Well, the castellan is back in his element, which is air, preferably arid. Surely it is not water. I am still drying out—coughing, sneezing, and slowly recovering—from the why-not folly of riding a rollercoaster on a rain-soaked night in Blackpool, England. Listening to the soundwaves of old broadcasts seems a comparatively safer contact with the air—and a more edifying one at that—than having one’s aged bones twirled and one’s addled brains twisted in a series of gravity-defying thrill rides.

Well, the castellan is back in his element, which is air, preferably arid. Surely it is not water. I am still drying out—coughing, sneezing, and slowly recovering—from the why-not folly of riding a rollercoaster on a rain-soaked night in Blackpool, England. Listening to the soundwaves of old broadcasts seems a comparatively safer contact with the air—and a more edifying one at that—than having one’s aged bones twirled and one’s addled brains twisted in a series of gravity-defying thrill rides.

Yet while there might have been little instruction in this bathetic experience of fairground gothics, there still was a thought to be distilled thereafter from the confines of my soused cranium. It was the thought of one who stood by in spirit that night, one taking notes while passing through a sea of everyday people; it was a passing thought of one once known as the people’s poet, America’s Carl Sandburg.

A while ago, I asked what a soundscape of Britain might turn out to be, if ever there were such an exhibition devoted to regional noise. The voicescape of the United Kingdom has been quite thoroughly mapped since then, with the BBC’s voices project capturing the diverse accents of the British Isles in hundreds of recordings now online, including a group of Blackpool Romany.

For anyone moving here with memories of Dick Van Dyke Cockney, finding everyday British voices charted like this is a revelation (even though I doubt whether my own German high school English gone Nu Yawk and Wales is represented in this mix). Carl Sandburg, who set out to render and represent the thought and speech of the American every(wo)man in the 1920s and ‘30s, might have embraced such a charting of diction—even though a map like this still calls for the voice of a poet to make it sing and signify. Sandburg attempted just that.

