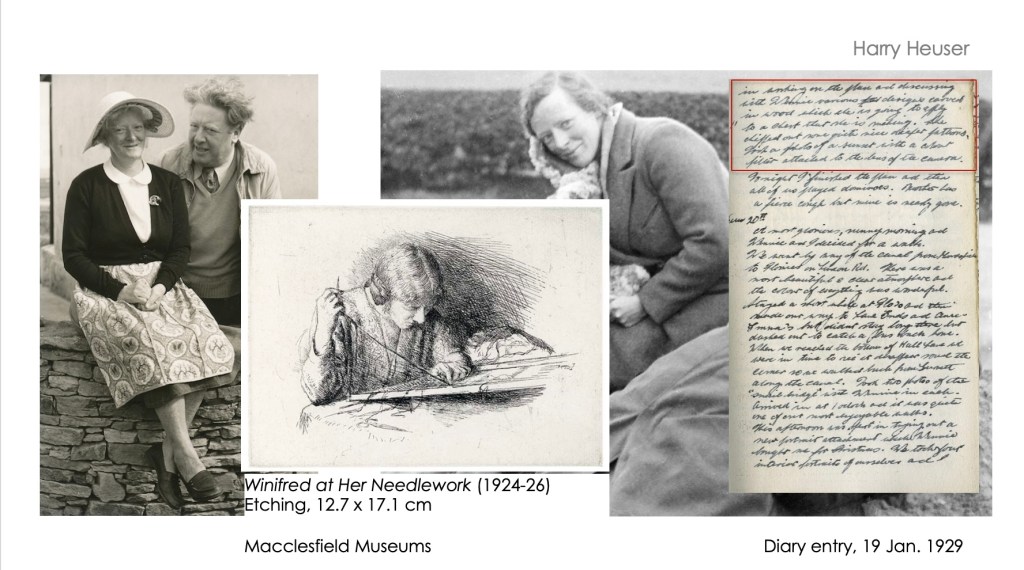

While studying at the Royal College of Art, Tunnicliffe met his future wife, Winifred Wonnacott. She was a fellow student. The two married in 1929. To this day, we don’t quite know how much Winifred Tunnicliffe influenced, supported, or assisted her husband. Given his prolific output, there certainly was collaboration between them. But, in much of Tunnicliffe’s published nature writings, Winifred Tunnicliffe receives scant mention and is cryptically referred to as “W.”

There are references in Tunnicliffe to “Winnie” as an assistance. On 1 January 1929, Tunnicliffe noted in his diary that Wonnacott was visiting for the New Year. The two were not yet married. “Part of her holiday,” Tunnicliffe wrote, “was spent in helping me print from the four plates The Swing Bridge, The Singing Ploughman, The Thief, and The Mowing Machine, all of which Dickins is about to publish.”

On this day, 19 January, in 1929, Tunnicliffe makes mention in this diary of “designs carved in wood that Winnie was applying to a chest that she is making.” In addition to cabinetmaking and pottery, Winifred Tunnicliffe was trained in drawing and painting, bookbinding, leather- and needlework. She was also an arts and crafts educator and taught illustration and graphic design at Woolwich Polytechnic.

Winifred Tunnicliffe was the subject of a number of Tunnicliffe’s portraits, and this one shows her at work. To be sure, such prints were not sold. There are no known contemporary impressions of this portrait. The plate was proofed for inclusion in our catalogue of Tunnicliffe prints.

Winifred Tunnicliffe died in 1969. Her husband survived her by ten years. Next Monday marks the 120th anniversary of her birth.

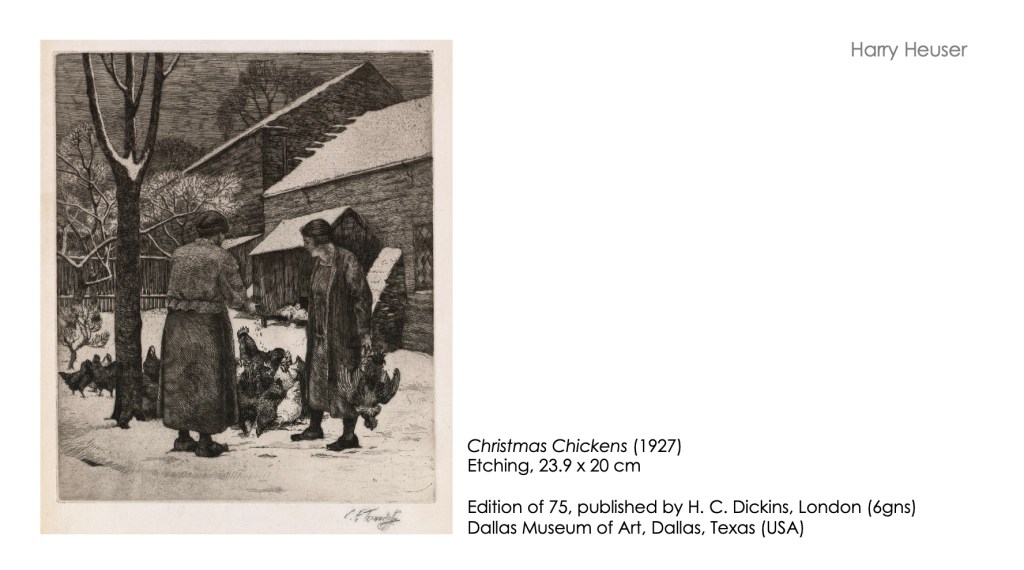

The subjects for prints such as Christmas Chickens (1927) and Feeding the Cattle (1926) are among the many events in the farming calendar that Tunnicliffe described in his diaries. But Tunnicliffe’s early prints – dating from the 1920s – were themselves diaries. Many of them feature members of the family. And they generally show them at work.

