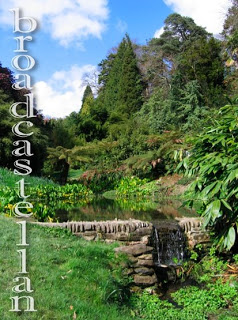

It was a crisp, bright afternoon in April when we visited Trebah Garden, one of the most beautiful spots in all of Cornwall. The sun had come out from behind a curtain of threatening clouds and the air was fragrant with a promissory note of summer that even the leafless, wintry trees in the distance were powerless to gainsay. As we walked down the sloping path, past the Rhododendron and Magnolias, beyond the dell of young Gunnera plants that, in time, would grow into a subtropical jungle, we reached a gate that led to a secluded beach. The sea was calm, peaceful the prospect; and even though the name of Trebah had been recorded in the Domesday Book, I felt far removed from the affairs of the world, present and past, as if sheltered in a reserve beyond the reach of history.

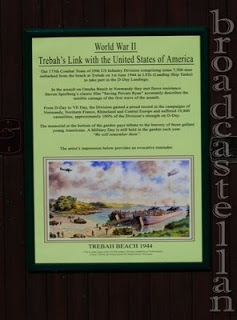

When I turned back toward the gate, that sense of detachment was shattered in an instant. I was reminded just how connected I was, even here, with the history of the world. I was yanked out of this perceived Eden by no uncertain notice of our fall: a sign telling me that, from it this secluded spot, thousands went into battle to secure the peace that I had enjoyed.

The memorial at Trebah tells of the 175th Combat Team of the 29th US Infantry Division, some 7,500 strong. On the 1st of June in 1944, those men embarked from that very beach to take part in the D-Day landings and, by carrying out their duty, face all but certain death.

“This is the hour,” Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote in her “Poem and Prayer for an Invading Army,” recited by Ronald Colman during a special radio broadcast on D-Day,

this is the appointed time.

The sound of the clock falls awful on our ears,

And the sound of the bells, their metal clang and chime,

Tolling, tolling,

For those about to die.

For we know well they will not all come home, to lie

In summer on the beaches.

And yet weep not, you mothers of young men, their wives,

Their sweethearts, all who love them well—

Fear not the tolling of the solemn bell:

It does not prophesy,

And it cannot foretell;

It only can record;

And it records today the passing of a most uncivil age,

Which had its elegance but lived too well,

And far, o, far too long;

And which, on History’s page,

Will be found guilty of injustice and grave wrong.

At Trebah Garden, where a Military Day is still being held each year, I was found guilty of the “grave wrong” it is to be walking in the splendor of oblivion. I shall not soon forget that sudden admonishment, that unsought clash by day.

Related recording

“Poem and Prayer for an Invading Army” (6 June 1944)