“This is Douglas Miller speaking. I’ll be very blunt and to the point. I want to give you a picture of Nazi trade methods and Nazi business methods as I saw them during my fifteen years in Berlin.” Intimate and immediate in the means and manner in which, in the days before television and internet, only network radio could reach the multitudes of the home front, the speaker addressed anybody and somebody—the statistical masses and the actual individual tuning in. The objective was to persuade the US American public that “You Can’t Do Business with Hitler.”

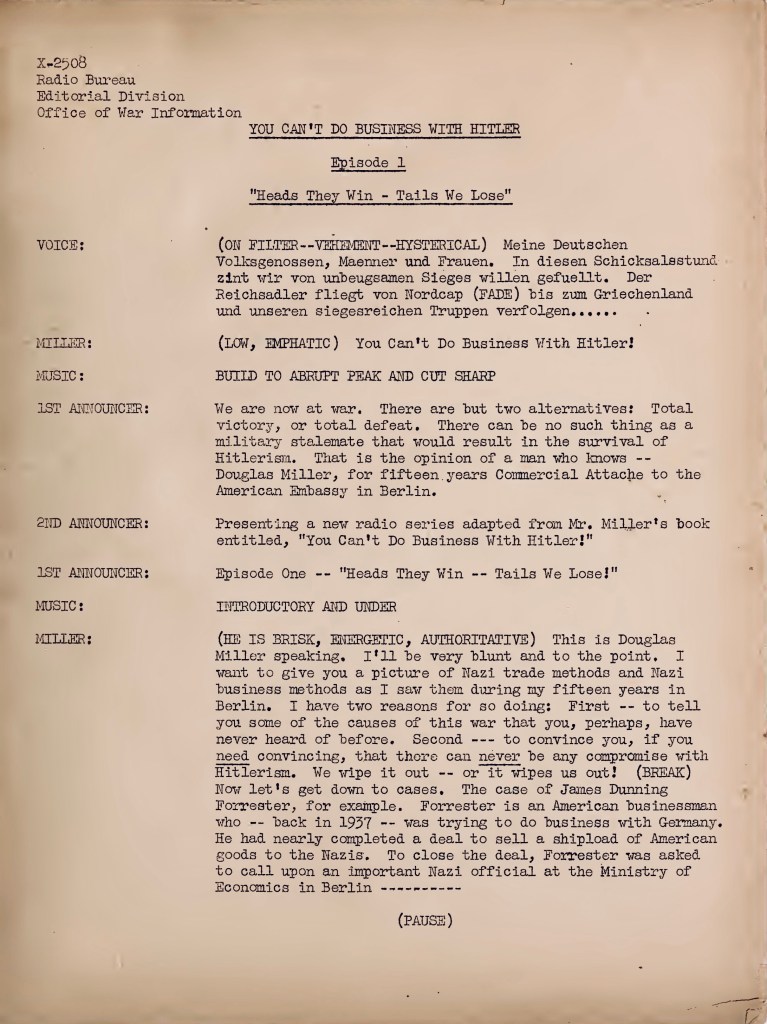

The statement served as the title of a radio program that first went on the air not long after the US entered the Second World War in the aftermath of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, an act of aggression that prompted the United States, and US radio, to abandon its isolationist stance. Overnight, the advertising medium of radio was being retooled for the purposes of propaganda, employed in ways that were not unlike the methods used in Nazi Germany.

You Can’t Do Business with Hitler was also the title of a book by Miller on which the radio series was based. Upon its publication, lengthy excerpts appeared in the July 1941 issue of The Atlantic Monthly, the editor of which introduced the article by pointing out that Miller had personally “observed German industry and particularly noted the ruthless determination with which it was directed after Hitler came to power.”

During the 1920s and ‘30s, Miller had served as Commercial Attache to the American Embassy in Berlin and had subsequently written an account of his experience. In You Can’t Do Business with Hitler, he argued that his long record of service “entitle[d]” him “to make public some of [his] experiences with the Nazis and—after drawing conclusions from them, discussing Nazi aims and methods—to project existing Nazi policy into the future and describe what sort of world we shall have to live in if Hitler wins.”

Posting this—the 855th—entry in my blog, on the day after the national election in Germany in 2025, in which the far-right, stirred by Elon Musk and JD Vance, chalked up massive gains, and in the wake of the directives and invectives with which the second Trump administration redefined US relations with many of its global trading partners—I, too, am projecting, anticipating what “sort of world” we shall find or lose ourselves if “Nazi methods” take hold in and of western democracies.

Far from retreating into the past with a twist of the proverbial dial, I am listening anew to anti-fascist US radio programs of the 1940s to reflect on the MAGA agenda in relation to the strategies of the Third Reich regime, asking myself: Can the world afford to do business with bullies?

Continue reading ““You Can’t Do Business With Hitler”: A “picture of Nazi trade methods” Re-Viewed in the Second Age of MAGA”

As of this writing, various episodes of The Shadow have been extracted some four-hundred thousand times from that vast, virtual repository of culture known, no, not as YouTube, but as the

As of this writing, various episodes of The Shadow have been extracted some four-hundred thousand times from that vast, virtual repository of culture known, no, not as YouTube, but as the

Well, this is a tough time for heroes. There might still be a need for them, but we stop short of worship. The nominal badge of honor has been applied too freely and deviously to inspire awe, let alone lasting respect. Even Superman is not looking quite so super these days, his box-office appeal being middling at best. And as much as I loathe the cheap brand of sarcasm that passes for wit these days, I am among those who are more likely to raise an eyebrow than an arm in salute.

Well, this is a tough time for heroes. There might still be a need for them, but we stop short of worship. The nominal badge of honor has been applied too freely and deviously to inspire awe, let alone lasting respect. Even Superman is not looking quite so super these days, his box-office appeal being middling at best. And as much as I loathe the cheap brand of sarcasm that passes for wit these days, I am among those who are more likely to raise an eyebrow than an arm in salute.