The Darwin bicentenary is drawing to a close. Throughout the year, exhibitions were staged all over Britain to commemorate the achievements of the scientist and the controversy his theories wrought; numerous plays and documentaries were presented on stage, screen and radio, including a new production of Inherit the Wind (1955), currently on at the Old Vic. I was hoping to catch up with it when next I am in London; but, just like last month, I my hopes went the way of all dodos as only those survive the box office onslaught who see it fit to book early.

Not that setting foot on the stage of the Darwin debate requires any great effort or investment once you are in the great metropolis. During my last visit to the kingdom’s capital, I found myself—that is to say, I was caught unawares as I walked through the halls of the Royal Academy of Arts—in the very spot where, back in 1858, the papers that evolved into The Origin of Species were first presented.

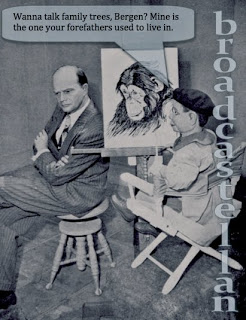

This week, BBC Radio 4 is transporting us back to a rather less dignified scene down in Dayton, Tennessee, where, in the summer of 1925, the theory of evolution was being put on trial, with Clarence Darrow taking the floor for the defense. Peter Goodchild, a writer-producer who served as researcher for and became editor of the British television series on which the American broadcast institution Nova was modeled, adapted court transcripts to recreate the media event billed, somewhat prematurely, as the “trial of the century.”

Like the LA Theatre Works production before it, this new Radio Wales/Cymru presentation boasts a pedigree cast including tyro octogenarians Jerry Hardin as Judge John Raulston and Ed Asner as William Jennings Bryan, John de Lancie as Clarence Darrow, Stacy Keach as Dudley Field Malone, and Neil Patrick Harris as young biology teacher John Scopes, the knowing if rather naive lawbreaker at the nominal center of the proceedings who gets to tell us about it all.

“I was enjoying myself,” the defendant nostalgically recalls his life and times, anno 1925, as he ushers us into the courtroom, for the ensuing drama in which he was little more than a supporting player. “It was the year of the Charleston,” of Louis Armstrong’s first recordings, “the year The Great Gatsby was written.” Not that marching backwards to the so-called “Monkey trial” is—or should ever become—the stuff of wistful reminiscences. “But, in the same year, Hitler wrote Mein Kampf, Scopes adds, “and in Tennessee, they passed the Butler Act.”

Darrow called the ban on evolution as a high school subject—and any subsequent criminalization of intellectual discourse and expressed beliefs—the “setting of man against man and creed against creed” that, if unchallenged, would go on “until with flying banners and beating drums, we are marching backwards to the 16th century.”

He was not, of course, referring to the Renaissance; rather, he was dreading a rebirth of the age of witch-hunts, superstitions and religious persecution. “We have the purpose of preventing bigots and ignoramuses from controlling the education of the United States, and you know it, and that is all,” Darrow declared.

It is a line you won’t hear in the play; yet, however condensed it might be, the radio dramatization is as close as we get nowadays to the experience of listening to the trial back in 1925, when it was remote broadcast over WGN, Chicago, at the considerable cost of $1000 per day for wire charges. According to Slate and Cook’s It Sounds Impossible, the courtroom was “rearranged to accommodate the microphones,” which only heightened the theatricality of the event.

I have never thought of radio drama as ersatz; in this case, certainly, getting an earful of the Darrow-Bryan exchange does not sound like a booby prize for having missed out on the staging and fictionalization of the trial as Inherit the Wind.

Related post

“Inherit the . . . Air: Dialing for Darwin on His 200th Birthday”

Before settling down for a small-screening of Inherit the Wind, I twisted the dial in search of the man from whose contemporaries we inherited the debate it depicts: Charles Darwin, born, like Abraham Lincoln, on this day, 12 February 1809. Like Lincoln, Darwin was a liberator among folks who resisted free thinking, a man whose ideas not only broadened minds but roused the ire of the close-minded–stick in the muds who resented being traced to the mud primordial, dreaded having what they conceived of as being set in stone washed away in the flux of evolution, and resolved instead to keep humanity from evolving. On BBC radio, at least, Darwin is the man of the hour. His youthful

Before settling down for a small-screening of Inherit the Wind, I twisted the dial in search of the man from whose contemporaries we inherited the debate it depicts: Charles Darwin, born, like Abraham Lincoln, on this day, 12 February 1809. Like Lincoln, Darwin was a liberator among folks who resisted free thinking, a man whose ideas not only broadened minds but roused the ire of the close-minded–stick in the muds who resented being traced to the mud primordial, dreaded having what they conceived of as being set in stone washed away in the flux of evolution, and resolved instead to keep humanity from evolving. On BBC radio, at least, Darwin is the man of the hour. His youthful