My memory is poor, generally, and getting worse. My desire to remember the forgotten – the ostensibly unmemorable – remains strong. It is a love rooted in the need to champion the unloved, or, rather, the dis-loved, and to abandon myself to the abandoned. It is a queer thing, to my thinking, which is queer always and could not be otherwise. To love, perversely, what has been discarded or deemed unworthy of consideration, means disregarding what is widely held to matter and instead be drawn – draw on and draw out – what is devalued as immaterial. It involves questioning systems of valuation and creating oppositional values.

Commenced in 2005, this journal was dedicated to what I termed “unpopular culture,” the uncollected leftovers that linger on a trash heap beyond our mythical collective memory. To this day, down to my current project, Asphalt Expressionism – a curated collection of images engaging with the visual culture of New York City sidewalks – I carry on caring about the uncared-for and neglected, the everyday past which others tend to walk without taking notice.

There is no such thing as trivial matter. Nothing is negligible in itself. What makes something worthless is not a particular quality or lack thereof. Rather, it is an attitude, an approach, a judgment – itself often a product of a cultural conditioning. Nothing is intrinsically trivial, but anything may be trivialized. As I put it, years ago, when I curated (Im)memorabilia, an exhibition largely of mass-produced prints entirely from my collection – “Trivia is knowledge we refuse the potential to matter,” whereas “Memorabilia is matter we grant the capacity to mean differently.”

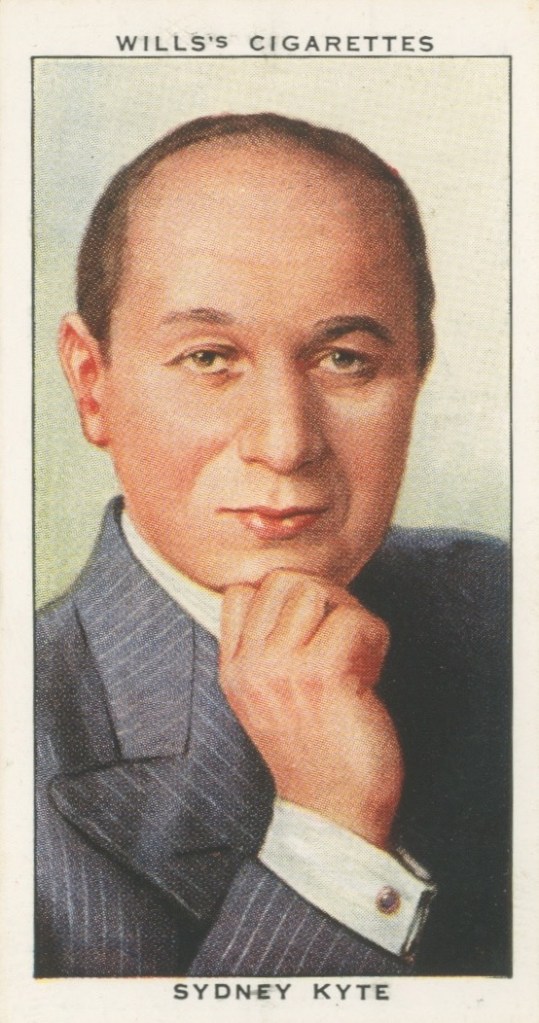

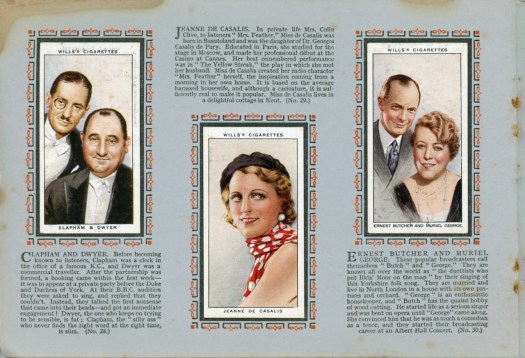

A 1930s cigarette card, for instance, may have once served the purpose of boosting sales by prompting smokers to collect cheaply mass-produced images of film stars or flowers or tropical fish. Collecting them nearly a century later – long after the advertising campaign has folded and the image has become removed from the product it was designed to promote – means to extend the lives of such devalued objects by moving them into the sphere of our own temporary existence of which they in turn become extensions.

Whether or not we take measures to preserve their afterlife, we instill collectibles with new meaning, give them value by investing them with our longings. I, for one, never regard my belongings as financial investments; I do not collect calculatedly, anticipating that what I gather might be the worth something to someone else some day.

I also refuse to intellectualize my desires; I am wary of turning passion into an academic exercise. That is, I do not rescue the marginalized for the purpose of demarginalizing my own existence by convincing others of the cultural value or historical significance of devalued objects – and of the case I make for their value. Still, there is that longing to be loved, to feel validated, for all the reasons that many, I suspect, would regard as wrong.

Why waste time on what is waste? Why dig up – and dig – what has become infra-dig through the process of devaluing, a hostile attitude toward the multiple, the unoriginal and commercially tainted to which we appear to be conditioned in a capitalist system that makes us feel lesser for consuming the mass-produced within our means so that we aim to live beyond those means, always abandoning one product for another supposedly superior? There can be no upgrading without degradation, no aspiration without a looking down at what has been relegated to refuse.

I remember a gay friend telling me, decades ago, that when he was a child, drawing in kindergarten or elementary with other children, he would pick the color that was least liked by his fellow creatives. I did the same thing when toys were being shared. This unwanted thing could be me – this is me – is what must have gone through my mind when I took temporary ownership of the object of just about nobody’s affection. And this, I believe, is at the heart of my impulse to make keepsakes of the largely forsaken.

I started writing this on the one-hundredth anniversary of the first radio broadcast in Britain – 14 November 1922 – by what was then not yet the BBC. Sound, after all, is the ultimate ephemera, fleeting if uncollected, lost if not cared for. The BBC used to erase recordings of its broadcasts, turning the potentially memorable into the immemorabilia beyond my grasp, and, in turn, turning my determination to lift them into my presence into futile longing, a nostalgia for the unrecoverable past.

Well, howdy. His handsome mug is before me whenever I grab a book from my shelves. Randolph Scott, Series two, Number 385 of Zuban’s

Well, howdy. His handsome mug is before me whenever I grab a book from my shelves. Randolph Scott, Series two, Number 385 of Zuban’s