The Tunnicliffes were tenant dairy farmers. They also bred pigs. And unless the pigs were sold, they were fattened on kitchen slops and slaughtered. There was no place for sentimentality on the farm. And there is little in Tunnicliffe’s etchings.

You might not see it at first, but the etching To the Slaughter (1925) is a family portrait of life on the farm. The farmer dragging the pig to its death is Tunnicliffe’s father. And the young man who pushes the beast towards the block is Charles Tunnicliffe himself. They are assisted by the master butcher of Mill Street, Macclesfield, James Etchells, who places a pail under the table to collect the blood after the throat has been cut. Tunnicliffe’s younger sister, Dorothy (Dolly), stands in the doorway. She is probably holding a cauldron of boiling water to scald the carcass and scrape away the bristles.

“How they would struggle!” Tunnicliffe remembered such slaughter scenes. “In its dying struggles, it required at least two strong people, besides the butcher, to hold the pig on the bench.” Letting a pig bleed to death was thought to improve the meat. Death usually took two minutes after “sticking.”

Using Tunnicliffe’s teenage diaries we were not only able to describe the events surrounding the slaughter of The Stuck Pig, but we identified all four characters: the pig has been expertly “stuck” in the throat and ‘bled’ into a pail by James Etchells, master butcher of Mill Street, Macclesfield; the artist, cloth cap worn backwards, assists his father in holding down the beast as it bleeds to death. Tunnicliffe’s sister Dolly puts all her strength behind a rope that draws back the foreleg of a pig to keep it still and to open the wound.

These etchings were not commercially desirable in the 1920s. Only a few lifetime impressions were taken. Afterwards, the plates lay unpublished.

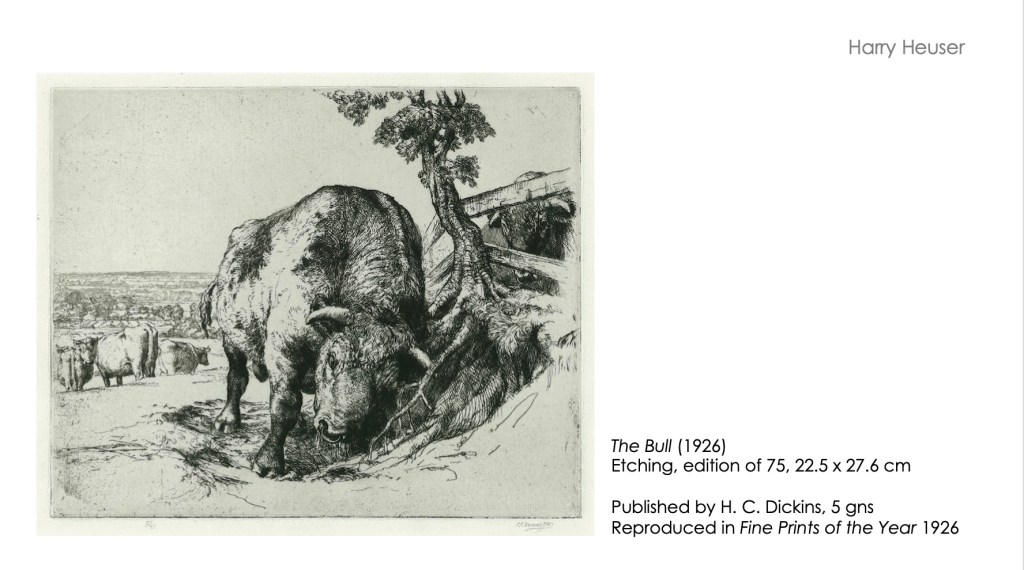

Tunnicliffe spent much of his boyhood working with cattle. He wrote more about the bull – his character and unpredictability – than about any other farm animal. “If you must draw him,” he cautioned, “see that he is chained up, or that there is a good strong fence between you and him.”

The “Thief” in question is a Shorthorn bull. Despite the heavy log chained about its neck, it has broken free of its enclosure. The farmer, whom you can spot in the back, is keeping his distance. As one contemporary reviewer pointed out, the bull “watches the spectator with a suspicious and rebellious eye.”

“When I was a boy,” Tunnicliffe wrote,

one of my favourite pastimes was to imitate the low bellowing of a bull, and then to watch the effect on one in the next field. Up would go his head, as he gave an answering bellow, and soon he would be clearing all the cows of his herd away from the vicinity of the fence, behind which I was concealed. Then, uttering low, throaty growling, he would advance, intermittently stopping to paw the ground with his fore-feet, and sending turf and sods flying into the air. With bloodshot eyes, saliva dripping mouth, and nose close to the ground, he would look an awesome sight. Arriving at the fence, and not sighting his antagonist, he would indulge in a goring orgy, tearing at the roots of the hawthorns with his horns and feet, and making the most horrible noises.

