“Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. The Lady Astor Screen Guild Players have a surprise for you tonight.” Such a promise may well have sounded hollow to many of those tuning in to the Guild program broadcast on this day, 27 March, back in 1944. That it was grandiloquently voiced by the avuncular-verging-on-the-oleaginous Truman Bradley, whom American radio listeners knew as a voice of commerce, hardly imbued such a potential ruse with sincerity. And yet, the program is indeed a surprise, and a welcome one at that. The broadcast is a rarity in scripted radio comedy: one of those occasions when ham is not only sliced generously but consumed with gusto. Granted, I may be somewhat of a hypergelast, the kind of fellow Victorian poet-novelist George Meredith denounced as a fool who laughs excessively. Still, believe me when I say in a voice that has nothing to advertise but its own taste, poor or otherwise: this is one is a riot.

“Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. The Lady Astor Screen Guild Players have a surprise for you tonight.” Such a promise may well have sounded hollow to many of those tuning in to the Guild program broadcast on this day, 27 March, back in 1944. That it was grandiloquently voiced by the avuncular-verging-on-the-oleaginous Truman Bradley, whom American radio listeners knew as a voice of commerce, hardly imbued such a potential ruse with sincerity. And yet, the program is indeed a surprise, and a welcome one at that. The broadcast is a rarity in scripted radio comedy: one of those occasions when ham is not only sliced generously but consumed with gusto. Granted, I may be somewhat of a hypergelast, the kind of fellow Victorian poet-novelist George Meredith denounced as a fool who laughs excessively. Still, believe me when I say in a voice that has nothing to advertise but its own taste, poor or otherwise: this is one is a riot.

Affable character actor Jean Hersholt, then President of the Motion Picture Relief Fund and star of his own sentimental radio series (Doctor Christian), takes over from the announcer to introduce the players for the evening. You can buy a line from a man like Hersholt. His is a thick, honest-to-goodness accent that sounds trustworthy compared to whatever slips from the trained tongues of promotion.

Tonight, he tells us, “we have Barbara Stanwyck, Basil Rathbone, and director Michael Curtiz, three of filmdom’s outstanding personalities who will offer. . . .” At this moment, Hersholt is cut short by the one who generally occupies that spot, the man entrusted with the dearly paid-for delivery of cheap assurances.

“Uh, just a minute, Jean,” Bradley interjects, “I thought that Jack Benny was supposed to be one of the guests here tonight.” This exchange sets up the slight comedy known as “Ham for Sale,” a fine vehicle for Jack Benny, the master of comic deflation, the jokester known for his largely unfulfilled aspirations as a thespian and classical musician.

According to Hersholt, Benny got “a little temperamental”; so he will not be heard on the program. Hersholt’s recollections give way to a dramatized account of Benny’s response to the proposed broadcast. “I haven’t got anything against you, Jack. But you’re a comedian; and, frankly, I don’t think you have enough dramatic ability to play the lead opposite Miss Stanwyck.” Upon which the slighted comedian sets out to win the part.

The hilarity generated by “Ham for Sale” is not so much scripted than delivered. Greatly responsible for the kicks you’ll get out of this broadcast is the highly regarded, Oscar-winning director of Casablanca, whose Hungarian accent is so pronounced and to radio listeners’ surprising, that it causes Benny to ad-lib and Stanwyck to scream with utterly infectious laughter.

According to Herbert Spencer’s “The Physiology of Laughter” (1860), mankind (or, homo ridens) response in this way when expectations are suddenly disappointed and an excess of energy in our nervous system is discharged in the muscular reflex of laughing. It seems that, as an actress, Stanwyck expected Curtiz to have a great, controlling presence; instead, while to some extent in on it all, he became the hapless brunt of Benny’s jokes: “Between Hersholt and you, I don’t understand anything.” Perhaps, it is the kind of “sudden glory” Thomas Hobbes denounced as a “sign of pusillanimity.” But it sure feels good to salt this “Ham” with your own tears.

