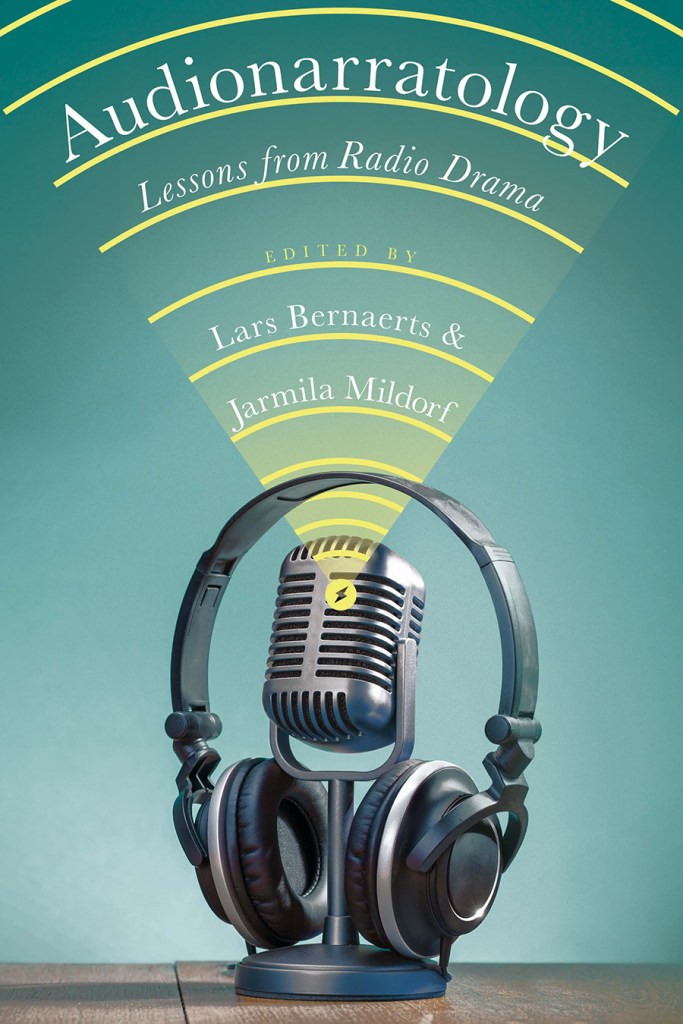

“Home at last,” I could almost hear myself sigh as, out of the narrow slit in our front door, I yanked the packet arriving today. Bearing my name, as few pieces of mail of any consequence or sustenance do nowadays, it contained the volume Audionarratology: Lessons from Radio Drama, to which I had been invited a few years ago to contribute a chapter. The book was published in July 2021 by Ohio State University, a press renowned for its contribution to the evolving discourse on narratology.

The titular neologism suggests that an engagement with aural storytelling is proposed as one way of broadening a field that has enriched the interpretation not only of literature but also of visual culture. Whether such aural storytelling should be subsumed under the rubric ‘radio drama’ is something I debated in my study Immaterial Culture, for which I settled on the term ‘radio play,’ as, I argued, the fictions written for radio production and transmission are hybrids whose potentialities remained underexplored and whose contribution to the arts underappreciated in part due to the alignment of such plays with works for stage and screen. Nor am I sure that, by adding the prefix, “audionarratology” will be regarded as a subgroup of narratology – which would defeat the purpose of broadening said field.

To the question what “Lessons” may be learned from plays for radio, or from our playing with them, the quotation that serves as title of my essay provides a serviceable response: “There ain’t no sense to nothin.” The line is uttered by one of the characters in I Love a Mystery, the thriller serial I discuss – and it is expressive of the bewilderment I felt when first I entered the world created in the 1930s and 1940s by the US American playwright-producer Carlton E. Morse. My cumbersome subtitle is meant to suggest how I responded to the task of making sense not only of the play but also of the field in which I was asked to position it: “Serial Storytelling, Radio-Consciousness and the Gothic of Audition.”

By labelling ‘gothic’ not simply the play but my experience of it, I aim to bring to academic discourse my feeling of unease, a sense of misgivings about explaining away what drew me in to begin with, the lack of vocabulary with which adequately to describe my experience of listening, the anxiety of having to theorise within the uncertain boundaries of a discourse that I sought to broaden instead of delimiting.

Throughout my experience with radio plays of the so-called golden age, I felt that, playing recording or streaming play, I had to audition belatedly for a position of listener but that I could never hear the plays as they were intended to be taken in – serially, via radio – during those days before the supremacy of television, the medium that shaped my childhood.

In the essay, I try to communicate what it feels like not knowing – not knowing the solution to a mystery, not quite knowing my place vis-à-vis the culture in which the play was produced or the research culture in which thriller programs such as I Love a Mystery are subjected to some theory and much neglect. Instead of analysing a play, I ended up examining myself as a queer, English-as-second-language listener estranged from radio and alien to the everyday of my grandparent’s generation – never mind that my German grandfather fought on the Axis side while the US home front stayed tuned to news from the frontlines as much as it tuned in to thrillers and comedies that were hardly considered worthy of being paraded as the so-called forefront of modernism. So, a measure of guilt enters into the mix of emotions with which I struggle to approach or sell such cultural products academically.

