Nowadays, the concept of not having a voice is so alien to most of us Westerners that we fool ourselves into believing that what we are saying is of consequence, that because words are sent into the world they may also change it. We are too used by now to telecommune via phone or internet that the one-sidedness of broadcasting strikes us as downright barbaric. Why listen and be still when we can chatter and twitter, why take in a thought when we can put out a great deal of thoughtlessness with the greatest of ease? Publishing online or opining about world events on our slick mobiles, we are apt to believe that we have the world at our lips and by the ear. We are given gadgets—or, rather, we purchase them at considerable cost—that encourage us to exhaust ourselves in gossip while permitting others to check that our talk is indeed idle.

The talking disease is the talking cure of our modern society: the comforting illusion of having the power to say anything, anytime serves a system that, if our words mattered, would have to resort to more drastic acts of silencing.

Back in early 1930s Germany, Bertolt Brecht rejected radio as a distribution apparatus, a machine through which the few addressed the many, generally in the guise of speaking on their behalf. The German for broadcasting itself is misleading. “Rundfunk” (literally, sparking around) hardly captures the one-sidedness of transmission. Brecht was looking forward to the day in which broadcasting could be a system of exchange, the kind of wireless telephony now available to us, at least technologically speaking.

Instead, German radio cut off all means of response other than compliance. It removed from the dial any voices that might utter second opinions. Effectively, it removed the dial itself by tuning the public to the official channel, and to that channel alone. Today, 18 August, the Volksempfänger turns 75. It was not simply the furniture of fascism. It was its furnisher.

The Volksempfänger (the people’s receiver) fed Germans with whatever was in the interest of the Reich, that is, the governing body rather than anybody being thus governed. This privilege of being talked down to, of being shouted at and being shouted down, was offered at a discount—a discount that ended dissent in the bargain. Dictatorships, after all, depend on dictation.

Brecht had reason to be wary of broadcasting, a means of listening that precluded response. Does not the German language suggest that the German people are prone to being led by the ear? The German for “hearing” is “hören,” a related form of which is “horchen.” Both are the root of a great many words, and some weighty ones at that.

Take “gehören,” for instance, which means to belong, while “verhören” means to interrogate. “Hörig sein,” in turn, means “to be submissive,” and “gehorchen” means to obey. “Auf jemanden hören” means to pay heed. Remove the “jemand” (the anybody), and you have “aufhören,” which means to end, as free speech did when the Volksempfänger became cheaply available to anybody.

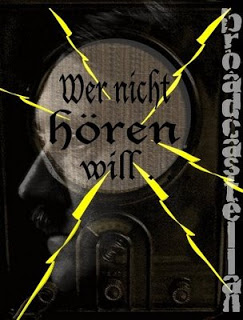

Today, we have the opportunity to receive as well as broadcast. We can take in hundreds of channels and put out millions of words. It calms many of us to the point of not speaking up. We can, therefore we don’t. A system that does not take the microphone away from us, that permits us to air our concerns, must be fair system. Why listen to anyone who tells us otherwise? Well, “Wer nicht hören will muss fühlen,” a German saying goes. Its meaning? Those who don’t listen shall feel the consequences.

Well, it rolled into town last night . . . and carted me right back to high school (in Germany, anno never-mind), where I was exposed to it first. The National Theatre’s “education mobile,” I mean, whose production of Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle I went to see at the local

Well, it rolled into town last night . . . and carted me right back to high school (in Germany, anno never-mind), where I was exposed to it first. The National Theatre’s “education mobile,” I mean, whose production of Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle I went to see at the local