Well, it was a scorcher of a day—the first I experienced here in temperate Wales. The unexpected heat brings back memories of my many summers in New York City and will prepare me for my return to the asphalt jungle this August. Moving to rural Wales from that bustling metropolis took more of an adjustment than adding a few layers of clothing; but anyone ready to weave life according to E. M. Forster’s motto “Only connect,” which is not a bad motto to live by, there is the comfort of that web of relations that, however remote or isolated you might believe yourself to be, will place you smack in the middle of the world, like a spider resting in the assurance that flies are bound to drop in, by and by.

Here is one such moment in the web in which I find myself. You might have to stretch your antennae a bit to get caught up in it.

Picture this: New York City, on this day, 18 July, in 1936. It’s the premiere of The Columbia Workshop, the most experimental and innovative of all the radio dramatic series produced during the so-called “golden age” of old-time radio. For that first broadcast, the Workshop revived what is generally considered to be the first original play for radio: The Comedy of Danger, by British playwright-novelist Richard Hughes, better known for A High Wind in Jamaica (1929), an adventure story that has been ranked among the hundred best novels of the twentieth century.

Danger is a sort of Poseidon Adventure staged in utter darkness; a spectacular melodrama of disaster involving three people about to drown in a collapsed coal mine. It is a scenario mined for the theater of the mind, evoked by sounds and silence alone. Danger was first produced by the BBC on 15 January 1924, but was still a novelty act when the Workshop chose it for its inaugural broadcast more than twelve years later. Back in 1924, US radio had no use for such theatricals, Hughes remarked in an article about “The Birth of Radio Drama”:

A few months [after the BBC production], finding myself in New York, I tried to interest American radio authorities in the newborn child. Their response is curious when you consider how very popular radio plays were later to become in the States. They stood me good luncheons; they listened politely; but then they rejected the whole idea. That sort of thing might be possible in England, they explained, where broadcasting was a monopoly and a few crackpot highbrows in the racket could impose what they liked on a suffering public. But the American setup was different: it was competitive, so it had to be popular, and it stood to reason that plays you couldn’t see could never be popular. Yet it was not very long before these specially written “blind” plays (my own “Comedy of Danger” among them) began to be heard in America, and on the European continent as well.

Other than creating a situation in which the characters are as much bereft of sight as the audience, Danger has no artistic merit. It purports to be philosophical about death; but the fifteen minutes allotted for this piece of melodramatic hokum are hardly time enough to probe deeply, and much of the dialogue is ho-hum or altogether laughable.

What makes this seemingly generic if radiogenic play more personally meaningful to me is that it was written by a Brit of Welsh parentage, by a man who chose to live in a Welsh castle, and who chose, for this, his first dramatic piece for radio, a story set not far from the very hills where I found myself after these long years of writing in New York City about American radio drama. Is it a coincidence that I came home to the birthplace of radio drama?

“Goodness knows!” exclaims one of the trapped visitors,

I’d expect anything of a country likes Wales! They’ve got a climate like the flood and a language like the Tower of Babel, and then they go and lure us into the bowels of the earth and turn the lights off! Wretched, incompetent—their houses are full of cockroaches—Ugh!

In the background, Welsh miners face their fears by singing “Aberystwyth”—the name of the town near which I now reside. The Welsh, of course, are known for their oral tradition, for their singing and poetry recitals; their most famous poet is Dylan Thomas, author of the best know of all radio plays, “Under Milkwood.” It is here that American radio drama is still being thought of and written about: Rundfunk und Hörspiel in den USA 1930-1950 (1992), for instance, by fellow German Eckhard Breitinger, was written here, as was Terror on the Air, by Richard J. Hand, published in 2006. It is here, in Wales, that I started communicating with radio dramatist Norman Corwin; and it is here that, after a short break from my journal, I will continue my visits to the theater of the mind.

Yes, it is a web all right, even though I am not sure whether it was woven by or for me. I am merely discovering connections that, upon reflection, are plain to see and comforting to behold.

Well, it is supposed to be busting out all over tomorrow. June, that is—the month during which television entertainment goes bust. In the US, at least, a generally enforced leave-taking from your favorites is a programming pattern that predates television. Looking through my radio files, I came across an article in the June 1932 issue of The Forum, discussing what Americans could expect to find “On the Summer Air.” It is an interesting piece, especially since it serves as a reminder that, during the early years of broadcasting, the summer hiatus was a response to technical difficulties. The shutting down of broadcast studios, like the closing of Broadway theaters, was directly related to the rising mercury, to the heat that made the asphalt buckle and urbanites escape to their vernal retreats.