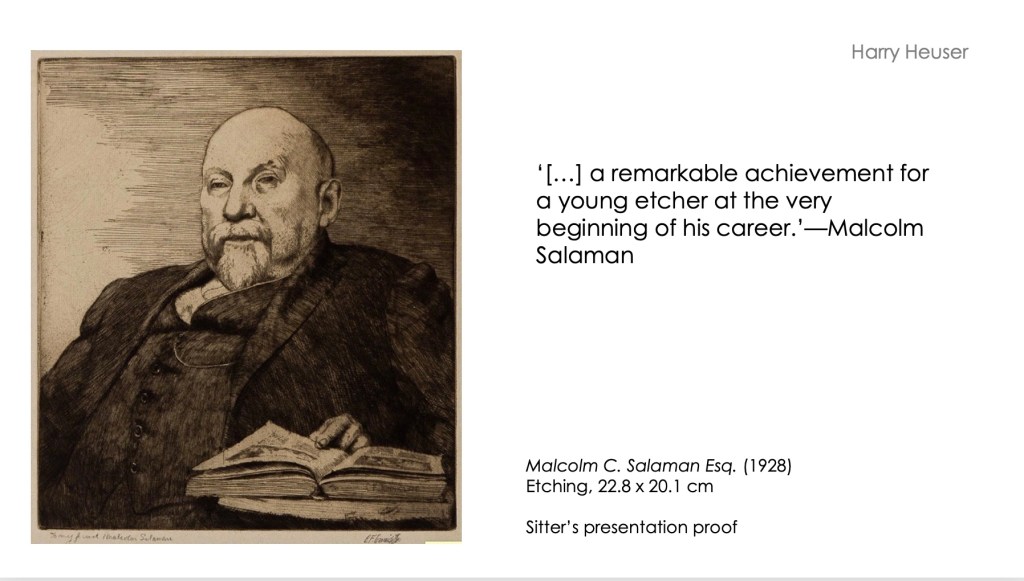

Writing for the magazine Studio in 1927, Malcolm Salaman called Tunnicliffe’s The Bull a “remarkable achievement for a young etcher at the very beginning of his career….”

The sunny charm of the landscape, so delicately bitten for its distant recession, and the grazing cattle grouped on the sloping ground, these were well enough, though not of themselves particularly new; but the great vivid beast that so dominantly yet so harmoniously held its place in the picture, surely this was stamped with at least the promise of a master.

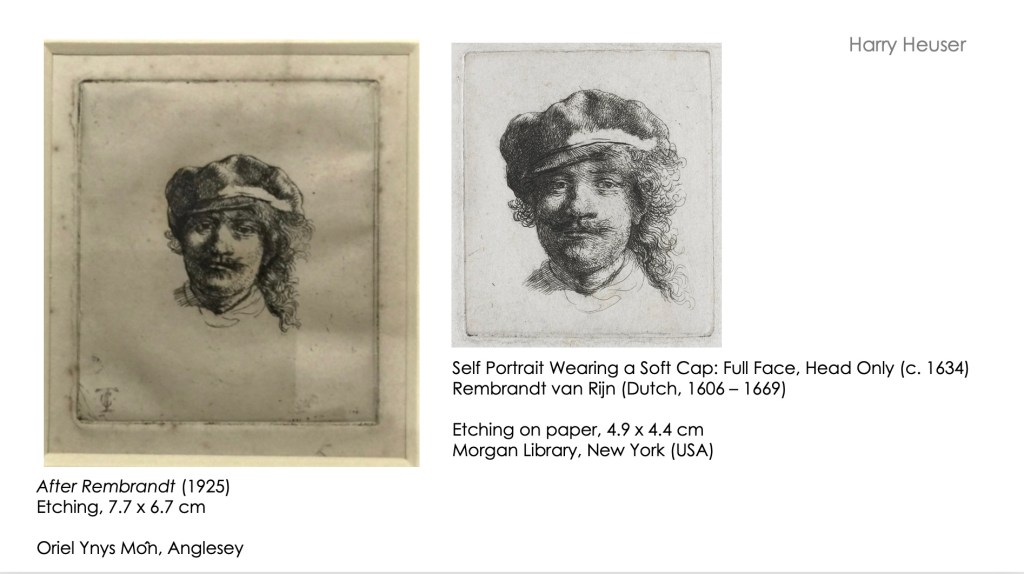

Let us look at Tunnicliffe’s influences in further detail. In My Country Book, Tunnicliffe claimed that The Harvesters was his second etching. It is unlikely, however, that such a large and technically accomplished etching should immediately follow his copy After Rembrandt “Self-portrait Wearing a Soft Cap.” Focusing on prints he considered to be among his greatest achievements, the artist, it seems, was already abridging his oeuvre for posterity.

Tunnicliffe joined the Engraving School during his fourth year at the Royal College of Art (1924–25) and “soon became absorbed in the art of etching.” As he recalled in My Country Book, the “first exercise was to copy a head by one of the masters of etching.” His tutor, Malcolm Osborne, RCA Professor of Engraving, commonly assigned a Rembrandt portrait to those he considered his best draughtsmen and a Van Dyck portrait to students he deemed less able.