The resulting chapter is proposed as a muddle, not as a model – although its self-consciousness may be an encouragement to some who are struggling to straddle the line between their searching, uncertain selves and the construct of a scholarly identity. Its failings and idiosyncrasies are no strategic efforts to fit in by playing the misfit or refitting the scene – they are proposed as candid reflection of my mystification.

They also bespeak the fact that the essay, unfinished or not fully realised though it may seem, was a quarter century in the making. It started out by twisting the dial of my stereo receiver and happening on Max Schmid’s ear-opening program The Golden Age of Radio on WBAI, New York, agonising whether to turn my newly discovered hobby into the subject of academic study, enrolling in David H. Richter’s course “The Rise of the Gothic” at CUNY, and by responding to the essay brief by exploring gothic radio plays and radio adaptations of Gothic literature.

Once I had decided to abandon my Victorian studies in favor of old-time radio, the essay was revised to become a chapter of my PhD study Etherized Victorians. It was revisited but removed from Immaterial Culture as an outlier – the only longer reading of a play not based on a published script – during the process of negotiating the space allotted by the publisher. It had a lingering if non-too-visible presence on my online journal broadcastellan as an experiment in interactive blogging, and it now appears in a volume devoted to a subject of which I had no concept when I started out all those years ago.

The draft, too, has gone through a long process of negotiation — of editing, cutting and rewriting – at some point of which the frankness of declaring myself to be among the “outsiders” of the discourse did not make the editors’ cut.

So, home the essay has come; but the home has changed, as has its dweller, a student of literature who transmogrified into an art historian with a sideline of aurality, and who now has to contend with tinnitus and hearing loss when listening out for clues to non-visual mysteries and, ever self-conscious, waits for his cue to account for the latest of his botches, or, worse still, to be met with silence. Estrangement, uncertainty, and the misery of having to account for the state of being mesmerised by mysteries unsolved – such is the gothic of audition.

Nearly two centuries ago, young Rebecca Sharp marked her entrance into the world by hurling a book out of a coach window. That book, reluctantly gifted to her by the proprietress of Miss Pinkerton’s academy for young ladies, was Johnson’s dictionary, a volume for which Ms. Sharp had little use, given that she was rarely at a loss for words. By the time her story became known, in 1847, words in print had become a rather less precious commodity, especially after the British stamp tax was abolished in 1835, which, in turn, made the emergence of the penny press possible. Publications were becoming more frequent—and decidedly more frivolous.

Nearly two centuries ago, young Rebecca Sharp marked her entrance into the world by hurling a book out of a coach window. That book, reluctantly gifted to her by the proprietress of Miss Pinkerton’s academy for young ladies, was Johnson’s dictionary, a volume for which Ms. Sharp had little use, given that she was rarely at a loss for words. By the time her story became known, in 1847, words in print had become a rather less precious commodity, especially after the British stamp tax was abolished in 1835, which, in turn, made the emergence of the penny press possible. Publications were becoming more frequent—and decidedly more frivolous.

The currency market has been giving me a headache. The British pound is anything but sterling these days, which, along with our impending move and the renovation project it entails, is making a visit to the old neighborhood seem more like a pipe dream to me. The old neighborhood, after all, is some three thousand miles away, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan; and even though I have come to like life here in Wales, New York is often on my mind. You don’t have to be an inveterate penny-pincher to be feeling the pressure of the economic squeeze. I wonder just how many dreams are being deferred for lack of funding, dreams far greater than the wants and desires that preoccupy those who, like me, are hardly in dire straits.

The currency market has been giving me a headache. The British pound is anything but sterling these days, which, along with our impending move and the renovation project it entails, is making a visit to the old neighborhood seem more like a pipe dream to me. The old neighborhood, after all, is some three thousand miles away, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan; and even though I have come to like life here in Wales, New York is often on my mind. You don’t have to be an inveterate penny-pincher to be feeling the pressure of the economic squeeze. I wonder just how many dreams are being deferred for lack of funding, dreams far greater than the wants and desires that preoccupy those who, like me, are hardly in dire straits.

Well, it kept Bing Crosby on the air; but it also made that air feel a lot staler. Magnetic tape. Its introduction back in 1946 was a recorded death sentence to the miracle and the madness of live radio. Dreaded by producers of minutely timed dramas and comedy programs, going live had been the life or radio. Intimate and immediate, each half-hour behind the microphone had the urgency of a once-in-a-lifetime event. Actors and musicians gathered for a special moment and remained in the presence of the listener for the express purpose of being there for them and with them, however far away. They made time for an audience that, in turn, was making time for them. In a world of commerce in which democratic principles were reduced to the ready access to cheap reproductions, the quality of being inimitable and original was fast becoming a rare commodity indeed. The time for the magic of the time-bound art, the theater of the fourth dimension, was fast running out.

Well, it kept Bing Crosby on the air; but it also made that air feel a lot staler. Magnetic tape. Its introduction back in 1946 was a recorded death sentence to the miracle and the madness of live radio. Dreaded by producers of minutely timed dramas and comedy programs, going live had been the life or radio. Intimate and immediate, each half-hour behind the microphone had the urgency of a once-in-a-lifetime event. Actors and musicians gathered for a special moment and remained in the presence of the listener for the express purpose of being there for them and with them, however far away. They made time for an audience that, in turn, was making time for them. In a world of commerce in which democratic principles were reduced to the ready access to cheap reproductions, the quality of being inimitable and original was fast becoming a rare commodity indeed. The time for the magic of the time-bound art, the theater of the fourth dimension, was fast running out.