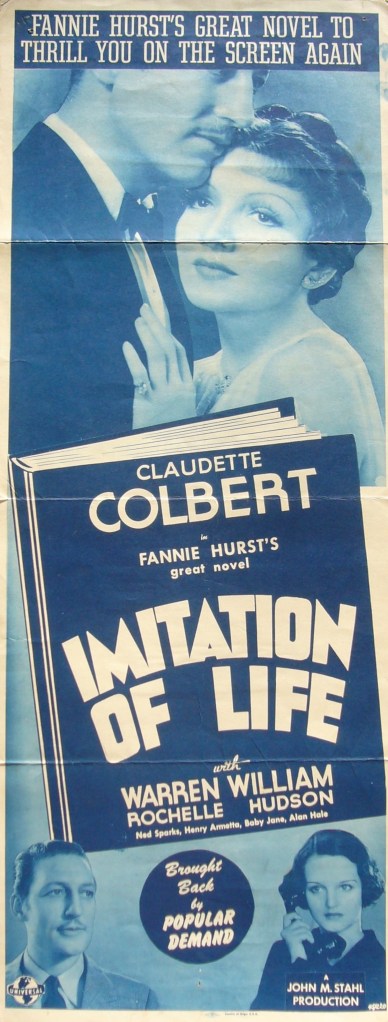

It wasn’t exactly a fresh cut. The sketch had already been presented once before (on 20 October 1940), with Benny trying the patience of Edward Arnold, Ernst Lubitsch, and Claudette Colbert. Yet Colbert appeared to have been too controlled an actress to let anything interfere with her live performance that evening; nor did Lubitsch’s accent trigger as many not altogether intentional laughs as that of his fellow director. It is Stanwyck’s reaction to Curtiz’s line readings (just hear him exclaim “stop interrupting”) and Benny’s extemporising to the occasion that makes “Ham for Sale” such an irreverent piece of Schadenfreude.

Relentless and immoderate, laughter here is a response to the “mechanical” (in Bergson’s sense), to the orderly and overly rehearsed—the minutely timed, predictable fare that so frequently went for on-air refreshment.

As usual, I am slow to catch up. A few years ago, the BBC relinquished the rights to televising the Oscars; and since we are not subscribing to the premium channel that does air them, I am relying on the old wireless to transport me to the events. So, here I am listening to …

As usual, I am slow to catch up. A few years ago, the BBC relinquished the rights to televising the Oscars; and since we are not subscribing to the premium channel that does air them, I am relying on the old wireless to transport me to the events. So, here I am listening to …  In the house I now call home, I am surrounded by a great many works of art, from oils and etchings to ceramics and stained glass. When I moved in the walls were already crowded with images; and I felt strangely if understandably disconnected from them and my new surroundings. For this simple reason, our Welsh cottage soon came alight each evening in the ersatz glow of moving images imported from the Hollywood of the 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s (a few exceptions notwithstanding). These pictures are projected onto a blind behind which unfolds the celebrated beauty of the Welsh landscape which, on a cloudless night, is more silver than the screen. For weeks after moving here from New York City (back in November 2004), a move worthy of a Daphne du Maurier thriller, were it not for my genial partner, I was unable to draw the blinds without bursting into tears, no matter how serene the scenery (our living room view being

In the house I now call home, I am surrounded by a great many works of art, from oils and etchings to ceramics and stained glass. When I moved in the walls were already crowded with images; and I felt strangely if understandably disconnected from them and my new surroundings. For this simple reason, our Welsh cottage soon came alight each evening in the ersatz glow of moving images imported from the Hollywood of the 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s (a few exceptions notwithstanding). These pictures are projected onto a blind behind which unfolds the celebrated beauty of the Welsh landscape which, on a cloudless night, is more silver than the screen. For weeks after moving here from New York City (back in November 2004), a move worthy of a Daphne du Maurier thriller, were it not for my genial partner, I was unable to draw the blinds without bursting into tears, no matter how serene the scenery (our living room view being  The smattering of rousing captions that accompany the images sure smacks of desperation. How do you sell a forgettable thriller as a must-see? You resort to words and phrases like “kill” and “cold blood, “evil” and “insane,” “murder” and “monstrous secret” to align the indifferent material you are pushing with the neo-gothic literature known to sell. In radio dramatics, no words were more prominent than “murder” and “death.” “Love” doesn’t sell half as well as death. “Sex” might, but radio was too cautions to go where most minds—and the species at large—are on a regular basis. To this date, US entertainment is more tolerant of mutilation than titillation, owing chiefly if indirectly to the violence that is religion.