Ken Broughton, secretary and founder member of the Charles Tunnicliffe Society has suggested that the frieze-like composition of Harvesters is modelled on the etching Returning from the Field by German painter-printmaker Fritz Boehle (1873–1916). Like The Harvesters, it depicts three male farmhands, two with pitchforks over their shoulders, and a female with a lunch basket on her forearm. Whereas Boehle shows workers leading oxen, Tunnicliffe’s labourers walk alongside two dapple-grey Percheron horses. Tunnicliffe owned a copy of the English-language edition of Rudolf Klein’s 1910 monograph Fritz Boehle in which Returning from the Field is reproduced.

Starting out, Tunnicliffe had been encouraged to see himself as a printmaker in the tradition of Rembrandt and Dürer, whom he considered his own “masters.” Tunnicliffe’s “first exercise” as a student at the College was to “copy a head by one of the masters of etching’, for which he chose a ‘small self-portrait by Rembrandt.”

For Tunnicliffe, as for most of his fellow printmakers, the concern was that “purchasers” simply did not buy, at least not at prices that would convince artists to supply the demand for that “kind of decoration.” In Britain, the market for contemporary prints – or the “racket,” as Kenneth M. Guichard termed it – had peaked just at the time when Tunnicliffe joined the Engraving School during his fourth year at the Royal College of Art in 1924–25.

Reviewing Tunnicliffe’s early works, Laver recognised Tunnicliffe’s debt to Rembrandt and his followers by declaring The Kestrel to be “reminiscent of some of the early Dutchmen.” On 9 February 1929, Tunnicliffe visited the Exhibition of Dutch Art 1450–1900 at the Royal Academy of Arts. Arriving at 9.30 am, he “had a quite good look at the more important works before the crowds came in.” Vermeer appealed to him “most of all together with a few of Rembrandt’s portraits.”

For six books by Henry Williamson alone, Tunnicliffe produced more than 140 wood engravings over a period of just two years. Tunnicliffe’s output was vast, but his range of subjects was limited. “I don’t illustrate a book if I do not know the material,” he reasoned. This made work on Williamson’s The Star-born a challenge. The book was a “celestial fantasy,” and the author’s instructions left Tunnicliffe “completely baffled.”

Tunnicliffe received £50 for providing sixteen full-page illustrations and numerous small decorations for tail pieces of chapters. He insisted on retaining ownership of the blocks. This enabled him to sell his prints separately.

The last book to feature Tunnicliffe’s wood engravings was a 1949 edition of Wild Life in a Southern County by Victorian nature writer Richard Jefferies. Afterwards, Tunnicliffe used scraperboard and line drawing for monochrome illustrations. Working with a small graver had become a strain on his eyes.

The prints displayed on this wall are Tunnicliffe’s response to the collapse of the fine prints market. His etchings “ceased to sell” after the crash of 1929, Tunnicliffe recalled. He “had to cast about for other means of making a living.” The “slump” proved a boon for Tunnicliffe. It led to the success he enjoyed as an illustrator. The career change was encouraged by Tunnicliffe’s artist wife. Winifred Tunnicliffe had read Tarka the Otter by Henry Williamson and thought it would be a “marvellous book for illustration.”

Tunnicliffe submitted four aquatints to Williamson’s publisher. He did not realise that they were too costly to reproduce. Tunnicliffe was asked to work in wood engraving instead. It was a medium in which he had “only dabbled” before.

“He knows his subjects from intimate personal experience, knows them inside out, so to speak,” Salaman wrote in 1927, “and whatever beauty pictorial interpretation may discover in them he recognises instinctively, and with it the traditional dignity and sentiment inherent in the labourers of farm and field.”

