Radio has always promoted other media, despite the competition it faced from print and screen. To some degree, this led to its decline as a dramatic medium. Producers made eyes at the pictures, neglecting to develop techniques that would ensure radio’s future as a viable alternative to visual storytelling. Television had been around the corner virtually from the beginnings of broadcasting; even in the 1920s, radio insiders were expecting its advent. So, the old wireless was often seen as little more than a placeholder for television, an interim tool for advertisers eagerly awaiting the day on which they no longer had to spell out what they could show to the crowd.

One of the last big hurrahs of radio during the early 1950s was The Big Show, a variety program hosted by actress Tallulah Bankhead (last revisited here). Sure, Bankhead promoted the movies—but on this day, 29 April, in 1951, she doubtlessly had something else in mind when she expressed herself “privileged to hear a portion of a truly great new Warner Bros. picture, starring Frank Lovejoy.”

According to Joel Lobenthal’s biography of the actress, Bankhead had a “phobia about communism,” largely owing to her Catholic upbringing. Yet, as George Baxt, a theatrical agent involved in booking talent for the program, tells it in The Tallulah Bankhead Murder Case, a mystery set during those Big Show nights, her show struggled as a result of this anxiety and the forms it took.

Not Bankhead’s anxieties—the measures taken by fierce anti-Communists to blacklist (or at least graylist) allegedly subversive players. By the early 1950s, even comedienne Judy Holliday was considered suspicious, which did not stop Bankhead from welcoming her on the Big Show on several occasions.

By playing a scene from a soon-to-be-released spy thriller titled I Was a Communist for the FBI, Bankhead fought for the life of the Big Show, now that even she, the fierce anti-Communist, had come under attack. As Bankhead pointed out, I Was a Communist was a dramatization of the Saturday Evening Post stories based on experience of counterspy Matt Cvetic, whom Lovejoy “deem[ed] it an honor” to portray.

“It certainly brought home to me the patriotic devotion and the sheer guts that Matt needed to take that nine-year beating.” At this point, a voice is heard, off-mike, telling Lovejoy that “someone had to do it.” That someone, speaking to the listening audience, was none other than Matt Cvetic:

Well, Frank, maybe we’d better wait until the job is done before we start taking bows. The job is far from finished. We’re just beginning to fight back against the deadly, ruthless, highly organized Soviet-controlled conspiracy. So, we’ve got a lot of fighting yet to do before we can rid ourselves of this greatest threat to the world of free men. We’ve got to fight. All of us. All the time.

“Amen to that,” Bankhead responded enthusiastically as the crowd in the studio applauded. Threatened by the blacklisters and the menace of television, Ms. Bankhead knew she had to fight—for the good of the country and the good of her show. The Big Show went off the air a year later, just as the aforementioned radio version of I Was a Communist began its syndicated run . . .

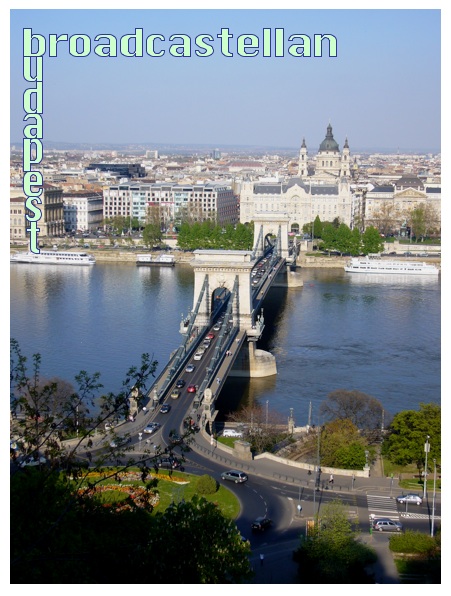

According to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, our “universal language” is music. This might account for the international crowd at Budapest’s splendid opera and operetta houses; or perhaps it is ticket prices, which the locals are less likely to tolerate than the visitors in town for a good time. It is like that the world over, I suspect. New Yorkers are hardly the main audience for Broadway shows. What is on offer in any cultural center is largely owing to centrifugal forces. Is it the music that is universally understood? Or is it just that money talks without an accent?

According to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, our “universal language” is music. This might account for the international crowd at Budapest’s splendid opera and operetta houses; or perhaps it is ticket prices, which the locals are less likely to tolerate than the visitors in town for a good time. It is like that the world over, I suspect. New Yorkers are hardly the main audience for Broadway shows. What is on offer in any cultural center is largely owing to centrifugal forces. Is it the music that is universally understood? Or is it just that money talks without an accent?

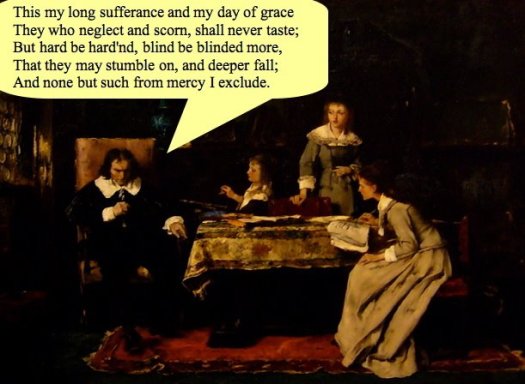

I appreciate a good hoax; and no hoax is any good unless it wrings from you the admission that you have been had. My common sense yields to the artistry of the con, the handiwork of cheeky tricksters who can cheat you out of your trousers by presenting you a with a hook from which to suspend your disbelief. And however desperately I might try to cover up and recover my composure by juggling an assortment of polysyllables, I am just the kind of fall guy you’d love to be around on April Fools’ Day—or any other day, if you are among those who practice their legerdemain without a license.

I appreciate a good hoax; and no hoax is any good unless it wrings from you the admission that you have been had. My common sense yields to the artistry of the con, the handiwork of cheeky tricksters who can cheat you out of your trousers by presenting you a with a hook from which to suspend your disbelief. And however desperately I might try to cover up and recover my composure by juggling an assortment of polysyllables, I am just the kind of fall guy you’d love to be around on April Fools’ Day—or any other day, if you are among those who practice their legerdemain without a license. No matter how hard I tried to make light of them, by pulling their fingers or sitting on their boots, the colossal statues gathered in the ideological leper colony that is

No matter how hard I tried to make light of them, by pulling their fingers or sitting on their boots, the colossal statues gathered in the ideological leper colony that is  Well, that didn’t last long, did it? The wireless connection in our hotel room in Budapest, I mean. It pretty much collapsed after about 48 hours, even though we had paid a small bundle to be online for the week. Not that I find it easy to keep this journal, to keep up with the out-of-date while being out and about on my travels. Our days were filled with taking in the sights; our evenings (and bellies) with goulash, goose liver, and Hungarian wines—from which culinary excesses arose the most curious and vivid dreams. I was paying my respects at the bedside of the

Well, that didn’t last long, did it? The wireless connection in our hotel room in Budapest, I mean. It pretty much collapsed after about 48 hours, even though we had paid a small bundle to be online for the week. Not that I find it easy to keep this journal, to keep up with the out-of-date while being out and about on my travels. Our days were filled with taking in the sights; our evenings (and bellies) with goulash, goose liver, and Hungarian wines—from which culinary excesses arose the most curious and vivid dreams. I was paying my respects at the bedside of the