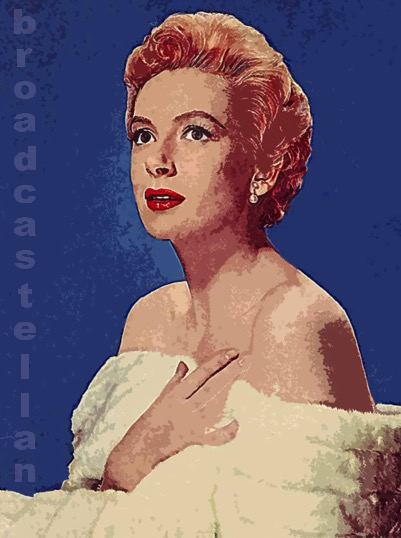

It was only two weeks ago that I celebrated her 86th birthday and caught up with her early career by watching Major Barbara (1941). Today, the world learned about the death of Deborah Kerr, who passed away on 16 October 2007 after a long illness. While her name is on everyone’s tongue, I am going to keep her voice in my ear, listening to some of her radio performances of the late 1940s and early to mid-1950s, a busy time in the life of the British actress gone Hollywood. “I just wasn’t destined to be a homebody,” Kerr told the readers of The Fan’s Own Film Annual back in 1960, providing her British audience with a glimpse of her peripatetic existence, her life in Hollywood, the challenges of ploughing “through the jungle on an adventurous safari” (for King Solomon’s Mines, shot in Africa), or going on a coast-to-coast tour (thirty-five weeks, forty cities) to play Laura Reynolds in Robert Anderson’s Tea and Sympathy, having starred in its successful Broadway run, which began on her 32nd birthday in 1953.

Yes, Kerr’s life was “one long round of packing luggage and then more or less living out of it for anywhere from four to fourteen months at a stretch.” Yet, through the wonders of the wireless, she still managed to enter the homes of millions of Americans who tuned to Jack Benny, the Screen Guild Theater, or the Hollywood Star Playhouse.

Now, I have never had the chance to see Kerr on stage, where she appeared, for instance, in a West End revival of Emlyn Williams’s The Corn Is Green, the film version of which (starring Bette Davis) I am going to catch at the Fflics film festival here in Aberystwyth next week. To me, radio, not film, is the next best thing to the theater. True, Kerr made her US radio debut at a time when live performances gave way to taped ones; but, even when its sounds are canned, radio still has the kind of intimacy not achieved on celluloid, no matter how small the image you are watching on your personal computer or television set.

Beginning in 1947, the year she moved from Britain to Hollywood, Kerr appeared on a number of popular or prestigious radio programs. Even though she is better known for starring in a film based on a sensational bestseller that, like few others, attacked the radio industry of the late 1940s, Frederic Wakeman’s previously mentioned The Hucksters, Kerr did go on the air, contaminated as it was, to promote her films and meet her audience.

In 1947, 1951 and 1952, she stepped onto the soundstage of the Lux Radio Theatre, starring in “Vacation from Marriage,” an adaptation of Alexander Korda’s Perfect Strangers, in which she had starred opposite Robert Donat back in 1945. For Lux, Kerr also reprised her roles in Edward, My Son (1949) and King Solomon’s Mines (1950).

As previously mentioned, Kerr played the title role in the NBC University Theater an adaptation of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (3 April 1949). She went on Tallulah Bankhead’s Big Show to recreate a scene from The Women (17 December 1950), and was heard on the long-running Suspense program in a thriller titled “The Lady Pamela” (31 March 1952).

Just what or who was “The Lady Pamela”? Not your Richardsonian heroine, to be sure. The name conjures Silver Spoon romances; but the spoons all end up in the lady’s pockets. Shamela’s more like it. Written by the prolific radio playwright Antony Ellis, the play opens as Pamela Barnes lays her eyes on a tiara, browsing in a New York antique shop that is promptly held up.

As it turns out, the “Lady” was in on the robbery. A tough, no-nonsense crook, she takes $500 out of the cut of her partner in crime for slapping her rather too realistically during the holdup. The police are soon on her case and “Lady Pamela” lands in the slammer; but the loot remains missing. Released nearly three years later, she returns to New York in search of the stolen goods and the guys who got away with it.

Always the “Lady,” the “first thing [she] did was to get [her] hair done,” to restore the old front. She meets a charming if hardly perfect stranger, one Mr. Wylie, who promises to assist her in finding her former collaborator—for a price:

Pamela: In other words, before you tell me where he is, I have to agree to help you kill him. Is that the idea?

Wylie: If you want your dough. That’s the idea.

Pamela: I want my dough, Mr. Wylie. Where is he?

“You’re quite a girl,” Wylie tells her, after she reveals to him that she was the mastermind behind the robbery. “And are you ‘quite a boy’?” she asks, before she slaps him, too. “You are much too emancipated,” she is told by the one who got away, now a “very top dog in black market,” whom she tracks down in London and confronts over cocktails. “I think I would have killed him there,” she confides in the audience, the play being written in the first person. “If I had had a gun, or a knife, I would have killed him.” Would she? You bet!

Billed as a “dramatic report,” “The Lady Pamela” is a sly playing against type for the generally dignified and often reserved Kerr, who gets her chance to play an American, rather than a British version, of a dame. It is Anna gone Warner Bros., a heroine stripping her period costumes and sipping her Long Island Ice Tea without sympathy. Only on the wireless, folks—Kerr like you’ve never seen her . . .