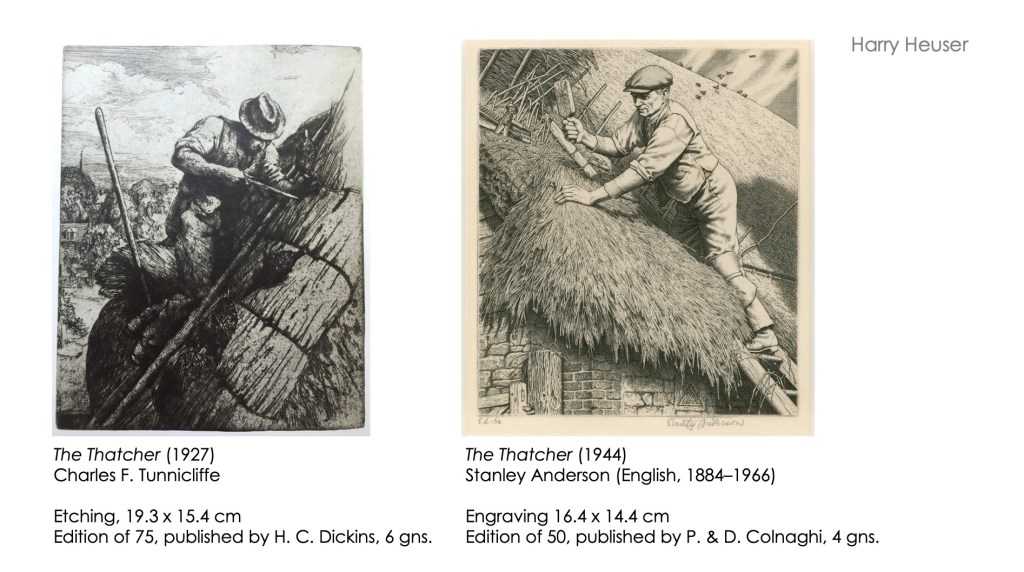

The nature of much of what Tunnicliffe did for a living defies the term “art,” at least in a Romantic or Modernist sense. For instance, his contemporary painter-printmaker Stanley Anderson, rejected the term “artist,” arguing that the “old assignments,” such as “stone-carver, painter, engraver, illuminator,” or “cabinet maker” were “free from snobbery.” Anderson, nearly 20 years his senior, appreciated Tunnicliffe’s diligence and commitment. In 1936 Anderson voiced his support for Tunnicliffe’s nomination for an associate membership of the Royal Academy. For Tunnicliffe, as for Anderson, self-expression was not a chief aim.

The Macclesfield Museum archive holds much of the correspondence that exists from Henry Williamson to Tunnicliffe concerning their collaboration. Among the letters are 100s of drawings that are proposed designs for wood engraved illustrations, sent to Williamson and returned to Tunnicliffe covered in the author’s annotations. Six full-page wood engravings, cut for Tarka the Otter but not included in the publication, were discovered in the course of our investigations.

Tunnicliffe came to appreciate birds in the early 1930s while working on illustrations for Henry Williamson’s nature stories. The author made critical comments on Tunnicliffe’s proposed illustrations. He was dissatisfied with some of Tunnicliffe’s designs. Williamson’s snide remark “see a barn owl somewhere Mister Tunnicliffe” encouraged Tunnicliffe to study birds more closely. For his efforts, Tunnicliffe was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.

Studies of dead specimens were essential to Tunnicliffe’s compositions. Pages from Tunnicliffe’s sketchbooks were exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1974. Initiated by the Welsh artist Kyffin Williams, Bird Drawings was Tunnicliffe’s first and only solo show the Academy staged in his lifetime. He had been a full member since 1954.

Uncertain about the drawings, the Academy consulted an ornithologist who vouched for their accuracy. The drawings were arranged according to family, genus and species. Tunnicliffe had lent them only reluctantly. They ended up portraying him as an imitator of nature.

Bird Drawings by C. F. Tunnicliffe RA – which ran from 3 August to 29 September 1974, was Tunnicliffe’s last – and, until the show created by Robert Meyrick and myself in 2017, the only – solo exhibition at the Royal Academy. The show was devoted almost exclusively to the post-mortem drawings that Tunnicliffe had produced on Anglesey, with the assistance of his wife whose influence on and contributions to Tunnicliffe’s work have remained largely unacknowledged.

Some three hundred of those drawings went on display in the Academy’s Diploma Galleries. So vast was Tunnicliffe’s output that Williams initially suggested the display of one thousand works, a proposal the Academy rejected as unfeasible.

Specimens of Tunnicliffe’s measured drawings and pages from his sketchbooks were arranged, with the assistance of the ornithologist Bruce Campbell, according to family, genus and species. Before committing to this exhibition, the Academy consulted Gavin Bridson, the Librarian of the Linnean Society, who stated that although Tunnicliffe’s drawings were highly competent and well observed, the Natural History Museum had hundreds of drawings of equal skill. Bridson expressed the view that Tunnicliffe’s success was based on the popular presentation of his work, such as book illustrations and the Brooke Bond Tea cards series. From an ornithological perspective, the drawings were of little value, Bridson held, as the modern study of birds was carried out from skins rather than drawings. He also doubted whether drawings of dead specimens would attract a public that, in his view, preferred a naturalistic representation.

The exhibition attracted a modest audience and, unbeknown to Tunnicliffe, “incurred a large proportionate deficit.”

Over 200 large sheets of postmortem studies are held by Oriel Môn on Anglesey. They show Tunnicliffe’s scientific engagement with animal anatomy, bird plumage as it varies male to female, season to season, and youth to maturity, as well as his work in the field observing behaviour and flight patterns.

Tunnicliffe’s exclamation “To hell with Nature!” highlights the artist’s frustration with market demands and the widely held attitudes toward his work as mimetic and forensic. One contemporary reviewers deemed Tunnicliffe’s “bird paintings” “unusual” for being “both accurate and decorative.” But the chief criterion with which critics judged Tunnicliffe’s prints was fidelity.

“Most of the modern wood-cuts of birds […] portray what can only be termed as monstrosities,” a reviewer of Mary Priestley’s A Book of Birds opined in 1937, “and one can scarcely imagine any genuine bird-lover looking at them without […] wishing that we might have a Hitler to order their abolition.” By comparison, Tunnicliffe’s prints were “really like birds, not only in detail but in their characteristic and natural poses.”

The critique appeared in the magazine British Birds and was aimed at an audience to which Tunnicliffe increasingly appealed, even as he continued to produce nature themed images for advertising and book illustration. While a specialised audience was better able to discern the accuracy with which Tunnicliffe rendered the natural world, critics, historians and curators largely neglected to engage with his work as art.

