“Had Holmes never existed I could not have done more, though he may perhaps have stood a little in the way of the recognition of my more serious literary work.” That is how Arthur Conan Doyle, not long before his own death in 1930, announced to his readers that he would put an end to his most robust brainchild, the by now all but immortal Sherlock Holmes. Indeed, the figure continues to overshadow every aspect of Dr. Doyle’s career, literary or otherwise. Perhaps, “upstage” is a more precise way of putting it, considering that the venerable sleuth was to enjoy such success in American and British radio drama from the early 1930s to the present day.

“One likes to think that there is some fantastic limbo for the children of imagination,” Doyle assuaged those among his readers who found it difficult to accept that Holmes’s departure was merely “the way of all flesh.”

To be sure, the earlier incident at the Reichenbach Falls suggested that Holmes was impervious to threats of character assassination, that he could reappear, time and again, in the reminiscences of Doctor Watson. Still, Doyle’s intention to do away with Holmes so early in the detective’s literary career had been no mere publicity stunt. Rather than feeling obliged to supply the public with the puzzles they craved, the author felt that his “energies should not be directed too much into one channel.”

One of the lesser-known alternative channels considered by Doyle has just been reopened for inspection. Today, 22 May, on the 150th anniversary of Doyle’s birth in 1859, BBC Radio Scotland aired “Vote for Conan Doyle!” a biographical sketch “specially commissioned” to mark the occasion. In it, writer and Holmes expert Bert Coules relates how, in 1900, Doyle embarked on a career in politics. He decided to stand for parliament; but the devotees of Sherlock Holmes would not stand for it.

Coules’s play opens right where Doyle had first intended to wash his hands of Holmes—at the Reichenbach Falls. No matter how sincere Doyle was in improving the Empire’s image and the plight of the British’s troops during the Second Boer War, the push hardly met with the approval of the reading public. “How could you!” “How dare you!” “You brute!” the public protested.

Although it was not this perceived case of filicide that did him in, Doyle proved unsuccessful in his campaign—and that despite support from Dr. Bell, who served as an inspiration for Holmes. After his defeat, Doyle “bowed to the inevitable—and back the man came.”

When the The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes was published in 1927, Doyle dropped the man once more, albeit in a gentler fashion. To assuage loyal followers, he fancied Holmes and Watson in some “humble corner” of the “Valhalla” of British literature. Little did he know that the “fantastic limbo” in which the two were to linger would be that in-between realm of radio, a sphere removed from both stage and page—but nearer than either to the infinite “O” between our ears.

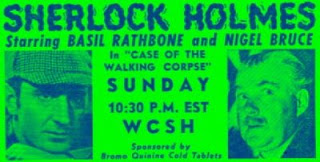

It hardly surprises that, Radio Scotland’s efforts to get out the “Vote for” and let us walk “In the Footsteps of Conan Doyle” aside, most of the programs presumably devoted to Doyle are concerned instead with “The Voice of Sherlock Holmes” and the “Game” that is “Afoot” when thespians like Cedric Hardwicke, John Gielgud, Carleton Hobbs and Clive Merrison approach the original. It is not Doyle’s life that is celebrated in these broadcasts, but Holmes’s afterlife.

True, to the aficionados of Doyle’s fiction, Sherlock Holmes has never been in need of resuscitation. Yet, as Jeffrey Richards remarked in “The Voice” (first aired in 1998),

[r]adio has always been a particularly effective medium for evoking the world of Holmes and Watson. The clatter of horses hoofs on cobbled streets, the howl of the wind on lonely moors, and the sinister creaks and groans of ancient manor houses steeped in history and crime.

The game may be afoot once more when Holmes returns to the screen this year; but, outside the pages that could never quite contain him, it is the “fantastic limbo” of radio that kept the Reichenbach Falls survivor afloat. It is for the aural medium—the Scotland yardstick for fidelity in literary adaptation—that all of his cases have been dramatized and that, in splendid pastiches like “The Abergavenny Murder,” the figure of Sherlock Holmes has remained within earshot all these years.

Related writings

“‘What monstrous place is this?’: Hardy, Holmes, and the Secrets of Stonehenge”

“Radio Rambles: Cornwall, Marconi, and the ‘Devil’s Foot’”

Old Sleuth Re-emerges in New Medium for American Ho(l)mes

Well, I am not sure which state of oblivion is more tolerable: to forget or to be forgotten. I tend to commute between the two, as most folks do. Yet I am far more troubled by the defects of my own memory than by any failure on my part to leave an indelible imprint of me on the minds of others. The latter might injure my pride from time to time; but the former damages the very core of my self as a being in space and time. Is this why I am attracted to pop-cultural ephemera, to the once famous and half forgotten, to the fading sounds of radio and the passing fame of its personalities? Am I, by trying to keep up with the out-of-date, rehearsing my own struggle of keeping anything in mind and preventing it from fading?

Well, I am not sure which state of oblivion is more tolerable: to forget or to be forgotten. I tend to commute between the two, as most folks do. Yet I am far more troubled by the defects of my own memory than by any failure on my part to leave an indelible imprint of me on the minds of others. The latter might injure my pride from time to time; but the former damages the very core of my self as a being in space and time. Is this why I am attracted to pop-cultural ephemera, to the once famous and half forgotten, to the fading sounds of radio and the passing fame of its personalities? Am I, by trying to keep up with the out-of-date, rehearsing my own struggle of keeping anything in mind and preventing it from fading?