The smattering of rousing captions that accompany the images sure smacks of desperation. How do you sell a forgettable thriller as a must-see? You resort to words and phrases like “kill” and “cold blood, “evil” and “insane,” “murder” and “monstrous secret” to align the indifferent material you are pushing with the neo-gothic literature known to sell. In radio dramatics, no words were more prominent than “murder” and “death.” “Love” doesn’t sell half as well as death. “Sex” might, but radio was too cautions to go where most minds—and the species at large—are on a regular basis. To this date, US entertainment is more tolerant of mutilation than titillation, owing chiefly if indirectly to the violence that is religion. Well, howdy. His handsome mug is before me whenever I grab a book from my shelves. Randolph Scott, Series two, Number 385 of Zuban’s

Well, howdy. His handsome mug is before me whenever I grab a book from my shelves. Randolph Scott, Series two, Number 385 of Zuban’s  Well, this being the anniversary of the birth of the man everyone including Cary Grant wanted to be, I decided to listen to a Lux Radio Theater production of

Well, this being the anniversary of the birth of the man everyone including Cary Grant wanted to be, I decided to listen to a Lux Radio Theater production of

Well, I have returned from New York and am off to London in the morning. In between, I celebrated Christmas in Wales. It was during this period of gift giving that I was presented with the fedora pictured here. Now, I am not one to don fedoras; nor am I a connoisseur of millinery craftsmanship. The giver is nonetheless someone intimately familiar with my fancies and foibles, someone who knows just how to press all the right soft spots. According to the certificate in the hatbox, the piece of felt in question, of Italian manufacture, was once in the personal collection of Claudette Colbert. Not in her heyday, mind you, but during the mid-1980s, about the time she appeared on stage in the revival of Aren’t We All? in London and New York.

Well, I have returned from New York and am off to London in the morning. In between, I celebrated Christmas in Wales. It was during this period of gift giving that I was presented with the fedora pictured here. Now, I am not one to don fedoras; nor am I a connoisseur of millinery craftsmanship. The giver is nonetheless someone intimately familiar with my fancies and foibles, someone who knows just how to press all the right soft spots. According to the certificate in the hatbox, the piece of felt in question, of Italian manufacture, was once in the personal collection of Claudette Colbert. Not in her heyday, mind you, but during the mid-1980s, about the time she appeared on stage in the revival of Aren’t We All? in London and New York.

It seems that the proverbial one who’s got more curves than the skeletons on the catwalks has not warbled her last. No, it ain’t over yet. According to my students, at least, whose rallying cries generated enough interest to keep my rather esoterically titled course “Writing for the Ear” alive, death warrants and prematurely issued certificates notwithstanding. The “fat lady,” of course, is the diva who gets to have the last word in opera. I don’t know where the expression originates; but it seems to be true for much of the operatic canon. Tonight, I am going to see Mimi expire in a production of La Bohème, performed by the Mid-Wales Opera Company.

It seems that the proverbial one who’s got more curves than the skeletons on the catwalks has not warbled her last. No, it ain’t over yet. According to my students, at least, whose rallying cries generated enough interest to keep my rather esoterically titled course “Writing for the Ear” alive, death warrants and prematurely issued certificates notwithstanding. The “fat lady,” of course, is the diva who gets to have the last word in opera. I don’t know where the expression originates; but it seems to be true for much of the operatic canon. Tonight, I am going to see Mimi expire in a production of La Bohème, performed by the Mid-Wales Opera Company.