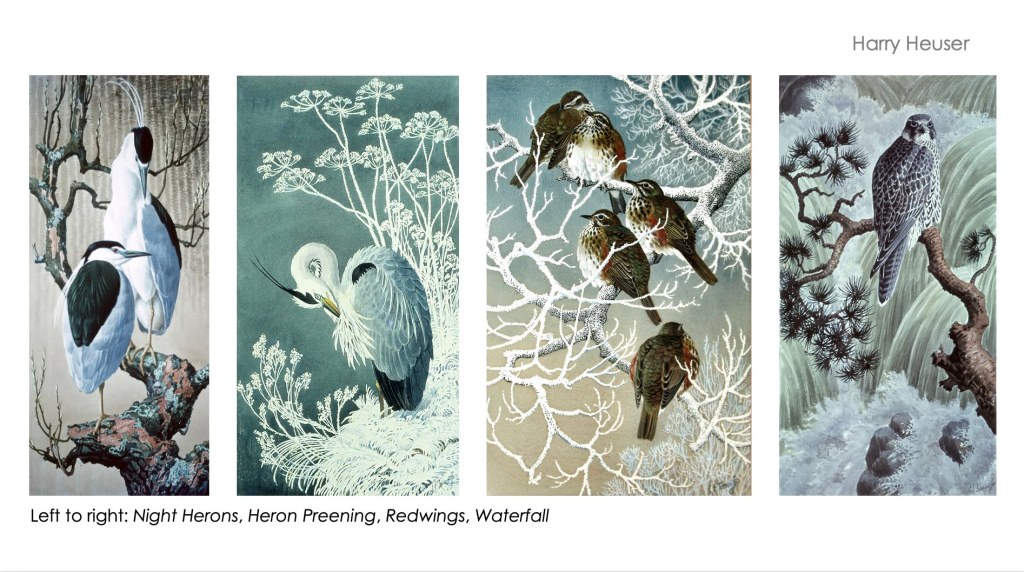

What is the relationship between observation and art? Between imitation and creation? Between science and art? Tunnicliffe did not just re-create what he saw. He also made artistic choices. Tunnicliffe’s watercolours threw light on the compositional devices he used in his wood engravings for The Sky’s Their Highway and Book of Birds.

They also tell us of his admiration for compositions found in Chinese painting and Japanese prints. “Nature is a master pattern maker,” Tunnicliffe wrote in My Country Book, “capable of designs far more wonderful than anything that I could have invented.” Nature was not his only guide, however. For his decorative prints and paintings, Tunnicliffe chose flattened forms over illusionistic techniques. To his readers, he recommended the study of Chinese, Japanese and Persian artists. For his bird portraits, Tunnicliffe also relied on the work of fellow bird artists. He admired The Birds of America by the naturalist John James Audubon.

A “picture is a purely man-made thing,” Tunnicliffe declared in later life. To “let nature dictate is impure.”

Many of the illustrations for Tunnicliffe’s books were derived from sketchbook drawings of his family farm and neighbours’ farms as well as the surrounding countryside. Tunnicliffe not only introduced many children, and adults, to the natural world, he also shared how to draw them. In some of his books, such as Bird Portraiture (1945) and How to Draw Farm Animals (1947), he demonstrated to his younger readers how it was done. All the same, he argued in Bird Portraiture (1945) that it would be “foolish to attempt to lay down any hard and fast rules for the practice of bird-painting.” Instead, in How to Draw Farm Animals, he insisted that “the only practical and sure foundation’ was the ‘close study of living creatures.”

