“You will want to know what are my qualifications,” Ring Lardner introduced himself to the readers of his new radio column in the New Yorker back in June 1932. “Well,” the renowned humorist-turned-broadcast critic remarked, “for the last two months I have been a faithful listen-inner, leaving the thing run day and night [ . . .].” Lardner was hospitalized at the time, but he sure knew how to make the most of his misfortune by twisting the dial long enough to squeeze a few bucks out of it, and that at a time when, like today, there were hardly any competitors on the scene but, unlike today, there were millions eager to listen to and read about the radio, its programs and personalities.

“You will want to know what are my qualifications,” Ring Lardner introduced himself to the readers of his new radio column in the New Yorker back in June 1932. “Well,” the renowned humorist-turned-broadcast critic remarked, “for the last two months I have been a faithful listen-inner, leaving the thing run day and night [ . . .].” Lardner was hospitalized at the time, but he sure knew how to make the most of his misfortune by twisting the dial long enough to squeeze a few bucks out of it, and that at a time when, like today, there were hardly any competitors on the scene but, unlike today, there were millions eager to listen to and read about the radio, its programs and personalities.

Believe me, there is nothing like a sickbed to turn you on to radio and into an avid listener, especially when all you want to do is close your eyes and have stories told to you. No other qualifications are needed to become a critic of the medium. No wirelessons required, if I may be Walter Winchell about it.

Sometimes, though, listening does not seem to be an option. Hundreds of the programs available to Lardner back then are no longer extant; earlier programs are still more difficult to uncover. This is particularly frustrating when you have heard of a show without ever getting a chance to hear it. One such forgotten program is Real Folks, the first dramatic series to air on NBC’s Blue network. It premiered on 6 August 1928 and ran for the relatively short period of three years.

Years ago, I came across a brief description of the series in Radio Writing (1931), a contemporary book on broadcast drama penned by radio dramatist Peter Dixon, who recommended Real Folks for being “excellent characterization and an example of the attractiveness of simple, homely humor.” As a radio critic, you do not want to take anyone’s word for the “it” of listening. Was I ever going to hear for myself?

Recovering from a seemingly interminable cold, I am fortunate in having much time to go in search of lost voices. You might say that I excite easily, but today I was thrilled to meet those Real Folks for the first time. On this day, 17 November, in 1940, writer George Frame Brown was joined by members of the original cast to bring back the series for a special broadcast. By then, the pioneering drama had been off the air for nearly a decade.

After a short and not altogether factual introduction by announcer Graham McNamee, the Real Folks sketch heard on Behind the Mike opens with a train whistle, a sound that, like no other, is capable of transporting you swiftly into town and country—and to any Whistle Stop along the tracks. Thompkins Corner was one of those places. Its mayor was Matt Thompkins, who was also the owner of the town’s general store. He was played by the man who knew him best: George Frame Brown.

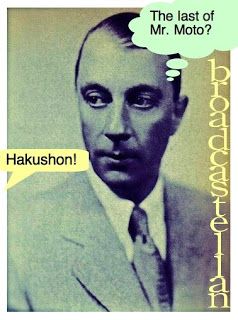

Apart from its writer, the cast of Real Folks included Irene Hubbard, Ed Whitney, and Elsie Mae Gordon (pictured), all of whom were reunited for the Behind the Mike broadcast which, in its sentiment and politics, returned 1940s listeners straight back to the Depression, with a story involving lost jewelry, a stolen banana, and a destitute yokel. The sketch concludes with the sounds of the whip-poor-will and the Capraesque words of the Mayor who, having faced and avoided the end of his career, pensively remarks:

I guess there’s a lot of folks way up in politics tonight that wishes they was back living beside the country road listening to a whip-poor-will.

Perhaps, that rarely seen yet distinctive sounding bird was a metaphor for the radio, the preferred medium of the not-so-way up who enjoyed to find themselves represented by “home folks” like Vic and Sade, Lum and Abner of Pine Ridge, and Real Folks like those in Thompkins Corner; and it was voice talents like Elsie Mae Gordon who made it all sound authentic.

During the original run of Real Folks, Theatre Magazine‘s Howard Rockey pointed out Elsie Mae Gordon as a “veteran trouper” who came to radio “from the concert and vaudeville stages.” A sought-after player in those early days of radio drama, Gordon took on as many as

six to eight separate roles in the course of a single broadcast. To each of these “doubles” she imparts a distinct individuality, so natural that it is difficult to believe oneself listening to a “one-girl show.” In some sketches her lines are from her own pen, so that the complete interpretation is of her own devising. Miss Gordon’s differing voices are familiar to all who tune in on Real Folks, the Kukus, Detective Story thrillers and other weekly features.

Some of that versatility is also apparent in the Behind the Mike broadcast, the gender-bent casting being disclosed at the conclusion of the sketch. At the time of her reunion with her Real Folks co-stars, Gordon was still active in radio, notably in the distinguished anthology Columbia Workshop.

Her portrayal as Matt Thompkins’s wife, however, would have fallen out of earshot had it not been for the producers of Behind the Mike, who, as early as 1940, promoted the medium by featuring voices we would otherwise only read about. Indeed, Behind the Mike brought back Gordon a few weeks later to talk about her role as a voice coach.

Without voices like Gordon’s, and without all the real folks who make them heard on the web, I would have very little to go on about in this journal … except, perhaps, that my own voice has all but vanished as a result of the cold that has me listening, somewhat enviously, to the speech sounds of a bygone era.