Well, it is supposed to be busting out all over tomorrow. June, that is—the month during which television entertainment goes bust. In the US, at least, a generally enforced leave-taking from your favorites is a programming pattern that predates television. Looking through my radio files, I came across an article in the June 1932 issue of The Forum, discussing what Americans could expect to find “On the Summer Air.” It is an interesting piece, especially since it serves as a reminder that, during the early years of broadcasting, the summer hiatus was a response to technical difficulties. The shutting down of broadcast studios, like the closing of Broadway theaters, was directly related to the rising mercury, to the heat that made the asphalt buckle and urbanites escape to their vernal retreats.

Government radio is a cross between a museum and a religious school, dispensing classics and credo, but not especially concerned with new works. Commercial radio is a department store, carrying in stock a few luxury items, a lot of supposedly essential commodities and perhaps too many cheap brands of goods. The radio [as imagined and desired by some who write for the medium] is an artist’s studio, dedicated to creation alone. As such, it is not yet able to stand on its own, and its product must be exhibited in the museum or the gallery of the department store.

Government radio is a cross between a museum and a religious school, dispensing classics and credo, but not especially concerned with new works. Commercial radio is a department store, carrying in stock a few luxury items, a lot of supposedly essential commodities and perhaps too many cheap brands of goods. The radio [as imagined and desired by some who write for the medium] is an artist’s studio, dedicated to creation alone. As such, it is not yet able to stand on its own, and its product must be exhibited in the museum or the gallery of the department store. Moving to the UK from the movie junkie heaven that is New York City meant having to find new ways of getting my cinematic fix. Gone are the nights of pre-code delights at the

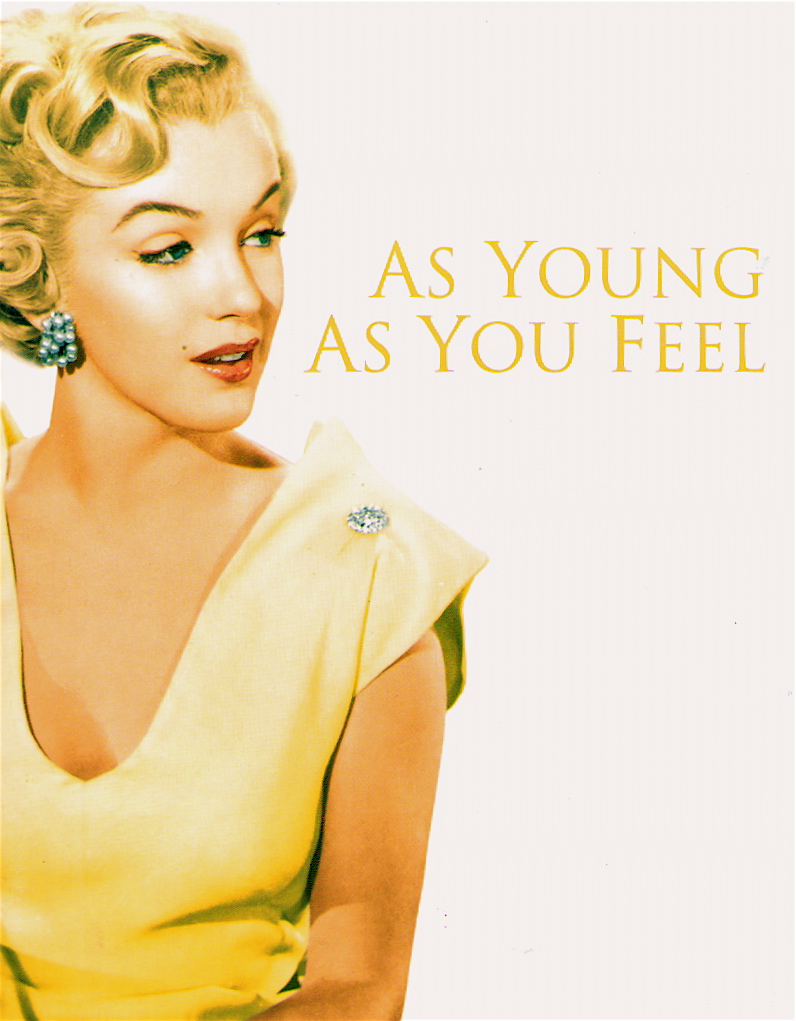

Moving to the UK from the movie junkie heaven that is New York City meant having to find new ways of getting my cinematic fix. Gone are the nights of pre-code delights at the