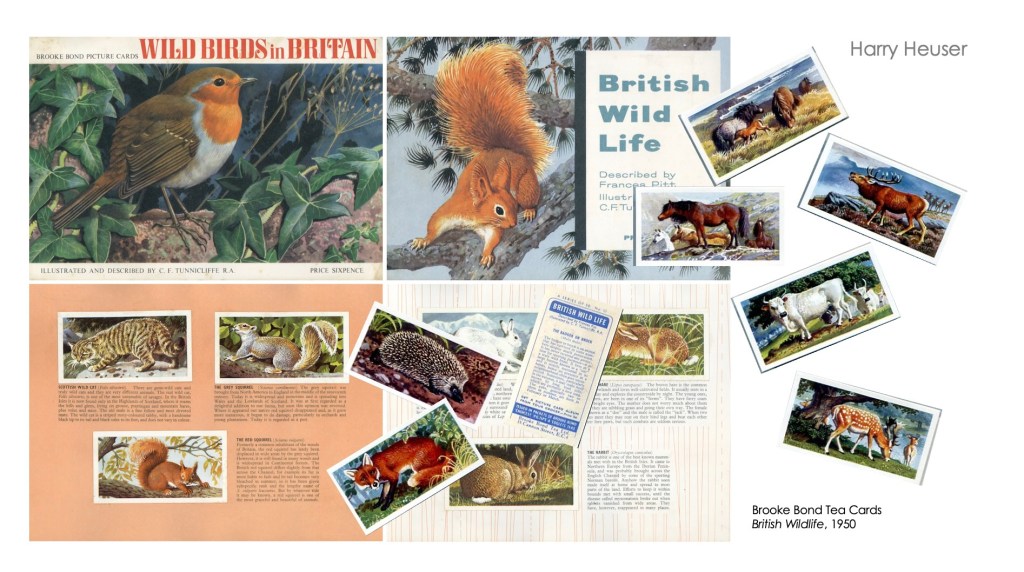

In the 1950s and 1960s, Tunnicliffe’s series of collectible cards for Brooke Bond Tea – British Wild Life (1958); Bird Portraits (1957); Wild Birds in Britain (1965) – were swapped in school playgrounds across Britain. Image were also reproduced as wall charts for display in schoolrooms. Tunnicliffe’s lucrative contract to illustrate 100s of Brooke Bond Tea collector cards required that he write short descriptions of each animal to explain its characteristics, habitat and behaviour.

Series of picture cards offered in the interests of education and wildlife conservation by Brooke Bond, given with Brooke Bond Tea, Brooke Bond Pure and French Coffees, and Crown Cup Instant Coffee. Some, such as Tropical Birds (1961) are more exotic. Most of Tunnicliffe’s pictures were only ever appreciated as reproductions.

For over four decades, Tunnicliffe’s pictures advertised soap, cruise lines, dog food, stout, fertiliser and the Midland Bank. The absence of any message or agenda opened Tunnicliffe’s images to a market beyond the art scene. In advertising, the messages were supplied by the companies that sought Tunnicliffe’s work, be it to promote Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) or the manufacturers of Dairy Flyspray containing DDT.

After the collapse of the market for fine prints during the Depression, Tunnicliffe survived as an artist by working on demand and appealing to a broad audience. Printmaking played a key role in this. It had brought Tunnicliffe critical acclaim initially, but it also enabled this shift from academic to commercial work.

Commissions for Bibby’s animal feeds and Boots the Chemist were often accompanied by texts provided by Tunnicliffe. He writes of the animals’ distinguishing features, their character and behaviour, and their habitats. This informed my writing on later prints as well as his wood engravings for Richard Jefferies and Mary Priestley books. Tunnicliffe’s personal scrapbook of commercial work from the 1930s to 1960s is held in a private collection in Cardiff.

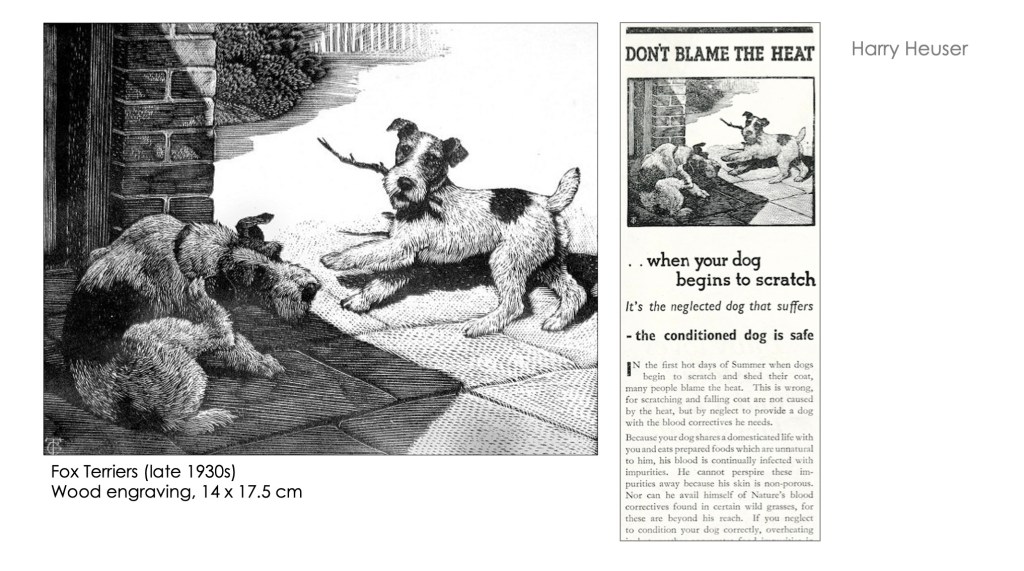

Tunnicliffe produced 18 wood engravings for Bob Martin Dog Condition Powder. They formed part of the largest marketing campaigns in the company’s history. The Archives of Bob Martin at Yatton in North Somerset is rich in detail on Tunnicliffe’s relationship with the company. It holds contracts, proofs, woodblocks and numerous examples of how the wood engravings were used in newspapers and magazines, and for shop displays and billboards.

How do you represent the work of such a diverse artist? Even if you focus on his prints, and include, as Robert Meyrick and I did, all of his known prints in an oeuvre catalogue, you miss out on the many works Tunnicliffe produced using scraperboard, which is an alternative to traditional printmaking.