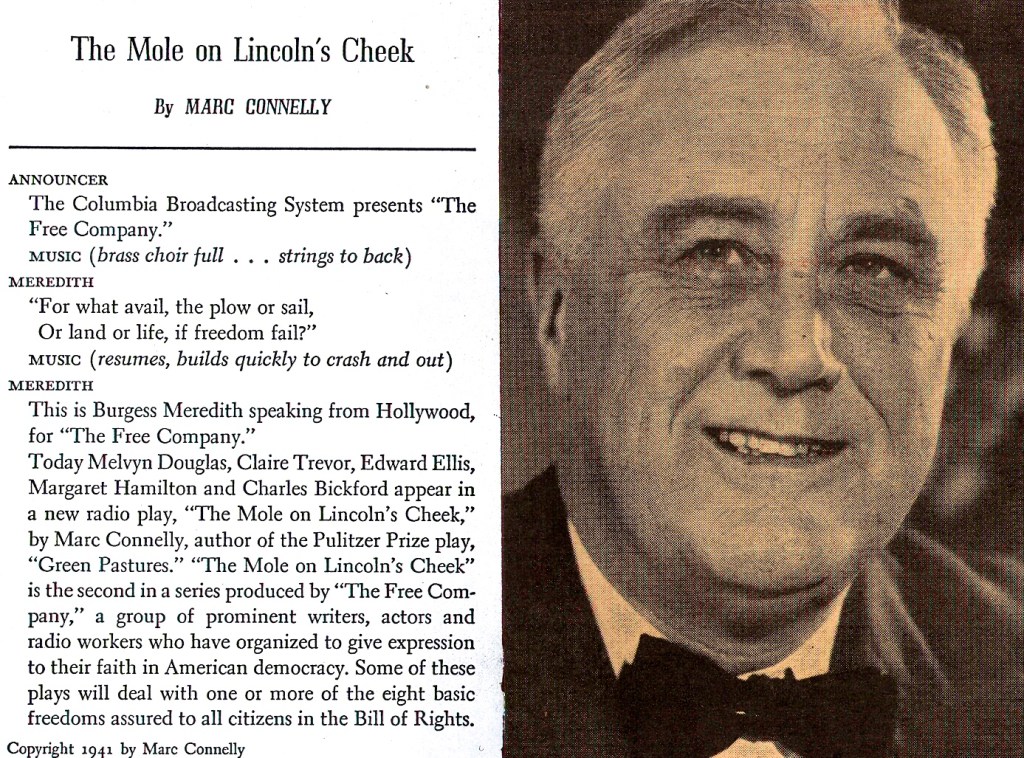

On this day in 1941, when the United States anxiously eyed a United Kingdom at war, Sandburg addressed American radio listeners on the long-running Cavalcade of America program in an effort to celebrate a unified diversity. The play, “Native Land,” opened with words read by actor Burgess Meredith, who reminded all tuning in of the timeliness of the lines to follow:

Monday, September 22, 1941. A number on a calendar, arrived at after a million years of watching the stars, of telling the time of harvest by a shadow foreshortening, and the time of planting by the sun in the equinox. September 22, 1941. We will start at the beginning; for the beginning was the land and the stars moving overhead. And that is today, this week, the land America—a beginning. And the land is what people have made of it, what people are making of it in this fourth week of September. . . .

The ensuing broadcast, which interwove excerpts of Sandburg’s verse with its author’s autobiography, expounded on the thought that a “poet must do a lot of listening before he begins to talk.”

“Where do we get these languages?” Sandburg wondered, as actor’s voiced snippets from everyday speech picked up on the streets of the poet’s home turf, Chicago. Now that the “people in cities had forgotten the old sayings,” they “talked a new lingo,” a vocal vibrancy to which the program was meant to be an anything-but-mute testimonial. The voices of the people were worth preserving, the broadcast suggested. Yet, with war in the offing, a task larger than one to be undertaken by a librarian and curator of sounds was at hand—the preservation of the people itself.

In keeping with the at times sanctimonious patriotics of the DuPont-sponsored Cavalcade program, the broadcast concluded with Sandburg’s appropriation of words from Abraham Lincoln’s Second Annual Message to Congress (1 December 1862); they were, Sandburg remarked, “Lincoln words for now, for this hour”:

The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.

In his own words compiled and adapted from his 1936 voice-collage The People, Yes, Sandburg insisted in cautious optimism that the “learning and blundering people will live on”:

This old anvil,

the people, yes,

This old anvil laughs at many broken hammers. . . .

Today, in our own “stormy present,” the internet has become the new smithy of thought. It is the workshop in which the “old anvil” is sounded anew, where people may “think anew” and speak anew, not only to suit new cases, but to revisit old. Now, I wonder whether my own language is suited to the task to revisit and reacquaint, whether I should not spent more time listening before speaking.

It sure felt comforting to hop on the rollercoaster in Blackpool, just to scream and laugh for a change. Queer and quaint, my verbiage seems ill-chosen at times to communicate my thoughts, to argue my cases old and new. . . . Still, it is my tongue, and I must have it out.

Well, the castellan is back in his element, which is air, preferably arid. Surely it is not water. I am still drying out—coughing, sneezing, and slowly recovering—from the why-not folly of riding a rollercoaster on a rain-soaked night in Blackpool, England. Listening to the soundwaves of old broadcasts seems a comparatively safer contact with the air—and a more edifying one at that—than having one’s aged bones twirled and one’s addled brains twisted in a series of gravity-defying thrill rides.

Well, the castellan is back in his element, which is air, preferably arid. Surely it is not water. I am still drying out—coughing, sneezing, and slowly recovering—from the why-not folly of riding a rollercoaster on a rain-soaked night in Blackpool, England. Listening to the soundwaves of old broadcasts seems a comparatively safer contact with the air—and a more edifying one at that—than having one’s aged bones twirled and one’s addled brains twisted in a series of gravity-defying thrill rides.