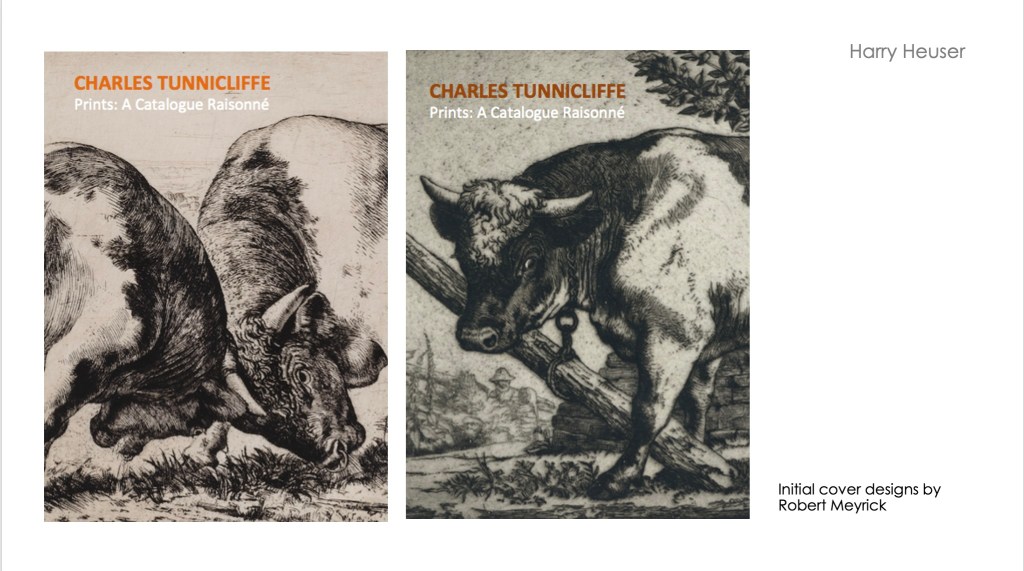

Medium aside, which subjects represent Tunnicliffe best? We thought to put his bulls on the cover, as they were what secured Tunnicliffe recognition as a fine art printmaker in the 1920s. But what about his decorative works, his farming scenes, and his book illustrations? Which animal is most Tunnicliffe? Ultimately, it was Barn Owl, one of Tunnicliffe’s last wood engravings, from 1950, that made the cover. Two subsequent wood engravings, dating from 1955 and 1956, also featured owls.

Tunnicliffe made only five wood engraving after the end of the Second World War. The strain on his eyes from working with small gravers, coupled with increasingly poor sales – 18 sales or gifts of Little Owl are listed in his Record of Sales – led Tunnicliffe to focus on the large decorative paintings for which he had found such a ready market. Tunnicliffe’s printmaking career nonetheless continued into the final decade of his life. In 1972, Tunnicliffe was persuaded to explore the potential of lithography, which are also illustrated in the catalogue.

The well-received exhibition at the RA I co-curated in 2017 was perhaps an improvement on the 1979 show, as it presented Tunnicliffe as a versatile artist and aimed at least to tell something about his extraordinary career. But it was a rather small show, and Tunnicliffe’s output deserves more space.

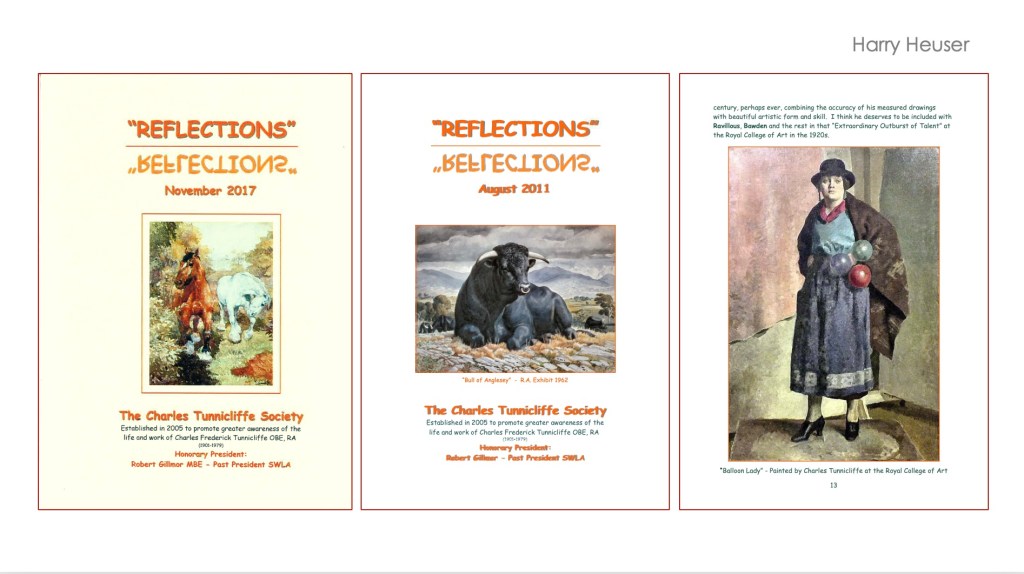

If you are interested in Tunnicliffe, I recommend you join the Tunnicliffe Society and read their journal Reflections. It tells you much more about Tunnicliffe than I could here, and it yields a great many surprising discoveries, such as the painting Balloon Seller, which returns us to the celebratory balloons at the start of this talk. It also reminds us – or, it reminds me, at least – of the responsibilities we have as writers, curators and educators not to leave everything out of the histories that does not quite fit. Things that complicate matters or muddle the clear image we like to make for ourselves of an artist.